Supervision has been defined as ‘the provision of guidance and feedback on matters of personal, professional and educational development in the context of a trainee’s experience of providing safe and appropriate patient care’.1 It comprises two distinct but closely related elements – facilitated learning (educational supervision), and monitoring quality of care and patient safety (clinical supervision). Patient safety is the cornerstone of high-quality care, and monitoring this is the key aspect of clinical supervision.2

Vocational general practice training in Australia is based on the so-called ‘apprenticeship model’, where registrars consult independently with patients, but practise under the supervision of accredited general practice supervisors. A general practice supervisor has been defined as ‘a general practitioner who establishes and maintains an educational alliance that supports the clinical, educational and personal development of a registrar’.3 While regional training providers (RTPs) have a significant role in coordinating and delivering training, the vast majority of the registrar’s teaching and learning occurs in the practice under the guidance of the supervisor. The general practice supervisor is rightly regarded as providing the cornerstone of training.4

It follows that one of the foundations of a high-quality general practice training program is the delivery of relevant, evidence-based, high-quality educational continuing professional development (EdCPD) for general practice supervisors.5 This is reflected in The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) Vocational training standards,6 which addresses the educational and training requirements for general practice supervisors. It states that supervisors must participate in regular quality improvement and professional development activities relevant to their role. The standards have a requirement for supervisors to attend scheduled meetings each year in order to enable them to develop teaching skills. Likewise, the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine’s (ACRRM’s) Standards for supervisors and training posts7 states that supervisors must participate in ‘supervisor training and other activities to further develop teaching/mentoring skills. This involves attendance at supervisor or teacher training’.

Current EdCPD for general practice supervisors

In general, outcomes-based medical education, and curriculum planning and development are inextricably linked.8 More specifically, the curriculum has been described as critical to the effectiveness of educational change in faculty development.5 The general practice training environment is unique, and existing generic clinical supervision curricula have been described as inadequate to support specific general practice supervisor EdCPD.9,10

Internationally, there has been a call for a system-wide approach to clinical teacher training in competency-based medical education.11 Frameworks for EdCPD exist for general practice supervisors (trainers) in countries such as Europe12 and Canada.13 In Australia, guidelines and a syllabus have been developed for the supervision of prevocational trainees.14 However, despite the requirement for an Australian general practice supervisor EdCPD, there is no standardised approach to guide the delivery of this highly specific training. While a curriculum framework for Australian general practice supervisor training that contained broad goals and objectives was previously developed,15 it did not include specific content and was never formalised by the RACGP or ACRRM, and consequently not widely adopted.

EdCPD in Australia has been the primary responsibility of RTPs and varies in content across regions.4 Anecdotally, the training of supervisors has often been ad hoc and disconnected. There are many other providers of supervisor education and training, including universities,16 colleges, ‘Teaching on the Run’,17 General Practice Registrars Association (GPRA)18 and General Practice Supervisors Australia (GPSA).19 Although this breadth of providers may provide choice and diversity of instructional methods, there has previously been very little coordination in the development of content, or a common core curriculum.

A number of other factors have the potential to impact on the development, delivery and uptake of high-quality EdCPD. These include regional geography, local expertise and resources. As well, financial and time pressures can influence a supervisor’s availability and motivation to attend EdCPD. General practice supervisors have limited time for professional development, and much of this is taken up with maintaining clinical practice currency.

Australian general practice training currently faces a period of significant uncertainty with the recent dissolution of General Practice Education and Training (GPET), the national body previously responsible for overseeing the Australian General Practice Training Program, and the appointment of new regional training organisations. These change pose a risk of erosion of the existing fledgling collaborative arrangements for development and delivery of GP supervisor EdCPD.

