Domestic violence, also known as intimate partner violence, damages the social and economic fabric of communities, and the mental and physical health of individual women, children, adolescents and men. Global guidelines and Australian policy have prioritised the reduction of the impact from domestic violence, especially on children, and has identified the crucial role of an effective health system in achieving this goal.1,2

Most women who experience domestic violence seek help at some point from general practice.3 Estimates are that every week, a general practitioner (GP) sees up to five women who have been abused by their partners, of which the GP may not be aware.4 One in 10 women attending general practice have been afraid of their partners in the previous 12 months, and one in three women have experienced fear of a partner over their lifetime.5 An Australian trial found that training GPs to deliver brief counselling to women identified through intimate partner violence screening improved depressive symptoms, while a UK general practice intervention to identify and refer found that training GPs resulted in increased referral to domestic violence services.6,7

GPs also see men, either alone or as part of the whole family, and so are well placed to provide an appropriate first-line response for men who use, or who are at risk of using, violence in their relationships.8 This could include briefly assessing family safety and needs, and providing access to resources and referrals. It is very important that if GPs suspect that men are using violence, that women and children have support and access to safety planning from specialist domestic violence services.

Similarly to women, men also see the family doctor as a source of support.9 Despite this, very little training is provided to GPs to work with men who use violence. While services and support for women and children who experience domestic violence are a priority, policy and guidelines suggest they need to be underpinned by intervention strategies that directly target men who use violence, and support them to stop offending as early as possible.1,8

There are community norms and expectations that underlie men’s use of violence to maintain power and control over their partner or ex-partner. Research has linked domestic violence to societal acceptance of male dominance, stereotyping of gender roles, and the normalisation of violence as a way to resolve conflict.10 Poverty and unemployment are also risk factors for perpetration of domestic violence. However, perpetration also occurs across the socioeconomic spectrum.

How can GPs identify perpetrators?

To identify men who use violence, GPs need to be constantly on the lookout. To quote Thomas McCrae from Jefferson Medical College: ‘more mistakes are made by not looking than not knowing’. There is often no distinguishing characteristic of a man who will be violent towards his partner.8 GPs need to be aware that men tend to minimise responsibility for their violence, blame the victim or other external factors, and greatly under-report their use of violence.8 They will generally have developed ways of convincing themselves and others that they are not responsible for their violence, and can invite GPs to collude with their attitudes and beliefs.8 Mental health issues or substance abuse problems can also be linked to domestic violence, although many perpetrators do not experience these problems. GPs need an index of suspicion of the possibility of abuse among this cohort.11,12 At the same time, it is also important not to over-pathologise men who use violence. If a GP sees a man they suspect may be using violence, then the use of funnelling questions from a broad subject to more specific is recommended (Box 1).13,14

Box 1. Questions to ask men about domestic violence if there are clinical indicators

|

- How are things at home?

- How is your relationship? What are the best and worst aspects of it?

- Can you give me a specific example?

- What happens when you argue? Do you get angry? What do you do when you get angry?

- I need to ask some direct questions about these issues. Is that okay?

- When did you first get worried about how you deal with anger?

- Do you think she is ever scared/frightened/intimidated by you?

- Have you ever done something that you have later regretted?

- Tell me about some other times when you have gone too far. How often does this happen?

- How do you get physical with your partner when arguing? Let’s consider a particular time. What did you do next? On a scale of 1 to 5, how loudly/hard were you shouting/hitting?

- What is the worst thing you have done to your partner? Have you or your partner ever been injured? Have the police ever been called?

- If there was a fly on the wall in your home, when you feel angry, what would that fly be seeing about your behaviour?

|

Management role of GPs

There are three main roles of the GP in intervening early with men who use violence in their relationships:8,15

- briefly assess men

- prepare them to accept a referral to a men’s behaviour change program

- undertake alternative interventions to decrease the risk of violence if a referral is not taken up.

