Chronic vulvar pain (pain lasting more than 3–6 months, but often years) is common. It is estimated to affect 4–8% of women at any one time and 10–20% in their lifetime.1–3

Little attention has been paid to the teaching of this condition so medical practitioners may not recognise the symptoms, and diagnosis is often delayed.2 Community awareness is low, but increasing with media attention. Women can be confused by the symptoms and not know how to discuss vulvar pain. The onus is on medical practitioners to enquire about vulvar pain, particularly pain with sex, when taking a sexual or reproductive health history.

Vulvodynia

Table 1. Conditions that can result in chronic vulvar pain (provoked and unprovoked)

|

|

Condition

|

Comments

|

|---|

|

Vulvodynia

|

Can be localised or generalised, provoked or unprovoked: typical history and little to see on examination

|

|

Infection

|

More common

- Candidiasis: trial of suppression is worthwhile if chronic infection is suspected

Less common

- Bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis: can sometimes cause burning

- Genital herpes: usually episodic and distribution unilateral

|

|

Dermatoses

|

More common

- Eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis: abnormal examination, address skin care and consider a trial of topical corticosteroid

Less common

- Psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, plasma cell vulvitis: abnormal examination and need specific treatment

|

|

Vaginal atrophy and

atrophic vaginitis

|

Abnormal examination, trial of vaginal oestrogen

Lactational amenorrhoea can result in vulval dryness and dyspareunia due to hypoestrogenisation

|

|

Neoplastic

|

Vulval intra-epithelial neoplasia, Paget’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma: all uncommon but not to be missed, abnormal examination

|

|

Trauma

|

Recurrent traumatic tears: usually of the hymen ring and often accompanied by bleeding with sex, examine 1–2 days after sex if history is suggestive

Fissures of the posterior forchette

Vulvar trauma with childbirth

|

|

Vaginismus

|

Usually associated with LPV but occasionally occurs alone: refer for pelvic floor physiotherapy

