Drinking behaviours that increase the risk of alcohol-related harm (ie risky drinking) occur in one-quarter of Australian adult general practice attendees.1 General practitioners (GPs) are therefore ideally placed to detect risky drinking early and provide brief interventions.2

However, despite the development of validated alcohol-screening questionnaires,3 evidence of brief interventions’ efficacy,4 and guidelines urging the uptake of both of these,5–7 few GPs have embedded early detection practices into routine care.8 There are practical barriers to doing so (eg lack of time and resources),9 and barriers relating to consultation dynamics and sociocultural attitudes to drinking.10

Patients’ perspectives on alcohol discussions with GPs are complex. Patients seem to expect, but have reservations towards, GPs questioning their drinking behaviours;11–13 however, the explanation for this phenomenon is unclear. Earlier, we found in a survey experiment of general practice patients that the acceptability of alcohol enquiry seemed to vary markedly depending on the reason for presentation. We found that enquiries within the ‘SNAP’ (smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity) framework14 seemed to improve acceptability.15

In this study, we sought to understand the results of the survey experiment more deeply,15 and to explain patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards the acceptability of receiving alcohol enquiry from GPs. Pragmatic early detection and brief intervention implementation strategies in general practice need to be informed by patients’ perspectives.16

Methods

Study design

We used grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss) as our research method.17 This qualitative method involved:17,18

- coding the data into themes, categories and concepts

- an iterative approach to sampling, where earlier analyses guided further data collection

- using constant comparison in analyses to illuminate the emergence of concepts

- constructing an explanatory framework ‘theory’, that was ‘grounded’ in the data.

We chose this research method as it is suited to developing understanding of the actions, interactions and emotions of people within their social context, and it aligned with the focus of our research – the complex interactions between patient and doctor. This method was consistent with our constructivist ontological perspective, which placed the researchers (Australian medical practitioners and student) as participants in the research – ‘concept and theories are constructed by researchers out of stories that are constructed by research participants who are trying to explain and make sense out of their experiences’.17

This study was approved by the University of New South Wales Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (#HC14074).

Context

We have described the project setting previously in another article.15 In brief, this study was conducted in an established teaching general practice clinic, with five full-time equivalent GPs, located in an inner-city suburb of Sydney, Australia, in mid-2014. This was a suburb where the average age was 35 years, unemployment was at 6.6%, and 25% of households spoke two or more languages. Three of the authors, CT, CH and NZ, are GPs; CT and CH were clinicians at the practice. LL was a medical student researcher.

Participants

We interviewed a total of 23 participants (Table 1). They were recruited from respondents of a postal questionnaire that was sent to all adult patients who attended the clinic during a single week in May 2014.15 Around half (68 of 144) of the survey respondents indicated they were willing to be contacted for interviews to explore their perception of alcohol discussions with GPs. We had access to individual participants’ demographics from the survey.15

We sampled purposively – recruiting participants selectively so that there was a wide variation in age, sex, healthcare utilisation and drinking risk. We had planned to interview up to 25 participants. Theoretical saturation was likely to have been reached at 17 participants and we stopped further sampling after we reached 23 participants.

Table 1. List of participants

|

|

#

|

Age

|

Sex

|

Married or regular partner?

|

Country of birth*

|

Highest level of education

|

Employment status

|

New patient?

