The idea of using the immune system to treat cancer is traceable to the 1890s, the time of Pasteur. The first clinician to use an immunological approach was the surgeon William Coley of Memorial Hospital, New York (now Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute). Coley noted that, rarely, cancers would regress spontaneously, but only when local abscesses or other purulent bacterial infections were present. ‘Coley’s toxins’ (cocktails of live bacteria) were repeatedly injected to produce prolonged pyrexia, but the associated high mortality first led to vaccines with killed bacteria and, ultimately, abandonment of the approach in the 1930s.1

Australian Nobel Laureate Macfarlane Burnet was a devotee of the theoretical links between cancer causation and immunity, and advanced his radical hypothesis of ‘tumour immune surveillance’ in the 1950s. Burnet proposed that, as well as protecting against pathogens, the immune system routinely detects and destroys pre-malignant cells and that clinical cancer, therefore, reveals ‘failed immune surveillance’. However, it took 50 years for this view to gain acceptance.2 In support of Burnet, very rare spontaneous regressions of advanced melanoma were typically accompanied by vitiligo (loss of normal skin pigmentation), suggesting the immune system was responding to antigens shared by normal and malignant melanocytes. By the 1990s, advanced technologies proved that clones of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) could kill both normal and malignant cells presenting fragments of abundant melanocyte differentiation antigens such as tyrosinase or Melan A/Mart-1.3

Further evidence of cancer immune surveillance came from international registries of chronically immunosuppressed, solid organ transplant patients; by far the greatest relative risks were for cancers caused directly by viruses.4 Formal demonstration of ‘immune surveillance’ in the absence of oncogenic viruses came in the 1990s when Schreiber showed that mice lacking the immune effector molecule interferon-gamma (IFNγ) have a high incidence of spontaneous sarcoma and lung adenocarcinoma.5 Our laboratory reported that mice congenitally lacking perforin, a protein toxin essential for CTL and natural killer (NK) cells to kill target cells, develop fatal B cell lymphoma.6 In humans with colorectal cancer, Galon et al made the remarkable finding that infiltration of cancerous tissue with activated CD8+ T cells is a better predictor of long-term survival than the extent of anatomical spread of the tumour.7 More recently, we also showed that patients who inherit mutations of the perforin (PRF1) gene develop a variety of blood cancers during childhood/adolescence.8–10

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Being derived from self, malignant cells express few ‘foreign’ antigens (those arising from mutation), so most approaches over the decades aimed to make cancer cells visible to the immune system (immunogenic). Numerous vaccines combined patient antigen presenting cells (APC, commonly dendritic cells), purified cancer antigens and an adjuvant such as a cytokine to activate CTL responses, but a reproducible benefit was not achieved in any disease. In retrospect, the dramatic success of immune checkpoint blockade, even in advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and renal cancer indicates that many cancers are actually spontaneously immunogenic, but the immune response is inhibited by factors in the tumour microenvironment.11

What is an immune checkpoint?

Checkpoints enable us to limit normal immune responses, both to pathogens and self-antigens. Two signals are required to activate a cellular immune response. Each individual CD8+ CTL expresses a clonotypic receptor that binds a peptide fragment presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on the target cell surface (signal 1). A second, co-stimulatory signal is also required for a robust, sustained response leading to target cell death, cytokine secretion and the formation of memory T cells. Signal 2 is generated by binding of CD28 with ligands B7-1 (CD80) or B7-2 (CD86) on the target. Some days later, a ‘checkpoint’ is applied: stimulatory CD28 is replaced on the T cell surface by inhibitory CTLA-4, and the signal is

switched off.

Many cancers aberrantly express ligands for CTLA-4 at high levels, thus imposing a strong negative signal. Therapeutic ‘checkpoint inhibitor’ antibodies such as anti-CTLA-4 (epilumumab, ‘Yervoy’) block this interaction, to disinhibit and amplify a pre-existing immune response to cancer. The second critical inhibitory receptor/ligand combination targeted by checkpoint blockade is between T cell PD-1, and PD-L1 or PD-L2 on cancer cells and APCs. This interaction occurs later in the immune response and leads to inactivation through ‘exhaustion’ or programmed death (thus ‘PD’) of the CTL.

Immune checkpoints targeting the PD-1 pathway have generated high interest, with overall response rates across tumour types averaging 20–30%. This includes responses in melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, small-cell lung cancer, kidney cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, hepatocellular cancer, bladder cancer and breast cancer. Early clinical data in patients with melanoma indicate that combined blockade of both CTLA-4 and PD-1 (ipilimumab/nivolumab) pathways leads to even better survival.

Checkpoint antibodies are administered by intravenous infusion and have half-lives of about three weeks. Repeated administration is necessary and we urgently need to decipher when treatment can safely be tapered, so that costs can be contained. Although well tolerated overall, about 10% of checkpoint blockade recipients develop serious autoimmune effects, such as inflammatory colitis, myocarditis, pneumonitis or skin rashes, that require specific management.12,13

Repurposing anticancer antibodies with chimaeric antigen receptor T cells

Therapeutic antibodies, either ‘naked’ or conjugated to cancer drugs or radioactive isotopes (both for imaging and therapy), have been used for many years, and can mediate their effects via the immune system. For example, trastuzumab (Herceptin), which binds the HER2 antigen on breast cancer, has two effects: apart from blocking growth signals to cancer cells, its Fc (non–antigen binding) domains also engage circulating NK cells, enabling them to directly kill cancer cells through antibody‑dependent cellular cytotoxicity.14

In chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, the payload delivered by antibodies consists of potent anticancer T cells rather than toxins or isotopes. This form of adoptive T cell immunotherapy sidesteps the need for pre-existing cancer immunity. Rather, an immune response is generated by manipulating a patient’s own CD8+ T cells ex vivo, with subsequent re-infusion of the activated cells into the patient.

The technology that preceded CAR T cells was tumour infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy. TILs present in a fresh surgical specimen are isolated in the lab, induced to proliferate and become ‘activated’ with tumour antigen and growth factors such as interleukin (IL)-2, and then re-infused with IL-2 to sustain them in vivo. Encouraging responses were noted in patients with melanoma and renal cancer, particularly where patients had received ‘pre-conditioning’ chemotherapy, but complete response rates have rarely exceeded 7% in large clinical trials, and benefit is limited by toxicity of co-administered systemic IL-2.15

CAR T cell therapy has recently been shown to overcome these limitations. It uses replication-deficient retroviruses or lentiviruses to express, on a patient’s CD8+ T cells, antibody-like receptors capable of binding to a target antigen on cancer cells. Key for success are twin signalling motifs engineered into cytoplasmic domains of the CAR, which mimics the two signals (T cell receptor and co-stimulatory CD28), enabling the T cells to produce their own IL-2 in vivo. When a CAR T cell encounters a cancer cell, the result is antigen-driven proliferation, cytokine secretion, longevity and powerful perforin-mediated killing of cancer cells.16

Generally, 1–10 billion CAR T cells are expanded in specialised ‘clean rooms’ over 10–12 days. Single infusions of CAR T cells have been highly effective in lymphoid malignancies, particularly acute lymphocytic leukaemia, where the targeted antigen is the B cell differentiation antigen CD19 (Figure 1), but other B cell malignancies and solid cancers are currently being studied in extensive clinical trials (Table 1). In contrast to TILs, CAR T cells are achieving complete and durable remission in 50–80% of paediatric acute lymphocytic leukaemia, even after all other treatment options have failed.

Figure 1. In May 2010, when Emily Whitehead was 5 years of age, she was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL). Her cancer resisted several rounds of chemotherapy (left). In April 2012, she was enrolled in a Phase I trial of CD19-CAR T cell therapy and within a month, her disease went into remission and she is still cancer free today (right) (PMID: 25317870).

Photos reproduced from Emily ‘Emma’ Whitehead: My journey fighting leukemia, with permission from Emily Whitehead Foundation

Table 1. Published reports of CAR T cells in clinical trials

|

Cancer type

|

Target antigen

|

Year reported

|

Number of patients

|

Responses

|

Reference

|

|---|

|

ALL

|

CD19

|

2014

|

30

|

27 CR

|

20

|

|

AML

|

Lewis Y

|

2013

|

4

|

0

|

21

|

|

Colorectal and breast

|

CEA

|

2002

|

7

|

Minor response in 2 patients

|

22

|

|

Colorectal

|

TAG-72

|

1998

|

16

|

1 SD

|

23

|

|

Neuroblastoma

|

CD171 GD2

|

2007 2011

|

6 19

|

1 PR 3 CR

|

24 25

|

|

Ovarian

|

ɑFR

|

2006

|

12

|

0

|

26

|

|

RCC

|

CAIX

|

2011

|

11

|

0

|

27, 28

|

|

Prostate

|

PSMA

|

2013

|

5

|

2 PR

|

29

|

|

Sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumour, desmopastic small round cell tumour

|

HER2

|

2015

|

17

|

4 SD

|

30

|

|

ɑFR, alpha folate receptor; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CR, complete response; OR, objective response; PR, partial response; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SD, stable disease