|

|

Neurological

|

Pudendal nerve neuralgia: uncommon – refer to Nantes criteria24 for diagnosis

Referred pain from pelvic girdle, herpes neuralgia: usually unilateral

|

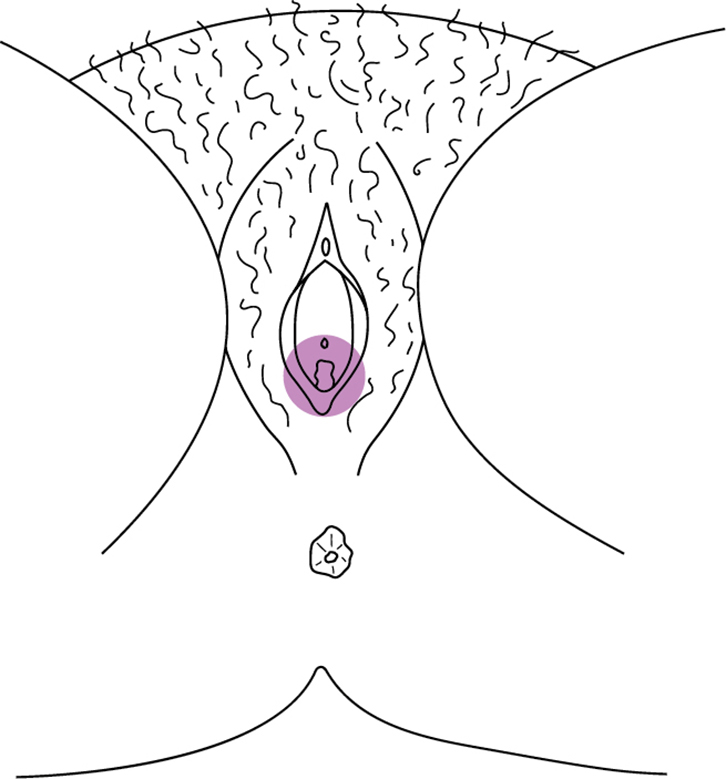

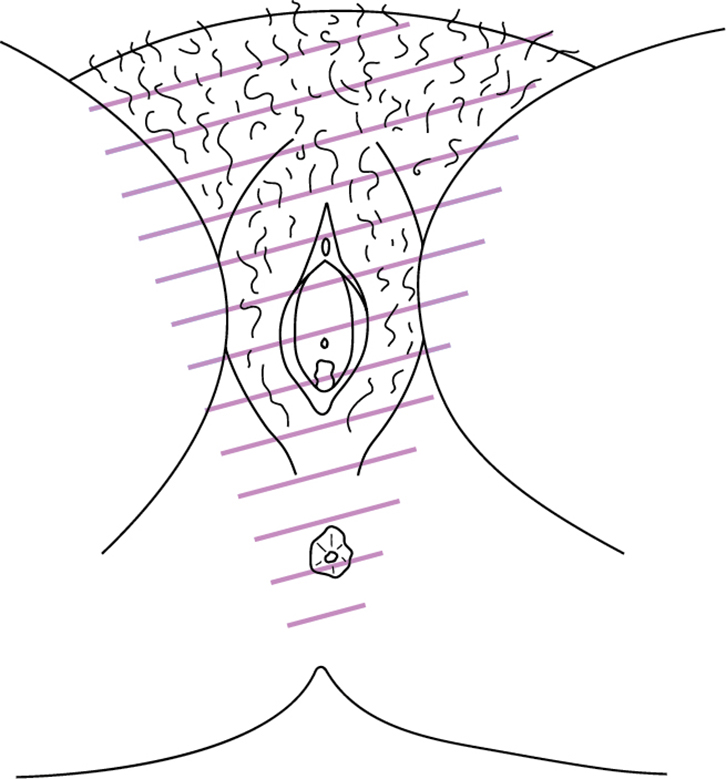

Vulvodynia is defined by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) as ‘chronic vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant findings or a specific, clinically identifiable, neurologic disorder’.4 It is diagnosed when other causes of vulvar pain have been excluded (Table 1) or when pain persists despite adequate management of these conditions. Vulvodynia is further classified as localised or generalised, and provoked, unprovoked or both. Most chronic vulvar pain falls into two broad groups: localised provoked vestibulodynia (formerly vestibulitis or vulvar vestibular syndrome) and generalised vulvodynia (formerly essential or dysaesthetic vulvodynia) (Figures 1, 2).

|

| Figure 1. Distribution of provoked pain in vestibule in LPV |

|

| Figure 2. Distribution of discomfort in generalized vulvodynia |

Localised provoked vestibulodynia (LPV) is by far the most common presentation and this article will focus on this subset. LPV is a well-recognised, chronic pain condition.

What is chronic pain?

Chronic pain is a disease entity in its own right, characterised by augmented central pain processing (central sensitisation) and lowered peripheral sensory threshold for pain (peripheral sensitisation).5 Chronic pain is estimated to affect approximately 18% of adult Australians.6 Symptoms are frequently localised to a particular part of the body (eg vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome or chronic low back pain) but can be generalised (eg fibromyalgia). Whatever the location or distribution of pain, it is now thought there is a common central pathology, which helps explain frequently observed comorbid symptoms of multifocal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance and mood changes.7 There is increased incidence of co-existent pain disorders and women with vulvodynia have a 2–3-fold increase in the likelihood of having another pain condition.8

It is not understood why some individuals develop chronic pain and others do not. It seems that some individuals experience heightened pain sensitivity and are more vulnerable to developing chronic pain. Pain sensitivity is in part genetically determined but also influenced by psychological and environmental factors.9 Chronic pain occurs with greater frequency in women with a past history of sexual or physical abuse. The association with vulvodynia is less clear, although some research indicates increased incidence.10

Localised provoked vestibulodynia

LPV is characterised by tenderness to gentle touch or pressure in the vulvar vestibule. There are localised neuroinflammatory changes within the mucosa, including increased concentration of pro-inflammatory peptides and hyperinnervation with C-fibres.11 These fibres are multimodal sensory fibres that, when stimulated, can result in prolonged burning. In addition, there is hypertonicity of the pelvic floor muscles, resulting in introital narrowing and muscle pain.

Vulvar discomfort is often described as burning or raw, but also stinging, tearing, stabbing or itchy. In the absence of touch or pressure, women are often symptom-free. Typically, pain is provoked by sexual intercourse, use of tampons and tight clothing. Pain or burning characteristically continues after intercourse, often lasting a few hours but sometimes several days (after sensation). Pain may be so severe as to preclude sexual intercourse.

LPV is divided into primary or secondary, depending on whether the pain arose before or after first sexual intercourse. This is an important separation because primary LPV can be more difficult to treat and secondary LPV may be associated with chronic candidiasis.

Women with primary LPV may report that they have never been able to use tampons because of pain and that their first attempted sex was so painful that they had to stop. Women with secondary LPV typically have previously had years of pain-free sex. In this latter group, there may be an identifiable pain-sensitising event, but often no trigger can be identified. Sometimes there is associated clitoral pain (clitorodynia) and clitoral touch or stimulation is unpleasant or painful.

Diagnosis

There are no specific tests. Diagnosis is made on the basis of a typical history, supported by examination findings and exclusion of other painful vulvar conditions (Table 1). Vulvodynia can co-exist with other vulvar conditions but become evident only when other conditions have been managed and pain persists. Chronic candidiasis, for example, is frequently implicated in the onset of LPV through the pain-sensitising effect of chronic inflammation and repeated painful sex. It is important, therefore, to look for candidiasis in women with LPV.

History

Box 1. Chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis*

|

|

Suggestive symptoms:

- Vulvar itch

- Swelling or splitting with sex

- Reduced lubrication (often there is little discharge with chronic candidiasis)

- Burning and rawness with sex

- Premenstrual flare of pain and/or itch

- Reduction in symptoms while using antifungal treatments

- Previous positive cultures or detection on a Pap smear

Note: cultures are often negative within 4 weeks of antifungal treatment.

Management:

Trial of candida suppression if suggestive symptoms, even if cultures negative

Treatment has to be prolonged as all antifungals currently available are fungistatic and yeasts proliferate when suppression is stopped

Oral treatments are preferable as they avoid potential contact dermatitis with prolonged topical treatments

A private prescription for fluconazole 28 x 50 mg capsules costs <$30. Prescribe 3 x 50 mg capsules in a single dose weekly. May need to continue suppression for 6 months or longer.

If no improvement in symptoms after 6 weeks of suppression and negative cultures, candidiasis is unlikely. Look for another diagnosis.

*Chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis is often referred to as recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in the literature. They describe the same condition. The term ‘recurrent’ arises because of the observation that symptoms improve or abate while using antifungal treatment and recur after stopping.

|

|

Box 2. Common co-existing pain conditions

|

|

Co-existing pain conditions include:

- Vulvodynia

- Painful bladder syndrome (interstitial cystitis or irritable bladder)

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Chronic pelvic pain (including endometriosis and dysmenorrhea)

- Fibromyalgia

- Migraine and chronic tension headache

- Chronic low back pain

- Chronic neck pain

|

|

The location and nature of pain are the keys to diagnosis. Questions to ask include:

- Is the pain localised to the vaginal entrance?

- Is the pain constant or with touch only, or both?

- Is there an after-sensation? If so, for how long?

- Is there a history to suggest chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis (Box 1)?

- Is there a history of eczema or dermatitis?

- Is there a comorbid pain disorder (Box 2)?

- Are there sleep problems, anxiety or depression?

Sensitively explore the effect of pain on sexual relationships and intimacy. What sort of touch is possible, including self-touch? Does pain prevent sexual intercourse? If in a relationship, how understanding is the partner?

