Case

In October 2015, a woman, 24 years of age and with two children, had a Mirena intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) inserted under general anaesthetic immediately post-termination of pregnancy. She noted in the following month that the IUCD strings seemed too long (‘the length of a finger’). She was otherwise well, with no other significant medical or family history.

In December 2015, her IUCD was spontaneously expelled. She was due to go on holiday and did not have time to see a doctor so, believing the IUCD would be easy to re-insert, she asked a friend to help her put the IUCD back. She cut the strings herself to make it easier for re-insertion. To assist her friend in the procedure, she held her vagina open with two spoons (approximating a speculum) and directed her friend to push the IUCD into the cervix. She recalls the procedure being painful at the time, but ‘not too bad’. She continued to have periods and did not have any further pain.

In February 2016, she attended our medical centre for a routine screen for sexually transmissible infections (STIs). When she related the story of her IUCD expulsion and re-insertion, the doctor examined her and could not see any strings at the cervical os. A pelvic ultrasound was ordered, even though she described cutting the strings off herself. She declined additional contraception at this consultation because she was sure the IUCD was in the right place.

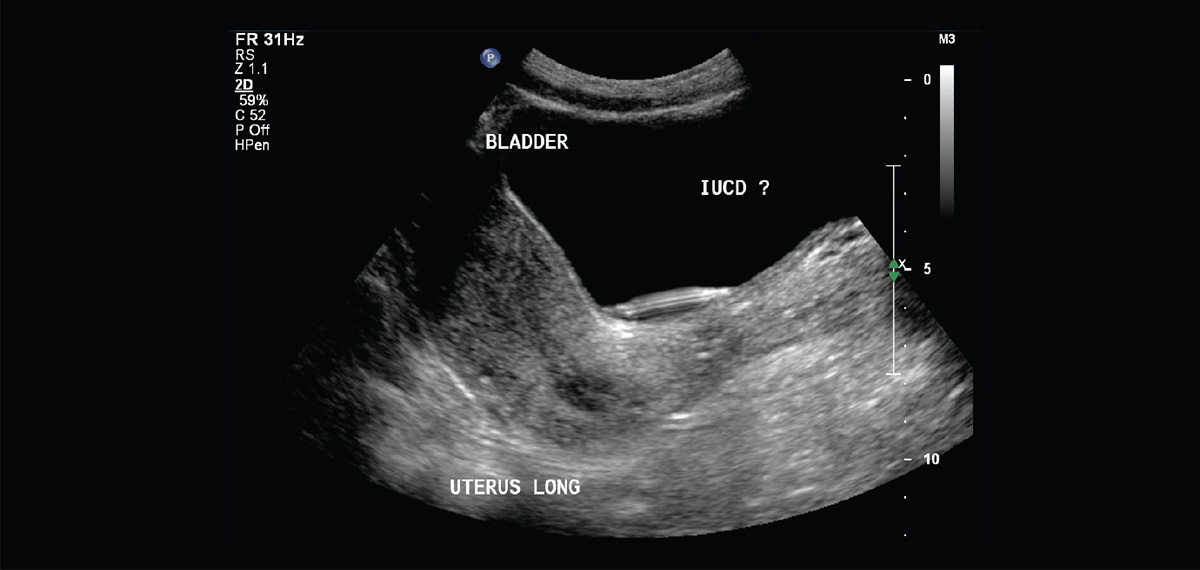

In May 2016, she presented with symptoms consistent with cystitis (Escherichia coli was cultured from the urine) and it was noted that the ultrasound had not been performed. She was treated with trimethoprim 300 mg daily for five days and her symptoms completely resolved. She was again encouraged to have a pelvic ultrasound to locate her IUCD. However, because of her continued busyness and belief that her IUCD was in the right place, the ultrasound was not performed until June 2016. The pelvic ultrasound report showed an IUCD in the bladder with no air in the bladder to indicate a vesicovaginal fistula (Figure 1). She was started on the contraceptive pill while awaiting removal of the intravesical IUCD and insertion of a new IUCD.

