Urticaria is characterised by swelling of the skin and mucosa due to plasma leakage.1

The term is often used to describe a rash that may present with weals, with or without angioedema. Urticaria can be divided into a number of subgroups listed below:

- ordinary urticaria

- acute urticaria

- chronic urticaria

- urticarial vasculitis

- physical urticaria.

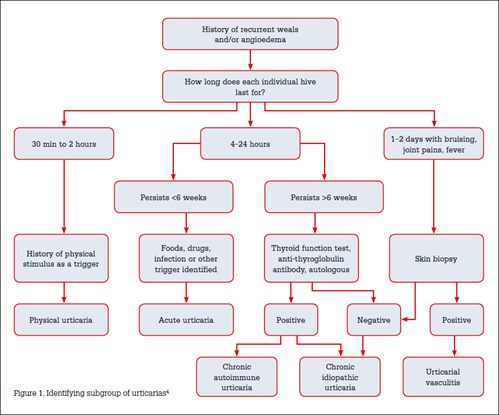

These subgroups are differentiated by the time frame, clinical presentation and triggers of the uriticarial rash (Figure 1).2 The focus of this article is on chronic urticaria, which is a chronic relapsing skin disease characterised by highly pruritic weals that persist for less than 24 hours and recur on a daily basis for more than 6 weeks.3 Some consider urticarial vasculitis to be a chronic urticaria; however, the term chronic urticaria commonly refers to an ordinary urticaria. Chronic urticaria can have a negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, affecting social function and emotional wellbeing.2

Evaluation and diagnosis of chronic urticaria

History

A detailed history is usually sufficient to establish a diagnosis of urticaria and the type of urticaria. Chronic urticaria persists for more than 6 weeks. An urticaria that lasts less than 6 weeks is an acute urticaria in which the characteristic weals may last less than 24 hours. If a patient describes a history of individual lesions lasting more than 24 hours, then vasculitic urticaria should be considered. For patients who are unable to estimate the time frame of the lesion, drawing around a new lesion and then recording how long this takes to disappear can be useful.

Patients report weals that are associated with itch, often worse at night. This pruritus can be debilitating enough to affect activities of daily living and quality of life. For patients who have difficulty describing symptoms (eg after the symptoms have resolved), it is often useful to show patients photographs of urticarial lesions. Table 1 outlines a number of history questions that may be relevant.

Medication history is particularly important. Urticaria can be caused by a number of medications including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, antibiotics, antidepressants, antihypertensives, antifungals, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors. Urticaria can appear many months to years after starting the medications.

In 80–90% of cases no identifying trigger for chronic urticaria can be established.4 However, it is thought that many of these idiopathic urticarias may be attributed to autoimmune causes. Chronic urticaria is associated with autoimmune disorders, most commonly hypothyroidism, but also coeliac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and type 1 diabetes mellitus.5,6 History taking could also focus on excluding these diseases. Patients with autoimmune chronic urticaria have been found to have a more aggressive disease course and are resistant to treatment.7 There are some less clear associations between chronic urticaria and malignancy. Urticarial vasculitis is, however, associated with malignancy.8,9, Associations of chronic urticaria with Helicobacter pylori and Candida infections are not well substantiated.10

Table 1. History questions

|

1. Signs and symptoms associated with lesion Pruritis/burning sensation Duration of individual lesions Length of time that ongoing lesions have been occurring Accompanying angioedema Associated systemic signs and symptoms including fever, weight loss, joint pain, abdominal pain.*

|

|

2. Identifying triggers Newly administered drugs Antibiotics Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) Hormones

|

|

3. Aggravating factors Physical stimuli† (eg heat/tight clothing, cold/heat) Alcohol Stress Food (food allergies are a rare cause of chronic urticaria; however, some foods, for example spicy foods, aggravate symptoms. )

|

|

4. Atopy

|

|

5. Past medical history and changes to health

|

|

*To exclude differential diagnosis †If physical factors are the main trigger then consider a diagnosis of physical urticarial syndrome.

|

|---|

Physical assessment

Urticaria presents as pink or white well-circumscribed, raised weals surrounded by an erythematous base and central pallor. These weals may become confluent, forming large plaques. Urticarial lesions may vary in size and shape, ranging from annular to serpinginous outlines, and ranging from lesions that are millimetres to a few centimetres in size. Morphology of these weals may help distinguish between physical urticarias and other subgroups of urticaria. Weals may be accompanied by angioedema, which is non-pitting asymmetric swelling that may affect the lips, cheeks, limbs, genitals and periorbital area.

Differential diagnoses to consider

There are a number of underlying diseases that may present with urticaria. Consider SLE, where fever, weight loss and arthritis occur concurrently. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (eg Muckle-Wells syndrome) are genetic inflammatory diseases that may present characteristically with periodic urticaria, fever, conjunctivitis and muscle and skin sensitivity. They may also be associated with sensorineural hearing loss and arthritis.11 Conditions that may present with skin eruptions that mimic urticaria are outlined in Table 2. The clinical history and physical examination findings may provide clues to these differentials. A skin biopsy can be performed if the diagnosis is in question.

Table 2. Conditions that may mimic chronic urticaria

|

|

Disease

|

When to consider the diagnosis

|

|---|

|

Urticarial vasculitis

|

Hives are painful (not pruritic) Hives last more than 48 hours Residual bruising or pigmentation occurs after resolution of hives May have symptoms like fever, chills, arthralgias May have previously had another systemic inflammatory disease

|

|

Cryoglobulinemia

|

Lesions over buttocks and lower extremities. May occur in patients with hepatitis B/C

|

|

Mastocytosis

|

Lesions occur with very mild physical trauma, for example light touch

|

|

Polymorophic eruption of pregnancy

|

Occur in pregnant patients Presents within abdominal striae Does not affect periumbilical area Sparing of face, palms, soles

|

Investigations

Normally, laboratory investigations are not required in the diagnosis of chronic urticaria and most investigations will be normal. A list of suggested investigations to rule our other differential diagnoses is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Suggested investigations

|

|

Test

|

Findings

|

|---|

|

FBE

|

Usually normal in chronic urticaria If there is eosinophilia – further investigation for atopic disorder or parasites should be performed.

|

|

CRP/ ESR

|

Usually normal in chronic urticaria May have mild elevation of ESR If there is a significant elevation in either CRP/ESR then consider investigation for systemic diseases/urticarial vasculitis. Further tests include cryoglobulins, hepatitis B/C serology, liver function tests

|

|

Thyroid function tests and thyroid antibodies

|

perform in patients who are unresponsive to antihistamines

|

|

ANA

|

Can be raised in patients with autoimmune diseases.

|

|

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FBE, full blood examination

|

|---|

Autologuous serum skin test

At present, an autologous serum skin test (ASST) is the most useful test for investigating chronic urticaria and has a reported 81% sensitivity and 78% specificity.12 Currently, this test can only be performed by specialists. It is used to determine whether a patient may have a good response to immunomodulatory treatments.13

The procedure involves drawing a sample of blood from the patient during a flare. The blood is then separated by centrifugation to form serum. A small amount of the serum is then injected into unaffected skin on the forearm. At the same time equal amounts of normal saline and histamine are injected on the same forearm. The response at 30 minutes is then recorded. A weal of >1.5 mm at the site where the serum was injected is considered a positive response. A weal larger than the saline-induced response is also considered positive. Poor injecting techniques and administration in dermographic patients may elicit a false-positive result. The ASST has a role in determining the prognosis of a patient with chronic urticaria. A positive ASST test also correlates with the duration of the disease and the severity of the urticaria.13

Role of skin prick testing

Skin prick testing (SPT) is a procedure where a small sample of allergen is introduced into the patient’s skin by pricking the skin, to induce an allergic response. SPT is not usually indicated in patients with chronic urticaria, as a positive finding is not always clinically useful. A study examining 88 patients with food and aero-allergies found that, of the patients with positive SPT for food allergens, only 34.6% had clinically relevant food-induced urticaria.14 Furthermore, another study by the same author examined 172 patients for house dust mite allergies and found that 34.9% of patients with chronic urticaria had a positive test but this was only relevant in 3.3% of cases.4

Skin biopsy

Skin biopsies are not usually performed in chronic urticaria. However, if the diagnosis is in question, particularly if there is suspicion of urticarial vasculitis, then a biopsy can be performed. Table 4 outlines the indications for a skin biopsy.

Table 4. Indications for a skin biopsy

|

|

Lesions occurring for more than 24 hours Painful urticarial lesions Petechia or purpural lesions associated with urticaria Elevated CRP/ESR Systemic symptoms Unresponsive to antihistamines. Features of mastocytosis (flushing, diarrhoea, syncope, abdominal cramping)

|

Treatment

Patients should be educated on avoiding trigger factors and aggravating factors. The natural history and progression of the disease should also be discussed. Avoidance of NSAIDs and ACE inhibtors should be encouraged. Non-medicated lotions such as menthol in aqueous cream can alleviate symptoms.