Explore the patient’s understanding of the pain and her fears. Many women are worried that something serious, such as cancer or infection, is causing the pain. Many worry that it is ‘all in her head’ and this can set up a cycle of self-blame. The patient fears the pain and is anxious about her future. Fear and anxiety escalate pain.

Examination

|

| Figure 3. Demonstration of cotton tip tenderness in the vestibule |

It is important to carefully describe what you are going to do and seek permission for each step. If the examination is too painful or causing distress, stop.

Examination typically shows a very normal looking vulva. Redness of the inner vestibule is non-specific and seen in women without pain. Gently touch the vulva with a moistened cotton tip swab, moving from labia majora to the introitus to determine areas of altered sensation and pain. With LPV, there is marked tenderness to light pressure in the inner vestibule (Figure 3). Check pelvic floor muscles (unless pain precludes further examination). With one fingertip, palpate the pelvic floor. The puborectalis muscles are often contracted and tender.

If there is any suspicion of candidiasis, take a low vaginal swab for microscopy and culture. Speculum examination is not necessary and is often very painful. It is best avoided.

Management

The goal of treatment is to reduce pain and to improve quality of life and sexual function. There are published guidelines for the management of vulvodynia.12–14 All treatment guidelines recognise that management is multidisciplinary. There is no strong evidence of benefit for any treatment intervention.15,16 What works for one person may not work for another and it is a process of trial and error. Despite this, most women do improve with treatment.

A positive relationship between patient and clinician cannot be overestimated. For a woman to be believed, to have a name for her pain and to know that it is relatively common is the start to treatment. It is important to emphasise that pain does not signify damage. Reassure that this is a recognised condition with recommended treatments and that most women gain significant improvement over time. Some become pain-free (the nervous system is highly malleable and if pain can be wound up it can be wound down again). However, expectations must be realistic as the response to treatment is not immediate and treatment is often prolonged. It helps to explain the rationale for different treatment strategies and engage the woman in treatment choice. Understanding the potential benefits of a particular treatment has a positive effect on response.14,17

Give advice on genital skin care (Box 3) and treat co-existing vulvar conditions. Advise adequate lubrication with sexual activity, to reduce friction (sometimes pain has been largely due to dryness). Discuss temporary cessation of penetrative sex if there is significant pain or distress. Suggest reading material – this can be helpful for partners too (refer to Resources).

Box 3. Genital skin care

|

|

The basic principles are avoidance of potential irritants and improved skin moisture.

Common irritants:

- Soap and shower gels: wash with plain water or simple moisturiser or pH-adjusted wash for sensitive skin

- Genital hygiene wipes, including nappy wipes

- Pads and panty liners: stop using daily panty liners, as pad dermatitis is common; vulvodynia can make women more aware of normal physiological secretions (ie can make them feel wetter)

- Fabric softener

- Preservatives

- Perfumes (eg in toilet paper and talcolm powder)

- Urine and faeces (with incontinence)

- Medicinal and herbal products (eg tea tree oil, benzocaine, antifungals)

Improve moisture:

- Avoid prolonged contact with water as it is drying (eg swimming, long showers or baths).

- Moisturise after washing with a simple moisturiser (eg sorbolene or acqueous cream): use more frequently if needed; if skin is very dry use a heavier moisturiser.

- Protect skin with a water-resistant barrier before swimming or if using pads for menses or incontinence (eg vaseline or zinc and castor oil).

Use topical medications only if prescribed and as directed; stop if irritating and consult medical practitioner.

|

Physical therapy

Physiotherapy addresses pelvic muscle dysfunction. In our experience this may be the single most important intervention. It involves down-training, biofeedback and desensitisation (NOT Kegel exercises). Not all physiotherapists are trained in this area so check before referring. Few public hospitals offer this type of physical therapy.

Psychological and behavioural interventions

Encourage women to look at self-management strategies to reduce anxiety (relaxation, mindfulness or meditation).