Figure 1. Pelvic ultrasound showing the IUCD within the bladder cavity

On referral to a gynaecologist, a further two ultrasound scans were obtained to confirm the IUCD placement. In December 2016, the intravesical IUCD was removed and replaced with a new IUCD in her uterus. In the months leading up to the IUCD removal, the patient continued to have multiple episodes of cystitis and two non-viable pregnancies, as she had stopped her oral contraceptive pill.

Question 1

What should you do if IUCD threads are not visible in the vagina?

Question 2

How common is IUCD expulsion?

Question 3

How did the patient’s IUCD get into her bladder?

Question 4

What are the issues with an intravesical IUCD?

Answer 1

Expulsion, perforation or pregnancy are possible reasons for IUCD threads not being visible in the vagina, although, a common cause may just be the retraction of the threads into the uterus or cervical canal. Pregnancy should first be excluded – conducting a urine pregnancy test is the quickest way to do so. If the woman is not pregnant, advise an alternative method of contraception and arrange for a pelvic ultrasound scan. If the ultrasound confirms that the IUCD is in the uterus, the woman will be receiving the full contraceptive effect and the IUCD may be left in situ until the time for removal (ie using a thread retriever, long forceps, hysteroscopy). If the ultrasound confirms that the IUCD is not in the uterus, request abdominal and pelvic X-rays to locate the IUCD. If the entire abdominal cavity and pelvis are visualised with no IUCD located, this confirms expulsion and need for IUCD re-insertion or an alternative method of contraception. If an IUCD is seen on the abdominal or pelvic X-ray, this may indicate perforation and the patient would need elective laparoscopic removal. A helpful flowchart is available at the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare website.1

Answer 2

The IUCD is a safe and cost-effective, long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC),2 and can reduce rates of unintended pregnancy.3 However, spontaneous expulsion of IUCDs can occur in 3–5% of women, usually within the first three months of insertion.2 Factors that may increase this risk of expulsion include being an adolescent, previous expulsion, obesity, heavy menstrual bleeding or post-abortion placement.2

Answer 3

Mirena has a soft and flexible plastic frame that is very difficult, if not impossible, to push through the vaginal or uterine cervix muscle wall, and then through the bladder wall. Uterine perforation usually occurs at insertion, following the tract made by the metal sound and subsequent intravesical migration.4 We present this rare case of an IUCD in the bladder due to self-insertion through the urethra, not because of uterine perforation with intravesical migration. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an IUCD that was self-inserted into the bladder. When reviewed, the patient expressed surprise that the IUCD could have been pushed into her urethra. She thought that the opening to aim for would have been obvious to her friend, and that her friend could not have missed ‘the big lump’ (ie cervix). This case highlights a potential knowledge gap for some women in their understanding of perineal anatomy.

Answer 4

An intravesical IUCD may not necessarily be symptomatic. In our case report, the patient was asymptomatic for six months. It is important that an intravesical IUCD be removed because of the reported complication of secondary calculus formation.5 This can present with cystitis, haematuria and pelvic pain.6 The patient had two non-viable pregnancies while waiting for the removal of her intravesical IUCD, demonstrating the lack of contraceptive effect when the IUCD was in the bladder. This emphasises the lack of local effects of an IUCD if it is not in direct contact with the endometrium, and the importance of arranging an alternative method of contraception until the IUCD is replaced.

Key points

- If IUCD strings are not present, it is imperative to confirm the location of the IUCD.

- Arrange for an alternative method of contraception to be used until the IUCD is confirmed to be in the correct place.

- An intravesical IUCD in the bladder provides no contraceptive effect.

- While there are reports of intravesical IUCDs due to uterine perforation during insertion, a self-inserted intravesical IUCD is also possible.

Authors

Jason J Ong PhD, MMed, MBBS, FRACGP, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic. jong@mshc.org.au

Helen Henzell MBBS, Sexual Health Physician, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic

Lisa Doyle MBBS, General Practice Registrar, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic

Christopher K Fairley PhD, MBBS, Director, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgement

We thank the patient who has provided written consent to publish her clinical history.

Funding

Jason J Ong (number 1104781) is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship.