The common cold contributes to a high burden of disease in the general population despite its minor and temporary effect.1 The high prevalence and notable impact on quality of life with the common cold generates an economic burden greater than any other clinical condition.2 The common cold is typically managed through self-care, comprising use of antihistamines, antitussives, mucolytics/expectorants and decongestants. More than 40% of parents in Australia purchase over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medicines for their children.3–5 However, there is little evidence to support the efficacy of these medicines.6

OTC symptomatic medications for cough and cold raise particular concerns as a result of their potential undesirable effects (eg interactions, side effects and delay of diagnosis). For children under 6 years of age, the limited efficacy of certain cough and cold medicine constituents and the associated adverse reactions led the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) to advise against their use when they are not on prescription.7 OTC drug abuse was most often reported with codeine-based medicine and cough products (particularly dextromethorphan) in an older cohort.8

Consumers still seem to be poorly informed about appropriate use, efficacy and safety of OTC medicines for respiratory symptoms despite the risks.9,10 Although previous research focused on beliefs around OTCs for cough and cold medicines, gaps in the perceived knowledge and concerns of consumers are generally unknown.11,12

To provide more relevant patient information about OTC cough and cold medicines, this study aimed to explore consumers’ questions. We interrogated an extensive Australian database with enquiries from consumers about medication to determine gaps in their knowledge and concerns. Issues raised by Australian consumers can lead to more targeted and appropriate consumer medicines information for patients and their carers.

Methods

Data collection

We used data from the National Prescribing Service (NPS) Medicines Line collected by pharmacists at Mater Health Services in Brisbane between September 2002 and June 2010. This service was available to consumers nationwide with medication-related questions. Calls were documented using a standardised data collection form. The callers’ and patients’ demographics were recorded, together with the enquiry type, prior information received and motivation for the call. Up to three generic medicines related to the caller’s question could be documented and were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system.13 The question narrative was also recorded electronically for calls in the last 18 months of this service period.

Data management

We classified calls as ‘cough and cold’ when a query contained a medicine that was from the main ATC group for respiratory system and was available without prescription (Appendix 1, available online only). We excluded calls about complementary medicines and requests for consumer medicines information leaflets only. Questions involving paracetamol, ibuprofen and codeine were only selected when used in combination with OTC cough and cold medicines in order to filter out those most likely used for analgesia. We considered calls that were not about OTC cough and cold medicines as ‘rest of calls’.

Quantitative analysis

We conducted a retrospective quantitative analysis on all cough and cold medicine related calls. Comparisons between OTC cough and cold medicine calls and ‘rest of calls’ were performed using a t-test for continuous data and a chi-square test for categorical data. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant. We performed all statistical analyses using SPSS version 22.14

Narrative analysis

The most common enquiry for cough and cold medicine calls was ‘interactions’. Call narratives were available electronically for 18 months of service (1 January 2009 – 30 June 2010). All of the narratives of interaction-related calls were analysed by two pharmacists (TM and GM) to identify potentially clinically relevant interactions, using drug interaction literature and programs.15–18 Mechanism(s) of interaction, pharmacodynamics and/or pharmacokinetics were determined and common patterns identified. We assumed OTC cough and cold medication was added to the patients’ regular medicines and patients were not already experiencing symptoms from these in assessing interactions. Discordances were resolved through discussion.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Mater Health Services Brisbane, Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR submission 2012–68).

Results

Table 1. Characteristics of the patient and caller in ‘cough and cold’ and

‘rest of calls’ groups

|

|

|

Cough and cold

|

Rest of calls

|

P-value

|

|---|

|

Total

|

5503

|

117,702

|

|

|

Caller

|

|

|

|

|

Female, n (%)

|

4720 (85.8)

|

89,903 (76.5)

|

<0.001*

|

|

Age mean, years (± SD)

|

42.2 (± 15.8)

|

50.7 (± 17.5)

|

<0.001†

|

|

Age median, years

|

37

|

50

|

|

|

Relationship of caller,

|

|

|

<0.001*

|

|

Self, n (%)

|

3072 (55.8)

|

84,928 (72.4)

|

|

|

Child, n (%)

|

1789 (32.5)

|

14,925 (12.7)

|

|

|

Other, n (%)

|

642 (11.6)

|

17,849 (14.9)

|

|

|

Patient

|

|

|

|

|

Female, n (%)

|

3605 (69.4)

|

71,959 (67.9)

|

0.024*

|

|

Age mean, years (± SD)

|

31.3 (± 25.3)

|

47.1 (± 23.9)

|

<0.001†

|

|

Age median, years

|

30

|

49

|

|

|

Age categories

|

|

|

|

|

<1, n (%)

|

648 (12.5)

|

4944 (4.7)

|

<0.000*

|

|

1–14, n (%)

|

1058 (20.4)

|

6764 (6.4)

|

|

|

15–24, n (%)

|

311 (6.0)

|

6252 (5.9)

|

|

|

25–64, n (%)

|

2485 (47.8)

|

57,642 (54.4)

|

|

|

≥65, n (%)

|

694 (13.4)

|

30,320 (28.6)

|

|

|

*Chi2 test

†t-test

|

Quantitative analysis

A total of 5503 calls related to questions about OTC cough and cold medicines were extracted, with the remaining 117,702 calls regarded as ‘rest of calls’. Table 1 provides characteristics of the patients and callers.

The proportion of cough and cold calls increased annually from 2% (n = 150) in 2002–03 to 5% (n = 904) in 2009–10. Although many callers rang for themselves, 33% (n = 1789) called for a child. The percentage of calls related to children under 6 years of age in the cough and cold group was consistent throughout the years, fluctuating between 23–30%.

Table 2 provides a list of cough and cold therapeutic classes most commonly enquired about. The ‘top’ medicines were paracetamol (n = 882, 16%), pseudoephedrine (n = 837, 15%), phenylephrine (n = 800, 15%), loratadine (n = 621, 11%) and promethazine (n = 589, 11%). This was consistent throughout the years and per enquiry type.

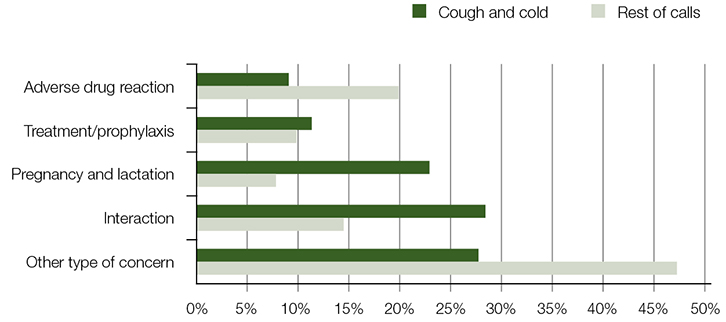

The types of questions asked by callers are provided in Figure 1. Compared with rest of calls, cough and cold calls more often related to potential interactions (29% vs 15%) and pregnancy/lactation (23% vs 8%). All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Concerns about cough and cold interactions with concomitant therapy differed considerably across patient age groups. The 1–14 years age group interaction questions often involved beta-lactam antibacterials/pencillins, while the 15–64 years age group involved antidepressants, and the ≥65 years age group involved cardiovascular medicines.

|

| Figure 1. Types of concerns |

Table 2. Cough and cold therapeutic medicine classes most commonly

enquired about

|

|

|

N (%)*

|

|---|

|

Antihistamines for systemic use

Sedating antihistamines

Less sedating antihistamines

Decongestants for systemic use

Other analgesics and antipyretics

Cough suppressants, excluding combinations with expectorants

Expectorants, excluding combinations with cough suppressants

|

3504 (63.7)

2359 (42.5%)§

1343 (24.2%)§

1600 (29.1)

882 (16.0)

721 (13.1)

386 (7.0)

|

|

*Represents the percentage of calls that had one of the ATC 3 cough and cold medicines listed

§Some calls concerned both sedating and less sedating antihistamines

|

Narrative analysis

Of 1570 cough and cold calls related to interactions, 248 electronically recorded narratives (15.8%) were analysed. Potentially clinically relevant interactions were identified in 20.2% of patients (n = 50), with more than one interaction for some patients (n = 62; Table 3).