Counselling is often helpful. The pain may have significantly affected relationships, intimacy and self-esteem. Some public hospitals have outpatient sexual counseling services. A mental healthcare plan may help offset costs if referred to a private psychologist.

Discuss sleep difficulties. Non-refreshing sleep tends to increase pain and reduce coping skills. Significant depression or anxiety needs specific treatment.

Topical treatments

Simple measures to manage mild, provoked pain include application of lignocaine 2% gel or 5% ointment to the vestibule 10–20 minutes before sex. Patients should be advised that these treatments sting for a few minutes after application, and to wipe off before penetration as these treatments will numb the partner.

Lignocaine 2–5% can be applied 2–5 times daily to the vestibule (more frequent application with lower strength). This may reduce peripheral sensory input, but should be stopped if it causes irritation. Other topical treatments are used less frequently and need to be formulated by a compounding pharmacist, which adds to the cost. These include amitriptyline 2–5% or gabapentin 2–6%, compounded in a neutral base and applied to the vestibule twice daily. Lower strengths are better tolerated, but should be stopped if irritation occurs. Application of a topical treatment has the added benefit of repeated touch and massage, which may help desensitise the vestibule, but the disadvantage of potential contact dermatitis.

Pain-modifying medications: neuromodulators

Standard analgesia is relatively ineffective in chronic pain.

Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are first-line treatment in chronic pain and help with sleep difficulties.12,18 The secondary amines nortriptyline and desipramine are preferred,18 but many practitioners will be more familiar with amitriptyline. Side effects are common and often dose-limiting. Start low (5–10 mg at night) and go slow (titrate up depending on side effects and benefit). Often, doses of 50–75 mg, or sometimes higher, are required. Beneficial effects may not be apparent for 4–6 weeks after achieving the therapeutic dose, and treatment needs to be continued for 6–12 months, if effective. Treatment should be discontinued if there is no effect after 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated dose.

The serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) duloxetine and venlaxafine have also been used for chronic pain and are indicated if there is significant comorbid depression or anxiety. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are less effective in chronic pain.18

Gabapentinoids are used if TCAs are contraindicated, not tolerated or not effective.13 This class has the advantage of few drug interactions. Pregabalin can be started at 75 mg and increased slowly, as tolerated. Lower starting doses can be used if there is significant sedation. Gabapentin, starting at 300 mg can be used if pregabalin is not tolerated.12 Other anticonvulsants are rarely used. Sometimes combining low-dose TCAs with gabapentinoids has an additive effect.19

Surgery

The place of surgery as a treatment is uncertain and controversial. In a small number of selected women with very localised vestibular pain, surgical excision of the painful area has been successful.13,20 However, this option is a last resort after other treatments have failed.

Other interventions

Intralesional injections of steroid and local anaesthetic, and botulinum toxin injections are discussed in the literature but these treatments are difficult to access and appear no more effective than other interventions.21,22 Low oxalate diets are no longer advocated as there is poor evidence to support use. Hypnotherapy and acupuncture are emerging as potential therapies, but evidence is limited.

Combined oral contraceptives and LPV

Some specialists believe that low-dose oral contraceptives result in hypo-oestrogenisation of the vestibule that predisposes to pain. A recent epidemiological study found no association of oral contraceptive use and vulvodynia.3

Generalised unprovoked vulvodynia

Generalised unprovoked vulvodynia is less common and typically presents in older women. Onset may be sudden or gradual and the distribution is more diffuse than in LPV. Any pressure on the vulva, such as prolonged sitting or bike riding, can aggravate the pain, but intercourse may be pain-free. Low-dose TCAs or gabapentinoids are often effective in reducing pain.13,23

If referrals are needed, the Australian and New Zealand Vulval Society has a list of doctors who specialise in vulval medicine and can be accessed through their website (refer to Resources).