|

No. of visits in past year

|

No. of regular medicines

|

Drinking status†

|

|---|

|

1

|

67

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

High school

|

Retired

|

No

|

6

|

5

|

Low risk

|

|

2

|

60

|

M

|

N

|

Australia

|

High school

|

Pension

|

No

|

14

|

16

|

Non-drinker

|

|

3

|

65

|

F

|

Y

|

Canada

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

5

|

2

|

Risky

|

|

4

|

45

|

F

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

3

|

2

|

Low risk

|

|

5

|

83

|

M

|

N

|

Czech Republic

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

7

|

3

|

Low risk

|

|

6

|

64

|

F

|

N

|

Australia

|

High school

|

Pension

|

Yes

|

12

|

3

|

Non-drinker

|

|

7

|

59

|

F

|

N

|

United Kingdom

|

High school

|

Unemployed

|

No

|

10

|

1

|

Risky

|

|

8

|

74

|

F

|

N

|

New Zealand

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

3

|

1

|

Risky

|

|

9

|

32

|

F

|

N

|

Australia

|

University

|

Unemployed

|

No

|

10

|

1

|

Risky

|

|

10

|

30

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Domestic duties

|

No

|

15

|

1

|

Low risk

|

|

11

|

81

|

M

|

Y

|

United Kingdom

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

5

|

1

|

Risky

|

|

12

|

34

|

F

|

N

|

Tonga

|

University

|

Employed

|

Yes

|

2

|

0

|

Low risk

|

|

13

|

56

|

F

|

Y

|

Australia

|

High school

|

Pension

|

No

|

16

|

4

|

Non-drinker

|

|

14

|

28

|

F

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

6

|

0

|

Non-drinker

|

|

15

|

63

|

F

|

N

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

6

|

6

|

Risky

|

|

16

|

55

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

5

|

0

|

Risky

|

|

17

|

54

|

F

|

N

|

Sri Lanka

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

2

|

0

|

Low risk

|

|

18

|

91

|

M

|

Y

|

New Zealand

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

13

|

9

|

Non-drinker

|

|

19

|

34

|

F

|

Y

|

United Kingdom

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

6

|

2

|

Low risk

|

|

20

|

44

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

5

|

2

|

Risky

|

|

21

|

72

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

University

|

Retired

|

No

|

6

|

4

|

Risky

|

|

22

|

25

|

F

|

N

|

Australia

|

University

|

Employed

|

No

|

10

|

4

|

Low risk

|

|

23

|

50

|

M

|

Y

|

Australia

|

High school

|

Pension

|

No

|

90

|

11

|

Risky

|

|

*No participant identified as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person

†Risky drinker: AUDIT-C ≥5 in men and ≥4 in women1

|

Semi-structured interviews

To avoid participant coercion, CT and CH were not involved in the recruitment of patients for interviews, which were conducted by LL. Written consent was obtained from all participants. Each interview was approximately 30 minutes in length, conducted between June and August 2014, and recorded using a digital audio device. The interviews were held at the participant’s home, a local café, or a private room in the clinic, depending on the participant’s preference. They received a $5 gift voucher as reimbursement.

The interviews commenced with the opening question: ‘What are your thoughts on GPs asking you about your drinking?’ Participants were encouraged to share their views regarding the acceptability of alcohol enquiry, their past experiences with GPs, and their personal health beliefs. Prompts including ‘Do you think it is part of a GP’s job?’, ‘What situations would make it acceptable/unacceptable for you to receive alcohol enquiry?’, and ‘Could you describe an experience where you have been asked about your drinking?’ were used if certain issues did not arise naturally. When results of the survey experiment became available,15 some of the findings were explored in the interviews.

Data analysis

Initial transcripts of the interviews were manually edited by LL to remove identifying details in order to preserve participants’ anonymity from the GP researchers who might be their treating physician. These modified transcripts were imported into QSR International NVivo 10 software.

Analysis of the data began line by line with open coding. Similar codes were organised into provisional themes and concepts. Those salient to our research aims were highlighted and organised into categories, and we used the constant comparison technique in examining data from new transcripts.17 Extensive memos were kept to track and refine ideas. Query matrices and tree maps were used to visualise interactions in the data.

CT and LL met fortnightly during data collection and analysis to discuss interpretations of the data. Relationships between categories were examined on a whiteboard using diagrams. Earlier models were tested for validity against data from later transcripts, and these models guided further data collection (theoretical sampling). Our final model was refined through an iterative process and debated in depth by the entire research team until consensus was reached.

Results

|

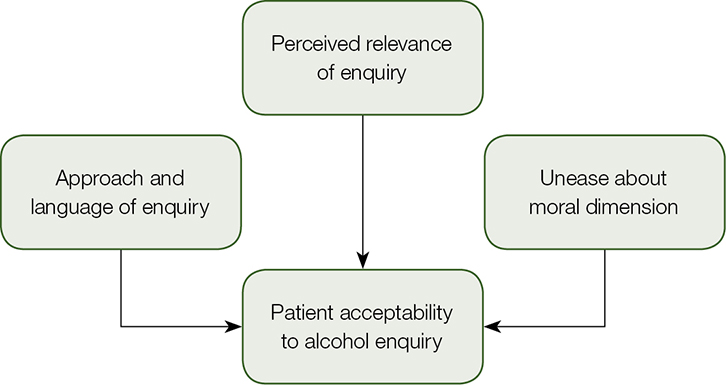

| Figure 1. Factors that influence patients’ acceptability to alcohol enquiry |

We developed a model that might explain the influences on patients’ acceptability of alcohol enquiry (Figure 1). The model consisted of three within-consultation factors:

- perceived relevance of the alcohol enquiry dialogue to the consultation

- approach and language used in the patient–doctor interaction

- unease regarding the moral and stigmatising dimension of alcohol consumption.

Perceived relevance of alcohol enquiry

In their opening statement, almost all participants considered alcohol enquiry by GPs to be appropriate and legitimate; it was seen as part of collecting a thorough medical history. Alcohol consumption was largely regarded by participants to be a health issue that could potentially affect the diagnosis and management of illness.

I would see it as very important, [be]cause it’s about general health and wellbeing, and alcohol use impacts various medical conditions. – P19

When asked to elaborate, participants volunteered examples such as annual health checks, updating medical records and health promotion activities. Some participants expected to receive lifestyle advice from their GPs.

I think it’s necessary if it is likely to relate to advice in regard to their health, which is probably why most people are here. In order to give complete and best advice, it’s necessary to understand factors like your environment, and that would include alcohol. – P8

However, the same participants went on to qualify that doctors should consider other contextual factors before initiating alcohol enquiry. It seemed that enquiry might not be appropriate during a consultation if the purpose of asking could not be intuitively linked to the presenting complaint, or seen as aiding in the treatment of illness. These reservations were often in notable contrast to the opening responses.

I think a GP has to make a call whether they believe they need to know, in any one case, whether they need to know that information. So, you know, if you’ve gone [be]cause you’ve got a cold, then it probably is irrelevant … – P16

Participants reported that they would feel surprised, confused or misunderstood if alcohol assessment were conducted with no attempt to connect it with the presenting complaint, or where the purpose for the enquiry was not explicitly contextualised. However, context could be provided by GPs asking questions within the SNAP framework:

I guess if you had the other questions about other lifestyle factors it would provide context. It would set the lifestyle scene to insert the alcohol question … kind of, ease you into it … – P22

Approach and language of the alcohol enquiry

The dynamics of the interaction that occurred between the patient and doctor influenced the acceptability of alcohol enquiry. The language used and lead-in were perceived to be important. Participants reported a preference for GPs who were seen as caring and tactful, used a friendly tone, and provided a relaxed atmosphere. Forcefulness in the dialogue was seen as disrespectful by some participants. Forcefulness could damage the doctor–patient relationship, foster patient mistrust and result in defensive behaviour.

I found that the doctor that I was put in with at the time, she was – oh, how do I say it – very sort of forceful, punching forward with questions, and this was the first time that I had ever seen her, right. And I thought, ‘No, I don’t want to talk to you because I don’t know you and I don’t like the way you are talking to me’ … – P2

Participants seemed to enjoy being part of the conversation when it was collaborative (ie interactive, shared decisions). Building the alcohol discussion around shared problem-solving might create purpose and relevance to the dialogue, while also fostering a sense of partnership and trust.