Table 1. Suggested EdCPD curriculum content

|

|

Topic areas

|

Linked activity or skill

|

|---|

|

Foundation modules

Roles and responsibilities

Learning in the practice

Formal teaching

Ad hoc teaching

Assessment, monitoring and feedback

Organisational induction

|

Supporting the development of a learning plan

Developing a plan for a teaching session

Using WWW-DOC47

Directly observing and giving feedback on a consultation

|

|

Building modules

Communication skills

Conflict resolution

Consultation analysis and assessment

Patient safety

Formative assessment

Summative assessment

Professionalism

Clinical reasoning

Critical thinking and evidence-based medicine

Cultural safety training

Registrar in difficulty

Critical incident

Highly performing registrar

Vertical integration

Quality practice

Practical procedures

Quality improvement

|

Active listening

Defusing a conflict scenario

Rating the consultation using a tool

Random case analysis of clinical records

Giving feedback (eg mid-term feedback)

Writing an Objective Structured Clinical Examination

(OSCE) case

Supporting reflective practice (eg using patient satisfaction tool)

Learning from case discussion

Critical appraisal of a journal article

Culturally safe consulting

Diagnosing the learner

Debriefing a medical error

Analysing learning needs

Teaching multiple learners

Reviewing test ordering practice by inbox review

Teaching a procedural skill

Planning a clinical audit

|

Emerging issues for general practice supervisor EdCPD

The RACGP’s Vocational training standards is explicitly underpinned by the need for high-quality training of Australian GPs, with a strong emphasis on patient safety.6 Vocational training programs need to base general practice supervisor EdCPD programs on best practice and the available evidence to help meet this need. There are a number of emerging issues in general practice training, with significant implications for future EdCPD.

Clinical supervision issues

A number of recent studies have significantly enhanced the understanding of the Australian GP training landscape, as follows. Clinical exposure of registrars has recently been described and found to differ substantially from established GPs, including lower rates of encounters with older patients and less chronic disease management.20 The rate, nature and value of registrar information-seeking and advice-seeking from the supervisor have been examined, with significant implications for learning and patient safety.21,22 The role of the general practice supervisor has been re-defined and better described, including the critical importance of the registrar–supervisor educational alliance.3 The motivators for GPs undertaking the supervision role, and the frequency and types of supervision activities undertaken, have also been better described.23 As well, the indicators of ‘quality teaching practices’ have been outlined, particularly the contribution of high-quality supervision.24

Structural issues

There are well-documented capacity constraints on the placement of general practice registrars into Australian practices, which are likely to worsen with the increasing numbers of trainees and retirement of supervisors.25 These have led to a variety of new models on the delivery of supervision, including enhanced vertical integration,26 shared learning27 and non-traditional supervision such as consultant on call,28 registrars as teachers29 and supervision teams.25,30 As well, practice-based, small-group learning (PBSGL) models of EdCPD have been described as potentially being another new model.31 These models have generally been favourably evaluated, but further refinement, implementation and evaluation requires general practice supervisor EdCPD that provides appropriate training in the requisite knowledge and skills.

Educational issues

The RACGP’s Vocational training standards has an increased emphasis on general practice supervisors assessing and monitoring their registrars’ competence, and matching this to an appropriate level of supervision.6 The term ‘clinical oversight’ describes specific patient-care activities performed by supervisors to ensure quality of care.32 Concerns regarding the accuracy of supervisors’ assessments have been raised.33 The development of skills and confidence in clinical oversight requires appropriate training, particularly in using newly developed, validated tools for assessing competence such as Entrustable Professional Activities.34

Other issues

There are other emerging themes that need to be considered in future EdCPD. There is an increasing emphasis on reflective practice in medical education.35 Reflective practice forms part of self-regulation, a deliberate process of professional development and lifelong learning.36 Other issues include supervision of different learners (eg the ‘struggling’ trainee,37 the ‘high-performing registrar’38 and international medical graduates39), and teaching of specific content (eg care of older patients40 and multimorbidity,41 cultural competence,42 collaborative care,43 professionalism,44 and critical thinking and research skills45). All of these need to be represented in any future EdCPD program.

Structured EdCPD curriculum for general practice supervisors

There has been a call for faculty development programs to respond to changes in medical education and healthcare delivery, and to adapt to changing roles.5 In many ways, it is therefore an opportune time for the development of a structured, best-practice, competency-based curriculum for Australian general practice supervisors.

A national general practice supervisor core curriculum would provide standardisation across all training providers, and help ensure comprehensive, cost- and time-effective, high-quality training for new and existing supervisors. Furthermore, it would encourage (and require) broader collaborative input into its development and implementation, incorporate emerging content and structural issues, and avoid duplication of effort across multiple regions. In particular, such development would bring together multiple stakeholders, including registrars (and the GPRA), supervisors (and the GPSA), patients, medical educators (and RTPs), academics and colleges.