Case 1

A woman aged 18 years has never been able to use tampons because she experiences pain when inserting them. There is no pain at other times. When she first attempted sexual intercourse with a male partner she had to stop because the pain was so bad (rated 10/10 on a pain scale). On examination, her vulva looked completely normal apart from marked contraction of the pelvic floor, making the vaginal entrance look ‘sucked in’, and erythema in the medial vestibule. Gentle touch with a cotton tip swab at the vaginal entrance resulted in a visible pelvic floor contraction and was markedly tender (rated 10/10). She could not tolerate a single-digit vaginal examination. A culture for yeasts was negative. She was referred for physiotherapy and prescribed low-dose TCAs. Her condition improved gradually over the next year and she was able to initiate a sexual relationship. She also benefited from seeing a clinical psychologist as there were underlying issues relating to permission to have premarital sex. She stopped taking the TCAs after 1 year and had no increase in pain. She is now able to have comfortable sex as long as she is relaxed and has adequate lubrication. The pain never fully resolved but she is able to cope well and have a fulfilling relationship.

Case 2

A woman aged 25 years, in a relationship for 3 years, started to experience painful sex 18 months ago and stopped having sex because the pain was so unpleasant (rated 7–8/10 on a pain scale). Symptoms first occurred after several episodes of thrush following repeated courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. She used over-the-counter antifungal agents to treat the thrush infection. Around this time she had a very painful speculum examination. The pain persisted despite negative cultures for yeasts. She was tender with gentle cotton tip pressure in the vestibule and her pelvic floor muscles were tense and tender. Repeat cultures for yeast were negative but given the history of thrush, she consented to a trial of thrush suppression with weekly 150 mg fluconazole. This did not improve her symptoms and she stopped fluconazole after 6 weeks. She was referred for physiotherapy and used topical lignocaine 2% gel 2–3 times daily. She gradually improved over the next 6 months, but then had a flare-up of pain. There had been significant discord in her relationship with her partner and the pain flared up with her distress and anxiety. She was referred for sexual counselling. Over the next year the relationship and her pain improved and she decided she no longer needed treatment.

Case 3

A woman aged 60 years reported a 3-year history of increasing constant vulvar burning. She was able to have sex with only mild exacerbation of discomfort. Vaginal oestrogens increased moisture but did not help with the pain. Examination was unremarkable except for tenderness with touch over the lateral vestibule and labia. She had no pelvic floor tenderness. She started low-dose nortriptyline (after having an electrocardiogram, which was normal) and at 30 mg nocte began to notice reduced burning. She remained on this dose and eventually the pain resolved. After 6 months she was able to reduce and stop the medication with no relapse.

Authors

Helen Henzell MBBS, FAChSHM, Sexual Health Physician, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Carlton, VIC, and Action Centre, Family Planning Victoria, Melbourne, VIC. hhenzell@mshc.org.au

Karen Berzins, MBBS, FAChSHM, Sexual Health Physician, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Carlton, VIC, and Mercy Hospital for Women, Heidelberg, VIC.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Resources

- Melbourne Sexual Health Centre. Fact sheets on genital skin care and vulvodynia, www.mshc.org.au

- Melbourne Sexual Health Centre. Pictures of genital skin conditions including lichen sclerosus and VIN, www.stiatlas.org

- The Pelvic Pain Foundation recently launched an Australian website with excellent patient information about a number of types of pelvic pain affecting both women and men. There are extensive clear and up-to-date patient information sections with printable leaflets. There are also resources for finding practitioners throughout Australia. It is highly recommended, www.pelvicpain.org.au

- The National Vulvodynia Association has up-to-date and comprehensive information for women and their partners, and online CME-accredited course for medical professionals, www.nva.org

- The Australia and New Zealand Vulval Society provides a list of doctors who specialise in vulvar medicine, www.anzvs.org

- Butler D, Moseley L. Explain pain. 2nd edn. Adelaide: NOI Group Publications, 2013. This is a very helpful book for patients and health providers. This book does not specifically address vulvodynia but discusses chronic pain in readily accessible language. It is available in electronic and hard copy format.