Position

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP):

- recognises climate change as a key public health issue1,2

- commits to mitigation and adaptation strategies as an organisation and promoting and advocating for these among general practitioners (GPs), healthcare organisations and the community

- advocates for policies to protect human health from risks of climate change at local, state, national and international government levels

- considers it important for GPs to understand and communicate the causes, health risks and consequences of climate change as well as mitigating actions and adaptation to climate change at individual and population levels

- emphasises the importance of general practice research to inform RACGP and GP responses to climate change and its impact on human health.

Background

Climate change resulting from human activity is affecting our relationship with our environment and presents an urgent, significant and growing threat to health worldwide.1 Activities such as burning fossil fuels for energy and changes in land use, particularly deforestation, increase the levels of carbon dioxide and other gases in the atmosphere, holding heat near the surface of the earth. Increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and the resulting increased heat, are altering planetary systems, including ocean circulation, prevailing winds and cloud cover.1 Increased carbon dioxide is considered the largest single contributor to human-induced climate change.3

Climate change affects human health directly, indirectly and through societal responses. An example of direct climate change impact is the increase in morbidity and mortality resulting from higher temperatures and heatwaves, particularly among vulnerable groups such as elderly people and those with pre-existing cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.1 The indirect impacts of climate change result from interactions of climate with other systems. Examples include declining agricultural yields and quality caused by drought, resulting in poorer nutrition despite higher caloric intake; and changes in the distribution of vectors that spread infectious disease, caused by flooding.1 Socially mediated impacts of climate change may include conflict, migration, and damage to livelihood from droughts or cyclones.1

Vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, both in Australia and globally, depends on geographic, social, economic and biological factors. Overall, climate change will increase inequality, as people with fewer material, social and health resources will be more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change.

Projected changes in Australia’s climate that affect health include:

- more frequent and widespread heatwaves and extreme heat, increasing the risks of heat stress, heat stroke, dehydration and mortality.4 Heatwaves contribute to acute cerebrovascular accidents, and aggravate chronic respiratory, cardiac and kidney conditions and psychiatric illness. The current carbon dioxide emissions trajectory is projected to increase heatwave-related deaths threefold in Melbourne and Brisbane and fivefold in Sydney over the period 2013 to 2080, compared with current heat-related mortality5

- more frequent, severe and widespread bushfires, increasing risks of burns, smoke inhalation, heat stress, dehydration, trauma and long-term mental health impacts6

- more extreme rainfall events, flooding and storm surges, increasing risks of injury, communicable disease transmission, distress, and acute and chronic anxiety disorders7

- more frequent, prolonged and widespread droughts, a significant cause of adverse mental health among rural Australians.7

The role of GPs

GPs have key roles in identifying, reducing and managing adverse health effects of climate change on Australians and the international community, within each of the domains of general practice.

1. Communication skills and the doctor–patient relationship

- Identifying patients who are particularly vulnerable to heat, and ensuring that they take precautions and are monitored4

- Ensuring that patients and the local community have access to and respond to public health advice, such as disaster and weather warnings from health departments and emergency services4

- Recognising that climate change exacerbates health inequities – for example, through the unequal impacts of extreme weather events – and seeking opportunities to promote health and social equality1

2. Applied professional knowledge and skills

- Promoting urgent action to mitigate climate change through individual, practice-based, social and population-based initiatives8

- Identifying co-benefits of action to reduce climate change in clinical consultations – for example, encouraging active transport, promoting low-energy diets including less meat and processed food consumption, preventing unwanted pregnancy,9,10 and promoting energy-efficient homes and buildings8

3. Population health and the context of general practice

- Leading the response to the burden of non-communicable diseases that are the main cause of morbidity and mortality in Australia today, such as mental illness

- Undertaking and supporting ongoing education for themselves, other health professionals, patients and the wider community about climate change and its impact on individual and population health

4. Professional and ethical role

- Taking personal action to mitigate climate change and improve health and equity. Examples of actions with both health and climate benefits include using active transport, minimising air travel, reducing highly processed food consumption, reducing meat consumption, and encouraging use of smaller cars driven less often8

- Supporting community action – for example, community gardens for local food production, public open space for outdoor recreation and physical activity, safe walking and cycle ways, high-quality public transport systems8

- Working with other professionals to strengthen individual, community and social action, through government, business and community organisations

- Using general practice expertise and GPs’ professional position as trusted community leaders to advocate on behalf of patients for effective climate change policy and action8

5. Organisational and legal dimensions

- • Investigating opportunities to reduce energy usage and other environmental impacts, minimising waste, improving efficiency, investing savings in further energy reductions11 and addressing opportunities for new technologies2,8

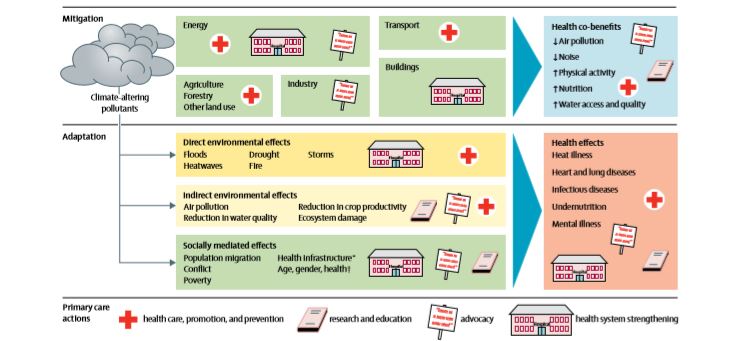

While the impact of each change is small, action by GPs as a trusted group of leaders is important for modelling, education and facilitation of community-wide action. Figure 1 provides a framework for primary care to improve health by mitigation and adaptation to climate change.8

Related RACGP resources

Managing pandemics

Managing emergencies in general practice: A guide for preparation, response and recovery

- Parise I. A brief review of global climate change and the public health consequences. Aust J Gen Pract 2018;47(7):451–56.

- Council of Presidents of Medical Colleges. Managing and responding to climate risks in healthcare. Deakin, ACT: CPMC, 2018. Available at [Accessed 28 August 2018].

- NSW Government, Office of Environment and Heritage. Causes of climate change. Sydney South, NSW: NSW Government, Office of Environment and Heritage, [date unknown]. [Accessed 29 March 2019].

- Wilson L, Black D, Veitch C. Heatwaves and the elderly: The role of the GP in reducing morbidity. Aust Fam Physician 2011;40(6):637–40.

- Guo Y, Gasparrini A, Li S, et al. Quantifying excess deaths related to heatwaves under climate change scenarios: A multicountry time series modelling study. PLoS Med 2018;15(7):e1002629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002629.

- Johnston FH. Bushfires and human health in a changing environment. Aust Fam Physician 2009;38(9):720–24.

- Ng FY, Wilson LA, Veitch C. Climate adversity and resilience: The voice of rural Australia. Rural Remote Health 2015;15(4):3071.

- Xie E, de Barros EF, Abelsohn A, Stein AT, Haines A. Challenges and opportunities in planetary health for primary care providers. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2(5):e185–87. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30055-X.

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2008;39(1):18–38.

- Campbell-Lendrum D, Lusti-Narasimhan M. Taking the heat out of the population and climate debate. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2009;87(11):807. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072652.

- McGain F, Naylor C. Environmental sustainability in hospitals – A systematic review and research agenda. J Health Serv Res Policy 2014;19(4):245–52. doi: 10.1177/1355819614534836.