|

|

The immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment

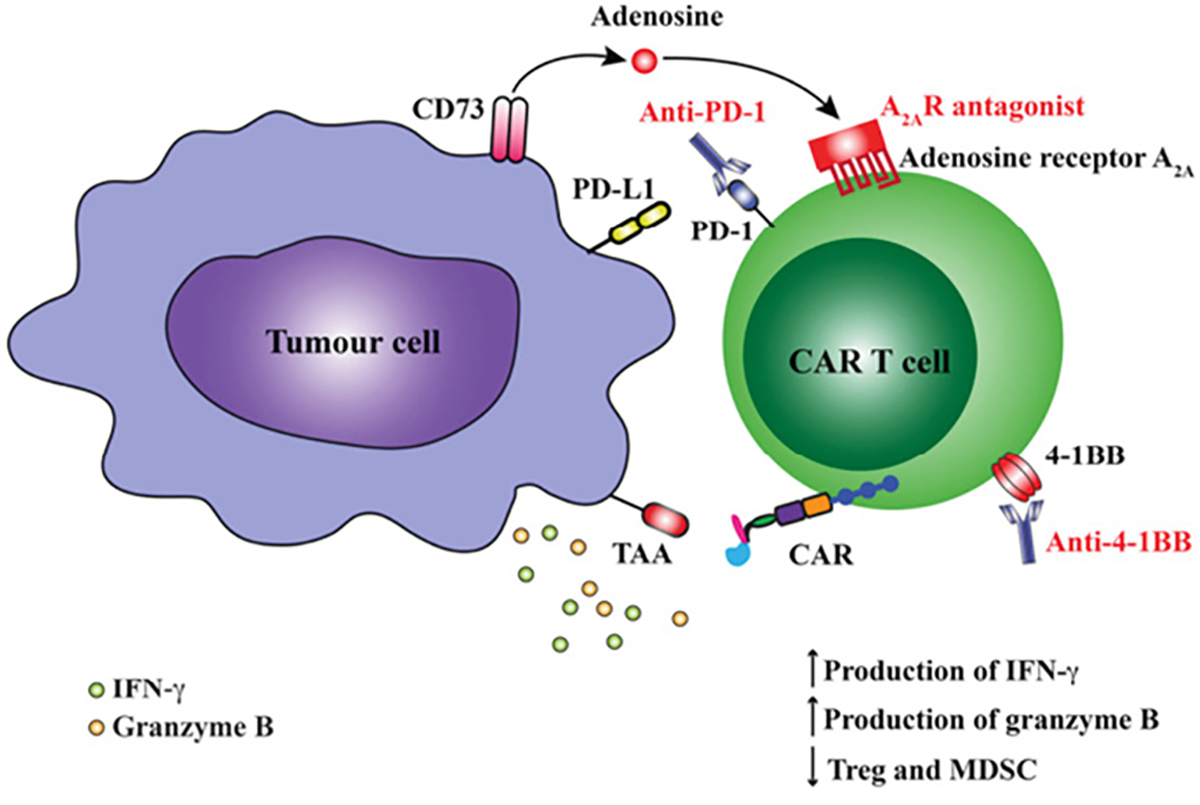

Why are checkpoint blockade and CAR T cells not universally effective? There are many reasons, but local suppression of the immune system by cancer is clearly a major contributor. The genetic instability of cancers means they can stop expressing antigens targeted by T cells, or lack the mechanisms that present them. Cancer cells may ‘switch on’ immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGFß or IL-10, or induce local stromal cells to do so. The tumour may now attract suppressive ‘regulatory’ T cells (Treg) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which normally prevent autoimmunity. Depleting these negative influences with other therapeutic antibodies is now being combined with checkpoint blockade or CAR T cells (Figure 2). In other instances, suppressive metabolic by-products of cancer cell metabolism (eg adenosine) can be neutralised with new drugs that block production or prevent their binding to receptors.17

Figure 2. Blockade of immunosuppression or activation of co-stimulatory pathways augment anti-tumour responses by CAR T cells. CAR activation following engagement of tumour-associated antigen (TAA) leads to upregulation of both inhibitory receptors on CAR T cells including programmed death-1 (PD-1) and adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) or activation receptors such as CD137 (4-1BB). Interaction of PD-1 with its ligand PD-L1 expressed on the tumour cell surface or binding of adenosine to A2AR can reduce functional responses by T cells. Blockade of PD-1 using an anti-PD1 mAb or A2A using a specific A2AR antagonist can augment CAR T cell function. Similarly, the use of an mmune agonist antibody such as anti-4-1BB can increase CAR T cell function and reduce frequency of regulatory cell types such as Treg and MDSCs within the tumour microenvironment.