The GP’s role at this early stage is trying to engage the part of the man that wants a better life or cares about his children. A stance of neutrality, somewhere between colluding and accusatory, is generally likely to be more constructive.15

It is hard for GPs to think of some of their patients as ‘perpetrators’, and they may worry that addressing this issue will damage their relationship. However, GPs need to be open to identifying and providing support to men to enable successful intervention.16 Iwi and Newman outline the importance of building a therapeutic alliance while tackling denial and minimisation.15 The steps include assisting men to extend the definition of violence and abuse to include emotional and sexual abuse, and using their children as a means to abuse their partner. This should be followed by an initial safety assessment of the man’s partner and their children through taking a history of his violent behaviours and other factors (Box 2). Men who use violence in their relationships are more likely to have grown up in families where their father or stepfather was violent, or where they experienced child abuse or another adverse childhood experience.17 Mental disorders and substance abuse may result in more significant risk of injury to the victim.18,19

Box 2. Risk indicators of ongoing domestic violence26

|

- The man’s history of violent behaviour both within and outside the household

- The man’s access to weapons

- Recent separation or divorce

- Stressors such as unemployment or recent bereavement

- History of witnessing or being the victim of family violence as a child

- Evidence of mental health problems or personality disorder in the man

- Resistance to change and lack of motivation for treatment

- Attitudes of the man that support violence towards women

|

Not all of the aforementioned risk factors need to be present for family safety to be compromised. GPs can phone a service (eg Men’s Referral Service) to obtain a quick secondary consultation about what to do in a particular situation when they are worried about safety issues or how to motivate a man to attend a program. If GPs have safety concerns, they should make a referral, if possible, to expert domestic violence services and/or child protection agencies. All GPs need to be aware of mandatory reporting requirements for child abuse, which vary across Australia (see Chapter 6 of The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ [RACGP’s] Abuse and violence – Working with our patients in general practice at www.racgp.org.au/whitebook).

The RACGP also recommends that GPs notify the police if the victim has serious injuries (eg broken bones, stab wounds, lacerations or gunshot wounds).8,20 In Australia, only the Northern Territory has mandatory reporting for any adult who reasonably believes another person is at risk of, or is experiencing, serious physical harm through domestic violence.21

It can be helpful to concentrate on analysing an incident of abuse and working on the impact of the man’s actions, especially on children (Box 3). After taking a history, motivational interviewing techniques may be used (eg exploring the costs/benefits of continuing his abuse versus the costs/benefits of changing and stopping his abuse). These approaches draw on feminist models and motivational interviewing techniques to engage men in accepting a referral.8,22

Box 3. Questions to ask in the context of fathering and domestic violence15

|

- How did you hope being a father would be?

- How would you like your children to think of you in 10 or 20 years’ time? If I were to interview them in 10 or 20 years, what would you hope they would say about you?

- What’s working well? What are the hardest times for you?

- How do your children react when you get angry? What do you think they are aware of?

- Have they seen any violence? What effect do you think that had?

- Do you regret what happened recently?

- What were things like between your parents? What effect did that have on you?

- How do you want to be as a partner and a father?

- How do you feel about coming back and seeing me again, and we can work out a place for you to go to get help with this?