Well, I think so much has changed because the service now from a GP is much more patient-oriented. It’s not doctor dictating and patient, you know, listening. It’s a more inclusive relationship … A very different style of doctoring, and you can sort of equate that to the way teaching’s changed as well to be more student-centred rather than teacher-centred. – P15

The ‘narrative’ of the consultation – the sequence of events building towards the commencement of alcohol enquiry – was important. Participants indicated that they wanted their primary concerns to be addressed first, with other issues addressed later, with negotiation.

I would expect that they primarily are treating the issue that I have come in to see them about, but if they then said, you know, ‘As part of our general ongoing healthcare of patients, we always ask these particular questions’, then I think I would be fine with that. – P4

Unease regarding the moral dimension of alcohol consumption

Most participants conceptualised drinking alcohol as an activity with a moral dimension. The uncertainty of how a GP might respond in a consultation regarding alcohol consumption resulted in feelings of apprehension. Participants reported that they would answer alcohol questions with caution, especially if the GP was perceived to be judgemental.

There’s an opinion that it’s not a disease, that it’s a moral issue, and that if people had enough willpower or would get their act together then they would get well. And … some GPs don’t have any tolerance for alcoholics. They’re seen in a bad light and not as people that need help … I’ve had a fear of being honest until I know what their response is going to be. – P7

Being regarded as an ‘alcoholic’ was seen as socially unacceptable by the participants. The fear of being labelled as an ‘alcoholic’ appeared to be an important subtext in the interactions between patients and GPs. Some participants stated that receiving alcohol enquiry from the GP could be viewed as an insinuation that they had a drinking problem. They also revealed that feelings of shame over their drinking behaviours decreased the acceptability of alcohol enquiry, and even lead them to underreport.

I may bend the truth. I think we’re all a little bit embarrassed about it sometimes, the amount that we may drink. So … you may ask me a question now of how often … how much do I drink, to which I might reply ‘two glasses a day’ … – P11

Some participants felt that trust in an established doctor–patient relationship allowed them to communicate safely and honestly.

I think … that [with a] new GP … if I was to reply honestly about how much alcohol I consumed, personally, I would feel like they may think that that was a little too much. So I would probably, maybe, reduce it a little in my response. Whereas, with my relationship with my doctor that I see all the time, I feel … I’ve become a little more honest because I feel like they have much more of an interest in helping me to maintain my health and wellbeing. – P20

However, others commented that the lack of familiarity with a new GP allowed for a more open exchange as no prior perceived judgements had been formed about the patient’s morality.

I can imagine myself wanting … [my regular] doctor to see me positively … but to a stranger it’s often easier to … admit that you’re doing something … – P22

Discussion

Positive patient attitudes towards the role of GPs conducting health promotion have been well described,19–21 but these might not translate to individual consultations.11 When asked to elaborate about their beliefs and attitudes towards having alcohol discussions with GPs, our participants had important reservations when it came to engaging in alcohol discussions. This was despite their general positive beliefs of health promotion, which was consistent with prior qualitative research on patient beliefs.13 The acceptability of alcohol dialogue appeared to be governed by its perceived relevance, which in many participants was determined by whether the presenting complaint was seen to be an issue affected by alcohol drinking. That enquiry, which is more acceptable when there is an understood conceptual link between the current health problem and alcohol, has been previously identified in research of patients13,22 and GPs.23

Australian GPs have previously expressed that alcohol enquiry could be perceived as a threat to the doctor–patient relationship.10 Our results indicate that these concerns relating to the approach and language of consultation, and the interactional dynamics between patient and doctor, are likely to be well founded. This accounts for the observation that while developing rapport12 and using humour24 might foster favourable outcomes, non-patient-centred screening approaches could result in negative reactions from patients.25

GPs have reportedly been worried about being perceived as judgemental,10,23,26,27 and this is well aligned with our findings of patients’ fears of being judged. The moral nature of alcohol consumption and health, and the ongoing social stigma of problem drinking, have been recognised by patients12,13 and GPs.10,26 Our participants have confirmed previous GPs’ perceptions that patients might not be truthful with their alcohol use when probed,10,25 demonstrating the risk of assessment approaches that are not seen as acceptable.