Other immune-based cancer preventives and therapies

While these major advances have greatly spurred interest in cancer immunotherapy, some less-heralded approaches have contributed sporadically over many years. ‘Non-specific’ immune stimulation by repeated BCG immunisation can be effective in advanced bladder cancer. Vaccines against oncogenic viruses are potent cancer preventives, but ineffective therapeutically. Vaccines for hepatitis B (a major cause of hepatocellular cancer) and oncogenic human papillomavirus strains (cervical, anal, and some head and neck cancers) are notable, and further opportunities exist if Epstein–Barr virus (B cell malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma), Helicobacter pylori (gastric cancer) and human immunodeficiency virus (Kaposi sarcoma) infections can be prevented. Finally, allogenic bone marrow transplantation, which restores haematopoiesis after high-dose chemoradiotherapy, also provides donor T and NK cells that recognise residual cancer cells as foreign, and induce a beneficial ‘graft versus leukaemia’ effect.

Future challenges and opportunities

After 120 years, countless setbacks and decades of scepticism, immune-based therapies for cancer are here to stay (Table 2). Despite major recent advances, we have barely commenced learning how to best apply these emerging treatments, rationally combine them, or combine them with established treatments. Some conventional anticancer drugs such as lenalidomide (for multiple myeloma) have immune-stimulatory activity that can synergise with other immune-based approaches.18 Also exciting is the realisation that radiation therapy may amplify the immune response to cancer; we are still in the early stages of optimising the dose of radiation and understanding which patients are likely to benefit.19

Dozens of clinical trials for checkpoint inhibitors alone are open across Australia (www.australiancancertrials.gov.au) and demand is sure to grow. We urgently need biomarkers to predict which patient will respond, as a course of antibody-based treatment may cost the community or individual tens of thousands of dollars. Investment in molecular pathology and clinical trials infrastructure should be a priority for both government and pharmaceutical companies, as bottlenecks are already appearing. Ethically, new therapies must first be trialled in patients in whom the current standard-of-care treatment has failed, but eventually, immunotherapy may have an impact at earlier stages of disease, where cancer-related immunosuppression will present fewer obstacles.

For CAR T cells, there is great need to identify new target antigens for solid tumours. B cell cancers, where CD19/CD20 are effective targets, comprise about 5% of all cancer in Australia and the huge unmet clinical need in lung, oesophageal, brain and pancreatic cancers must be addressed. Currently, the cost of an autologous CAR T cell vaccine is comparable to bone marrow transplantation, but this would drop drastically if an ‘off-the-shelf’ solution, such as allogenic CAR T cells, becomes feasible, or with technological advances that simplify sterile production.

After decades of promise, there is much excitement for cancer immunologists and oncologists, and even greater hope and optimism in the cancer community.

Table 2. Current immunotherapies for cancer

|

Immunotherapy

|

Target antigen

|

Clinical indication

|

Reported toxicities

|

|---|

|

*Ipilimumab (Yervoy)

|

CTLA-4

|

Various; Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, AML, CML, CLL, NHL, melanoma

|

Arthritis, hyperthyroidism, pneumonitis, colitis, bowel perforation, vitiligo, hypophysitis

|

|

*Nivolumab, pembrolizumab

|

PD-1

|

Melanoma, RCC, NSCLC, prostate

|

Colitis

|

|

*Alemtuzumab

|

CD52

|

CLL

|

Destruction of normal leukocytes, leading to susceptibility to infections

|

|

*Rituxumab

|

CD20

|

Lymphoma

|

Suppression of B cells leading to deficiency in immunoglobulin and infections

|

|

*Trastuzumab (Herceptin)

|

HER-2

|

Breast

|

Cardiac toxicity

|

|

*IFN-ɑ

|

|

CML cutaneous T cell lymphoma

|

Thyroiditis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosis associated with auto-antibodies

|

|

*IL-2

|

|

Renal cell carcinoma, melanoma

|

Acute cardiorespiratory failure, hypothyroidism, myasthenia gravis, type 1 diabetes mellitus and myositis

|

|

*Sipuleucel-T cancer vaccine (Provenge)

|

Prostate-specific antigen

|

Prostate

|

Fever, chills, fatigue, back and joint pain, nausea, and headache, high blood pressure

|

|

TCR gene-modified T cells

|

MART-1, gp100

|

Melanoma

|

Vitiligo

|

|

†CAR-modified T cells

|

Various antigens ie CD19

|

Lymphoma, ALL, CLL

|

B cell depletion

|

|

*FDA-approved for specific clinical indications

†Refer to Table 1

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; RCC, renal cell cancer

|

Authors

Joseph A Trapani MBBS, FRACP, PhD, FFSc (RCPA), FAHMS, Executive Director, Cancer Research, and Head, Cancer Immunology Program, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Vic. joe.trapani@petermac.org

Phillip K Darcy PhD, Group Leader and Head, Cancer Immunotherapy Laboratory, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Vic

Competing interests: None

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Program grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). PK Darcy was supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (#1041828).