Table 3. Potentially clinically significant pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions

|

|

|

Prescription medicine

|

OTC cough and cold medicine

|

Potential outcome§

|

|---|

|

Dynamic

|

SSRI

|

Decongestant

|

Irritability/insomnia; blood pressure effects¥

|

|

Sedating antihistamine

|

Sedation/drowsiness; blood pressure effects¥

|

|

SNRI

|

Decongestant*

|

Irritability/insomnia; blood pressure effects¥

|

|

TCA / TeCA

|

Pseudoephedrine

|

Irritability/insomnia; blood pressure effects;

Pseudoephedrine opposes effects of TCA on sleep

|

|

Phenylephrine

|

Blood pressure effects¥

|

|

Sedating antihistamine

|

Sedation/drowsiness; Blood pressure effects¥;

Dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation

|

|

Antihypertensive

|

Decongestant*

|

Blood pressure effects¥

|

|

Benzodiazepine and/or alcohol

|

Sedating antihistamine

|

Sedation/drowsiness

|

|

Antiepileptic

|

Sedating antihistamine

|

Sedation/drowsiness

|

|

Decongestant*

|

Lowers seizure threshold

|

|

Antipsychotic

|

Antihistamine

|

Sedative, blood pressure effects¥¤

|

|

Kinetic

|

SSRI/TCA; clarithromycin/erythromycin; metoclopramide; diphenhydramine

|

Antihistamine (sedating phenothiazine or loratadine)

|

Toxicity: significantly increased plasma levels of OTC antihistamine through CYP3A4 inhibition

|

|

Diltiazem

|

Codeine

|

Toxicity: significantly increased plasma levels of the opioid (codeine and active metabolite /morphine) through CYP3A4 inhibition

|

|

SSRI

|

Codeine

|

Decreased efficacy of codeine: blocks conversion of codeine to morphine through CYP2D6

|

|

SSRI, Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; TeCA, tetracyclic antidepressant

§Severity of outcome depends upon dose, co-medication and patient characteristics

*Decongestant includes oral (not intranasal) pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine

¥Blood pressure effects (hypo/hypertensive) depends on actual combination in cough and cold product

¤Effect aggravates when patient is hypertensive

|

Discussion

Our study found that people with questions about OTC cough and cold medicines are frequently concerned about their use in children. Parents are likely to treat children’s common cold symptoms with non-prescription medications without first consulting a health professional.5 The TGA’s warning against OTC cough and cold medication use in children may have reduced inappropriate use in Australia, but international literature found caregivers continue to give these medications to their children despite national recommendations.11,12 Significant child-related concerns should therefore still be anticipated. A relatively high number of questions were from female callers. It is possible these concerns are mainly expressed by mothers. Women are known to be more likely to seek health information in general, and their ‘carer role’ might contribute to more cough and cold related concerns.19

Overall, most concerns were related to antihistamines (64%) and interactions (29%). Consumers recognised the potential for interactions between regular medication and cough and cold medicines purchased OTC. While symptoms of the most common interactions are generally mild, some can have an impact on patient safety and should not be underestimated (eg sedation, lowering of seizure threshold). Insomnia and anticholinergic symptoms impair quality of life and might contribute to a longer recovery time, and could aggravate the already substantial economic consequences of the cold.2

The literature has found patients are unlikely to discuss their OTC medicine concerns with their general practitioner (GP).20,21 It might be best to provide appropriate consumer information when these medicines are purchased, advocating for their availability through consultation with a pharmacist.21 Recent Australian research on preferred medicines information sources highlighted that while 44% of consumers preferred spoken medicines information from a health professional, half of those surveyed preferred written options, including package inserts.22

This study has some important strengths. A large number of consumer questions about OTC cough and cold medicines were collected nationwide over eight consecutive years and the question narrative was recorded. This captured real consumers’ needs for medicines information.

Our study also has some limitations. The results are based on consumers who contacted a national medicine call centre. The callers might not represent all OTC cough and cold medicines users. Health-conscious medicine users are more likely to actively seek information about their medication concerns. In addition, help seekers might employ different strategies to obtain information (eg the internet or consulting their GP).22,23 However, it can be expected that similar questions are posed through these channels. Some of the medicines included in our selection could also be used for other medical conditions. Nevertheless, the inherent pharmacological characteristics of these agents would be expected to raise similar concerns, regardless of indication. As our study addressed medicine questions and not their real-time use, it was not possible to determine the extent to which interactions occurred. The clinical incidence of interactions between prescription and OTC medication is largely unknown and the reported incidence varies widely (4–50% of OTC users).24,25

In conclusion, there are considerable concerns and perceived knowledge gaps among the general population about frequently used OTC medicines for cough and cold, especially in children. As the trend towards the deregulation of medicine grows, such concerns and the associated interaction risks will only increase.26 Tailored consumer OTC cough and cold medication information is needed to address these identified information gaps.

Implications for general practice

- The public needs access to targeted information on OTC cough and cold medicines to address information gaps and concerns, especially about antihistamines and potential interactions.