|

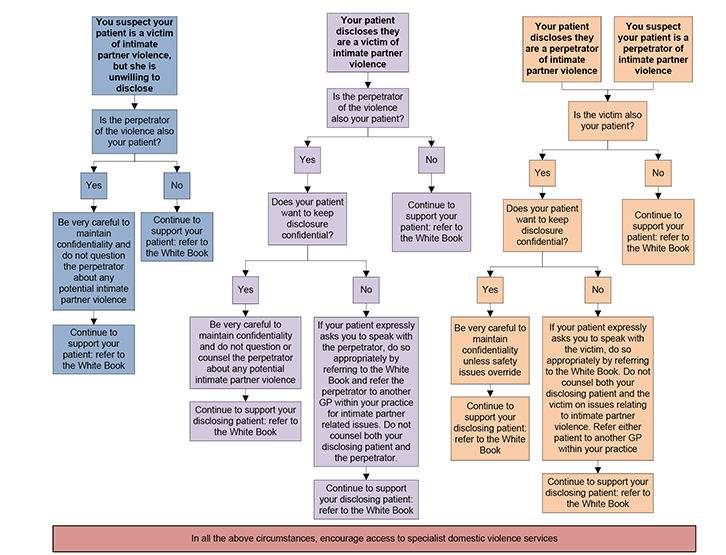

It is not recommended that one GP counsel both the woman and the man about domestic violence.23 However, in a situation where the woman or the man have not disclosed the abuse, it may be necessary for GPs to continue to see both partners for ongoing medical care. Complexity and confidentiality issues around one GP seeing the whole family may be managed in several ways (Figure 1). Where there is not an immediate high risk, we outline some recommendations below.

|

| Figure 1. Seeing the whole family |

If only the woman has disclosed domestic violence, but does not want the man to know she has disclosed, the GP could offer the woman referral to a colleague within the practice and a domestic violence service. The GP must ensure confidentiality by not letting the man know that his partner has disclosed. This is to ensure the safety of the woman and her children.

If only the man has disclosed domestic violence, but does not want the woman to know he has disclosed, there may be a role for the GP to discuss this issue with a GP colleague and refer either the male or female patient within the practice. This will allow sharing of information relevant to the whole family across the practice to further assess safety and risk.

If both the woman and man have disclosed domestic violence, the GP can choose to refer one of them to an alternative GP within the practice. In cases where this is not possible or appropriate (eg rural or remote areas), the GP can choose to refer to services nearby, where available. The GP could state that the RACGP does not advise counselling or seeing both partners when the man is using violence in a relationship.8 Choosing which patient to keep will always be a difficult decision, but the GP will usually have seen more of one patient than the other.

Different GPs are recommended because there is a danger of inadvertently revealing some of the information provided by the woman to the man. Many men who use violence in their relationships can be attuned to what they think the woman might be telling others.8 If the GP accidentally relays something she has said, the man may retaliate against her. Men can also be persuasive in minimising, denying or justifying their violence while using techniques to absolve responsibility for their behaviour and blame the woman.8 It is important for a different GP to hear the woman’s story, so as not to be influenced if the man is using minimising narratives.

Men who use violence in their relationships do so when they are both angry and calm, often using controlling tactics.8 In addition, most men who use such violence choose not to use violence in other settings (eg the workplace or if there is someone else present). The man can be asked:

When you were violent/abusive to your partner, what difference would it have made if your boss/best friend/the police happened to be in the room at the time? Would you have behaved in the same way or would you have modified your behaviour?

Many men will try to direct the conversation back to blaming their partner (eg ‘You don’t live with her, she keeps screaming at me, and is hopeless with finances …’). It is important not to allow an ongoing rehearsal of these narratives and to assertively yet calmly bring the attention back to him:

Let’s focus on how you responded. The only person you can change is you. So let’s think together about what you did and how you would like to handle it differently next time. Would you like to do that?

In summary, management objectives include:8

- assessing and taking a history – especially suicidality, substance abuse, mental health, any adverse childhood experiences, weapon ownership

- conveying that abuse and violence are not okay – condemn the actions, not the person

- enhancing safety of women and children

- encouraging a change in attitudes – help the man take responsibility and encourage active uptake of referrals.

Referrals

Men’s behaviour change programs are the referral option of choice, even with men who have substance abuse or mental health issues, although more research into interventions for men is still needed.24 These programs are not anger management programs and come from a gender-based perspective that conceptualises violence as a choice on the basis of male power and privilege. The programs involve pointing out the pros and cons of violence, deconstructing attitudes and beliefs that promote men’s violence, and anger management techniques to promote alternatives to violence.25 If the substance abuse or mental health issues are urgent, or if the man is not ready to accept a referral to a men’s behaviour change program, then a referral to a drug/alcohol rehabilitation and/or mental health service is certainly better than no referral at all.