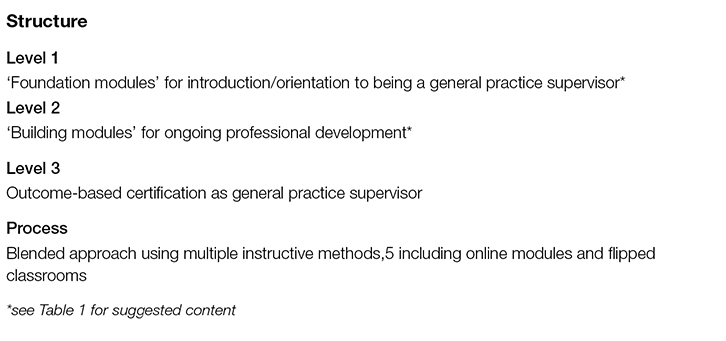

A national curriculum should continue to embrace the parallel elements of the general practice supervisor’s role, namely educational and clinical supervision, and have an explicit focus on patient safety. An approach to a possible draft curriculum, including possible topics, is described in Figure 1. Elaboration of content areas must be informed by a comprehensive analysis of general practice supervisors’ EdCPD needs. As well, it is critical that the common general practice supervisor EdCPD curriculum allows sufficient scope for adaption to reflect regional needs – for example, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health or procedural skills training.

|

| Figure 1. Possible approach to general practice supervisor EdCPD |

A future Australian general practice supervisor EdCPD program should focus on developing core competencies, in recognition of each supervisor’s diverse pre-existing knowledge, skills and experience, and their individual pace of, and engagement with, learning. However, we recognise the hazards of a reductionist approach to competency-based training, which potentially fragments outcomes into artificially discrete entities. We therefore support a continued focus on the higher-order skills and key elements within such competencies.46 This includes continuing to apply the more traditional elements of EdCPD, namely experiential learning, peer relationships, and opportunities for face-to-face teaching, feedback and assessment.

As well, any future general practice supervisor EdCPD program must include a rigorous evaluation process and contribute to the relatively limited evidence base in vocational general practice training. This could be overseen by a collaborative group responsible for development, evaluation and curation of resources and modules, equivalent to the American Society of Teachers of Family Medicine or the UK-based Academy of Medical Educators.

We acknowledge the many potential barriers to the implementation of a national standardised curriculum, for both supervisors and RTPs. We believe there is a need for the development of benchmarking processes for current general practice supervisors, and appropriate recognition of prior experience and learning.

Conclusion

Although the current changes to general practice training pose risks and uncertainty, these also provide opportunities for rekindling a collaborative approach to general practice supervisor EdCPD. We recommend the development of a core curriculum for general practice supervisors that is competency-based and incorporates evidence for effective supervision. This will help to ensure ongoing, high-quality general practice training and respond to the changing landscape of Australian general practice.

Authors

Simon Morgan MBBS, FRACGP, MPH&TM, General Practitioner, Medical Educator, GP Training Valley to Coast, Mayfield, NSW. simon.morgan@gptvtc.com.au

Gerard Ingham MBBS, FRACGP, DRANZCOG, General Practitioner Supervisor, Medical Educator, Springs Medical Centre, Bendigo, VIC; Beyond Medical Education, Bendigo

Susan Wearne BM MmedSc, FRACGP, FACRRM, DCH, DRCOG, DFFP, GCTEd, General Practitioner, Central Clinic, Alice Springs, NT

Tony Saltis MBBS, FRACGP, DRANZCOG, General Practitioner, Medical Educator, GP Training Valley to Coast, Mayfield, NSW

Rosa Canalese MBBS, Dip Paed, FRACGP, MPH, General Practitioner, Director of Training, GP Synergy, Sydney, NSW

Lawrie McArthur BMed, MBBS, FACRRM, FRACGP, DRANZCOG, General Practitioner, Director of Training, Adelaide to Outback GP Training Program, North Adelaide, SA

Competing interests: Susan Wearne from September 2012 to December 2014 was Supervisor Research and Development advisor at GPET. She worked on earlier drafts of this article during her employment with GPET. She has also been funded to deliver GP supervisor training, receives royalties for the book Clinical Cases for General Practice Exams and undertakes contract work reviewing materials on gplearning.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, peer reviewed.