- To reduce medication risks and concerns, prescribers should anticipate and actively inform patients taking chronic medications such as central nervous system depressants or antidepressants, about the potential risk of interactions with OTC cough and cold medicines.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge NPS MedicineWise (formerly National Prescribing Service, Australia), funder of Medicines Line and service provider since July 2010. We would also like to thank Mater Health Services for providing the raw service data from September 2002 to 30 June 2010 and Gabrielle Hartley, Mater Pharmacy Services, and Suzanne Bedford, University of Queensland, for database assistance.

Authors

Sanne Maartje Kloosterboer MD, Faculty of Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands, Faculty of Medicine

Treasure McGuire PhD, BPharm, BSc, GradDipClinHospPharm, GCHEd, Associate Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast; Senior Lecturer, School of Pharmacy, The University of Queensland, Brisbane; Assistant Director (Practice and Development), Mater Pharmacy Services, Mater Health Services, Brisbane, QLD

Laura Deckx PhD, Discipline of General Practice, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

Geraldine Moses DClinPharm, BPharm, FPS, FACP, Senior Pharmacist, Mater Health Services, Brisbane, QLD

Theo Verheij MD, PhD, MRCGP, Professor of General Practice, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Centre, Utrecht, Netherlands

Mieke van Driel MD MSc PhD FRACGP, Professor and Head, Discipline of General Practice, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD. m.vandriel@uq.edu.au

Competing interests: Sanne Maartje Kloosterboer received a Grant for Strategic Network Development, issued by the Internationalization Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, for accommodation and travel costs in Australia. Mieke van Driel received a grant from RACGP for the analysis of the consumer questions about complementary medicines.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Appendix 1. List of over-the-counter medicines for cough and common cold in Australia

|

|

ATC

|

Name

|

Access

|

|

R05CB01

|

Acetylcysteine

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

G04BA01

|

Ammonium chloride

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R02AA20

|

Amylmetacresol

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R01AC04

|

Antazoline

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AX09

|

Azatadine*

|

Pharmacist only medicine

|

|

R06AX19

|

Azelastine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R02AA16

|

Benzalkonium chloride

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R02AD01

|

Benzocaine

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R05CB02

|

Bromhexine

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AB01

|

Brompheniramine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AE07

|

Cetirizine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R02AA06

|

Cetylpyridium

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R02AA05

|

Chlorhexidine

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R06AB04

|

Chlorpheniramine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AE03

|

Cyclizine*

|

Pharmacist only medicine

|

|

R06AX02

|

Cyproheptadine*

|

Pharmacist only medicine

|

|

R06AX27

|

Desloratadine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AB02

|

Dexchlorpheniramine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R05DA09

|

Dextromethorphan

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R02AA03

|

Dichlorobenzyl Alcohol

|

Unscheduled

|

|

N02AA08

|

Dihydrocodeine

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AA02

|

Diphenhydramine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AA09

|

Doxylamine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AX26

|

Fexofenadine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R05CA03

|

Guaiphenesin

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R02AA12

|

Hexylresorcinol

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R06AX17

|

Ketotifen*

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R01AC02

|

Levocabastine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AE09

|

Levocetirizine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AX13

|

Loratadine#

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AD04

|

Methdilazine*

|

Pharmacist only medicine

|

|

R01AA05

|

Oxymetazoline

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R05DB05

|

Pentoxyverine

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R06AB05

|

Pheniramine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R02AA19

|

Phenol

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

RO1BA03

|

Phenylephrine

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R05DA08

|

Pholcodine

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AD02

|

Promethazine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R01BA02

|

Pseudoephedrine

|

Pharmacist only medicine

|

|

R05CA06

|

Senega

|

Unscheduled

|

|

R01AA09

|

Tramazoline

|

Pharmacy medicine

|

|

R06AD01

|

Trimeprazine* (alimemazine)

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R06AX07

|

Triprolidine*

|

Pack size and strength determine if Pharmacy medicine or Pharmacy only medicine

|

|

R01AA07

|

Xylometazoline

|

pharmacy medicine

|

|

* Sedating Antihistamines

# Less sedating Antihistamines

Unscheduled medicine = No restriction on access e.g. available from Supermarket

Schedule 2 = Pharmacy Medicine – Substances, the safe use of which may require advice from a pharmacist and which should be available from a pharmacy or, where a pharmacy service is not available, from a licensed person

Schedule 3 = Pharmacist Only Medicine – Substances, the safe use of which requires professional advice but which should be available to the public from a pharmacist without a prescription

|