We propose that our three-factor model may indicate how alcohol enquiry, and hence early detection strategies, can be implemented in ways that are acceptable to patients.

First, attention must be given to patients’ perceptions of alcohol dialogue relevance. Although they may be very acceptable (and thus an opportunity) in certain presentations (eg diabetes), alcohol questions may be seen as unimportant in others (eg low back pain).15 Establishing a clear context for the enquiry – for example, within a health promotion framework, such as asking within SNAP15 or as part of a structured health screening approach28,29 – might improve acceptability.

Second, we need to be respectful of the beliefs and attitudes that patients and GPs have towards their relationship, and recognise the morally charged nature of alcohol discussions. The subtleties of interpersonal ‘face work’ in preserving doctor–patient relationships30 are important in the broader context of general practice care and should be acknowledged as such. Early detection strategies that require the rigid adoption of alcohol-screening questions within general practice consultations are unrealistic and possibly inappropriate, and thus unlikely to be successful. Newer implementation approaches such as electronic waiting room screening,28 which can help establish the context of alcohol discussions prior to the consultation, and GP-facilitated internet interventions,29,31,32 which can allay the discomfort and barriers to having alcohol discussions within the consultation room, should be further studied.

Strengths and limitations

This study was designed to augment the results from an earlier survey experiment.15 By using a grounded theory approach, we were able to construct a model that provided explanatory richness to those findings, and might also provide a framework for guiding the implementation of acceptable early detection strategies. We were able to purposively sample participants with a broad range of demographic features.

However, an important limitation was that this study was based at a single centre. As two of the investigators were practising clinicians at the clinic, participants may have been biased toward giving socially desirable answers to maintain the doctor–patient relationship, despite being informed that they would be de-identified. Our sampling was further limited to those who responded to the initial survey experiment – it is doubtful whether the participants are representative of the study site. Moreover, our participants tended to be well educated, and born in Australia or another English-speaking country. It is unclear how well our model would perform in patients from diverse cultural backgrounds, with different beliefs toward alcohol and health.

One-quarter of Australian residents are born overseas, and migrants account for over two-thirds of the population in some neighbourhoods.33 The perspectives of patients who are not from ‘temperance’ drinking cultures (Western and Northern Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand)34 are mostly unknown.11 This represents a major evidence gap that is relevant to contemporary, multicultural Australian society, and one that needs to be urgently explored.

Implications for general practice

- The acceptability of alcohol questions for patients in general practice consultations can be understood using a three-factor model.

- Framing the context of the alcohol assessment, such as by linking the dialogue to the presenting complaint, using collaborative consultation styles and respecting patient sensitivity, may improve acceptability.

- It should not be assumed that patients will find alcohol early detection strategies in general practice to be acceptable – consultation contexts matter.

Authors

Chun Wah Michael Tam BSc(Med) MBBS MMH(GP) FRACGP, Staff Specialist in General Practice, Fairfield Hospital – General Practice Unit, Prairiewood, NSW; Conjoint Senior Lecturer, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW. m.tam@unsw.edu.au

Louis Leong, medical student, Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

Nicholas Zwar MBBS MPH PhD FRACGP, Professor of General Practice, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

Charlotte Hespe MBBS(Hons) DCH GCUT FRACGP FAICD, Head General Practice Research and Conjoint Head, School of Medicine, General Practice, University of Notre Dame Australia, Darlinghurst, NSW

Competing interests: Chun Wah Michael Tam, Nicholas Zwar and Charlotte Hespe’s institutions received a Family Medical Care, Education and Research Grant 2013 from RACGP in relation to this work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in the study. We especially acknowledge Ms Jacqui Ellsmore and Ms Wendy Liu for logistical support at the general practice, and Ms Sarah Jacob for organisational support of the project. This project was funded by an RACGP Family Medical Care, Education and Research Grant, and the authors gratefully acknowledge the RACGP Foundation for their support.