Box 4. Key national services for men

|

|

|

In most Australian states, there are telephone information, referral and counselling services for men who use violence. These services can assist GPs in locating men’s behaviour change programs and provide information and resources. Men who do not appear ready to attend a program (Table 1) might be more comfortable taking the initial step of calling a service themselves, and the service will then attempt to further motivate them to attend a program. The RACGP has provided an extensive list of resources available for men and the family, but the key national services for men are listed in Box 4. Following up and supporting the man’s acceptance of a referral and monitoring the safety of the family is an ongoing task. It is also very important that GPs do the best possible to ensure that the woman is receiving counselling and support from a specialist domestic violence service.

Table 1. Readiness to accept referral, based on stage of change5,27

|

| Stage | Description | Suggested response |

|---|

| Pre-contemplative |

The man is not aware that he has a problem or holds a strong belief that it is his partner’s fault and does not wish to accept a referral |

Respond neutrally, encouraging the man to look at his own behaviour/actions rather than focusing on what the partner is doing. Suggest regular appointments to talk through issues and discuss what a ‘healthy relationship’ might look like. Provide program lists |

| Contemplation |

The man has identified a problem but remains ambivalent about whether or not he wants to or is able to accept a referral |

Try to identify possible catalysts for accepting referral (eg children). Work with the man to identify what sort of partner/father he would like to be and suggest that there might be ways he could achieve this with support from Men’s Referral Service |

| Preparation/decision |

Some catalyst for accepting referral has arisen (eg concern for children, realisation that partner might leave him) |

Directly assist contacting Men’s Referral Service to get more information about available programs in the man’s local area |

| Action |

Referral is accepted to attend a men’s behaviour change program, or alcohol, drug or mental health service |

Support and validate the man’s positive action in accepting the referral |

| Maintenance |

Commitment to attending program is sustained |

Support and validate the man’s positive actions towards change. Check in regularly to ensure that the man is ‘on track’ |

| Returning/relapsing |

The man may feel compelled to stop attending the program. Reasons may include finding life too stressful, no access to children or resources |

Explore alternative referral options. Remind the man of all the positive changes he has achieved (eg better relationship with children) |

Key points

- Domestic violence encompasses physical, emotional, economic and sexual violence and abuse of a partner.

- Domestic violence is common in general practice, with estimates that one in 10 men who use violence in their relationships attend a clinic.

- GPs are well positioned to recognise, ask, respond to and appropriately refer men who are using violence. GPs should have a higher suspicion with men experiencing mental health and/or substance abuse issues.

- Immediate safety of the partner and any children should be the predominant concern for a GP when a man who uses domestic violence is identified.

- For domestic violence issues, it is not recommended for one GP to counsel both the woman and the man about their relationship.

- Men’s behaviour change programs are the referral options of choice for men who perpetrate domestic violence.

Authors

Kelsey Hegarty MBBS, FRACGP, DRANZCOG, PhD, Professor and Director of Researching Abuse & Violence (RAVE) Programme, Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC. k.hegarty@unimelb.edu.au

Kirsty Forsdike-Young BA (Hons), PgDipLaw, PgDipLegalPractice, Senior Research Officer and Programme Coordinator, Researching Abuse & Violence (RAVE), Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC

Laura Tarzia BCA, PGradDipArts (Socio), GradDipArts (Socio), PhD, Research Fellow and Deputy Lead of Researching Abuse & Violence (RAVE) Programme, Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC

Ronald Schweitzer MBBS, FRACGP, General Practitioner, East Bentleigh Medical Group, East Bentleigh, and Lecturer, Monash University, VIC

Rodney Vlais BPsych, MPsych, Associate Chief Executive Officer, No To Violence and Men’s Referral Service, Burnley North, VIC

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.