First-line therapy

Histamine H1 receptor antagonists

Histamine H1 receptor antagonists have been shown to reduce symptoms of hives and pruritus. These agents should be taken once daily. Not all patients will respond completely to H1 receptor antagonists. About 60% of patients with chronic urticaria respond to H1 receptor antagonists.15 If the patient fails to respond then another H1 receptor antagonist can be trialled. H1 receptor antagonist doses should be maximised before trialling other therapies.

First-generation H1 receptor antagonists, including hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine and cyproheptadine, can cause anticholinergic side effects and sedation. These side effects make the first-generation H1 receptor antagonists useful for patients who have insomnia secondary to pruritus. Second-generation H1 receptor antagonists, including cetirizine, loratadine, levocetirizine and desloratidine are equally effective and do not have the sedative and anticholinergic effects. For this reason they are the mainstay of treatment.

Histamine H2 receptor antagonists

Histamine H2 receptor antagonists, including cimetidine, ranitidine and nizatidine, can be used in conjunction with H1 receptor antagonists. They are not generally used alone.

Second-line therapy

Corticosteroids

Short-term use of corticosteroids is reserved for symptoms that are severe and cause significant pain and distress. Complete resolution of symptoms occurs very quickly. The use of corticosteroids is controversial because patients often have relapses after cessation of corticosteroids. Long-term use is not indicated because of the side effects of hypertension, hyperglycaemia, weight gain, osteoporosis and peptic ulcers.

Doxepin

Doxepin is a tricyclic antidepressant with potent H1 and H2 receptor antagonist activity.15 It is used at a doses of 10–30 mg/day for chronic urticaria; however, dosage can be increased if patients are treated concurrently for depression. Doxepin can cause sedation and is usually taken at night. Doxepin is subsidised through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and may be the only affordable option for healthcare card holders. Mirtazepine, another antidepressant, has been shown to reduce symptoms of pruritis because of its effects on the histamine H1 receptors.

Narrowband ultravoiolet B light

Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) is used in a variety of skin ailments because of its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. NB-UVB may be useful in patients with chronic urticaria. In an unblinded study examining 81 patients, 33 control patients were given H1 receptor antagonists and 48 patients were treated with NB-UVB and H1 receptor antagonists.16 Urticarial symptoms were reduced in both groups but the urticarial activity was significantly lower in the NB-UVB/H1 receptor antagonist group.

Third-line therapy

Cyclosporine

There are numerous reports in the literature detailing the efficacy of cyclosporine. One study showed that more than one-third of patients stayed in remission after cessation of cyclosporine and a further one-third had only a mild relapse.17 Side effects include hypertension and renal toxicity. Patients with chronic urticaria require a private prescription.

Other medications

There is evidence that medications including dapsone, intravenous immunoglobulin and methotrexate are useful treatments for chronic urticaria; however, only uncontrolled case studies have been published.

Emerging therapies

Omalizumab

Omalizumab is an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, which has been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Its main mechanism of action is by reducing free IgE levels. A number of phase III trials have been published showing its superior results when compared with H1 receptor antagonists.18,19 A recent phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examined the use of omalizumab in 336 patients.20 Patients received either 300 mg subcutaneous omalizumab (n = 252) or placebo (n = 84). After 12 weeks there were significant improvements in pruritus, number of hives, size of hives and days without angioedema.21 However, after cessation of omalizumab symptoms reccurred.

Autologous serum and autologous whole blood therapy

Autologous serum is a promising treatment, which has been shown to be useful in the treatment of severe urticaria. As with the process of ASST, the patient’s blood is collected and centrifuged to produce a serum. This serum is then injected intramuscularly every fortnight for 8 weeks. Results have been particularly promising for patients who are ASST-positive.

Similarly, the efficacy of autologous whole blood (AWB) injections has been described in the literature.21 One placebo-controlled trial examining 56 patients showed that AWB treatment improved the number, size and duration of symptoms in patients with chronic urticaria who were ASST-positive.21

A recent study by Kocaturk et al22 showed conflicting evidence suggesting that AWB and autologous serum injections had no superiority over a placebo in a study consisting of 88 patients with chronic urticaria.

Key points

- Diagnosis of chronic urticaria can be established with a history and physical examination.

- An alternative diagnosis should be considered in the context of accompanying symptoms.

- Histamine H1 receptor antagonists are the mainstay of treatment.

- Patients who are unresponsive to treatments should be referred to a specialist for alternative treatment options.

Competing interests: Rodney Sinclair received payment from Novartis for travel, accommodation and meeting expenses relating to attendance at an overseas meeting on urticaria.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.