The number of learners requiring placement in Australian general practice is unprecedented. The number of general practice registrars-in-training increased by 98.7% between 2003 and 2009,1 and the annual intake was projected to increase by 71% between 2010 and 2014.2,3 The Prevocational General Practice Placement Program (PGPPP) has also created additional demand for junior doctor placements.4 Lastly, universities have increased the number of medical students being placed into general practices.5 This is creating pressure on general practitioner supervisors (GPSs), when considered in the context of an ageing workforce.6

Shared learning is a teaching model that may help to ameliorate general practice training capacity constraints through reduced supervisor workloads.7 We define shared learning as a planned teaching session involving more than one learner at different stages of training. This may include general practitioner registrars (GPRs) at different levels.

Research to date about shared learning in general practice has come from qualitative studies in Australia, Britain and Ireland,8–12 and suggests that shared learning may encourage collegiality and improve the quality of learning. Other proposed benefits include more efficient use of physical space,13 enhancement of the teachers’ learning, increased teamwork and morale, increased collegiality between learners and GPSs8 and the opportunity of achieving a critical mass in smaller centres.12

Reported barriers to shared learning include losing personalised one-to-one teaching time especially in remedial situations, maintaining teaching quality and the effectiveness of learning, difficulty in managing small group dynamics and difficult learners, balancing disparate learning needs and increased stress for supervisors.8

This project sought to collect quantitative data on shared learning in general practice using a national survey to provide information that is generalisable across the Australian general practice training environment. The study examines stakeholders’ attitudes to shared learning, their views on whether shared learning can address capacity constraints and what they see as the key barriers to and facilitators of this model, as well as providing a snapshot of current practice.

Methods

Recruitment and data collection

GPSs, GPRs, PGPPP trainees and medical students were recruited to participate in an online survey via invitations in electronic newsletters and emails sent by 10 regional training providers (RTPs) to members of the:

- National GP Supervisors Association

- General Practice Registrars Association

- General Practice Student Network.

In order to increase completion rates, participants could enter a draw for an iPad. Several reminder emails were also sent. Given the number of GPSs, GPRs and PGPPP trainees involved in GP training in 2010,14 346 GPSs, 333 GPRs and 123 PGPPP trainees were needed to obtain a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5. A sample size of 200 was estimated for medical students in the absence of specific numbers present in general practice. Ethics approval was obtained from Southern Cross University’s Ethics Committee (ECN-12-276).

Instrument development

A shared learning scale was developed to measure attitudes to shared learning. The survey also examined demographics, current shared learning practices and participants’ views on the barriers to and facilitators of shared learning using fixed response questions. Additional opportunities for comments were provided throughout the survey. Survey items were informed by several qualitative studies on shared learning8–12 and review by an expert reference group encompassing medical educators and stakeholder groups. Separate questionnaires were developed for supervisors and learners. Two to four cycles of review and piloting by samples of 17 supervisors and 30 learners were used to validate the questionnaires. A further review of scale reliability was conducted on a subsample of 114 PGPPP and GP surveys. Cronbach’s alpha on this subsample ranged from 0.74–0.90 (adequate to excellent).15

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated on survey items. Cronbach’s alpha and item-to-total correlation statistics were calculated on scales. Chi square tests examined differences in proportions. An independent samples t-test examined differences in group means when two groups were examined and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when more than two groups were examined.

Results

Responses were obtained from 1122 participants. On the basis of 2010 data, our respondents represented about 14% and and 7% of nationally registered GPSs and GPRs respectively. The sample demographics are outlined in Table 1. Cronbach’s alpha on the shared learning scale was 0.81–0.86.

Table 1. Sample demographics

|

|

Group

n = 1122

|

Stage

|

Age range (years)

|

Gender (national)

|

Locality (national)

|

Mode

|

|---|

|

GPSs

n = 269

|

Supervisor

<5 years: 23%

5–10 years: 22%

≥10 years: 54%

|

<30: –

30–39: 8%

40–9: 28%

50–59: 48%

≥60: 16%

(mean age GPs nationally = 51)16

|

F: 41% (GPs 41%)16

M: 59% (GPs 59%)

|

Rural: 59%

Urban: 39%

Remote: 3%

|

FT: 74%

PT: 26%

|

|

GPRs

n = 221

|

GPT1: 34%

GPT2: 13%

GPT3: 29%

GPT4/ES: 24%

|

<30: 32%

30–39: 48%

40–49: 15%

50-–59: 4%

≥60: 1%

(mean age nationally = 35)17

|

F: 68% (64%)17

M: 32% (36%)

|

Rural: 52% (52%)18

Urban: 44% (44%)

Remote: 4% (4%)

|

FT: 75%

PT: 25%

|

|

PGPPPs

n = 319

|

PGY1: 31%

PGY2: 29%

≥PGY3: 40%

|

<30: 72%

30–39: 22%

40–9: 5%

50–9: 1%

|

F: 66%

M: 34%

|

Rural: 51% (51%)18

Urban: 38% (34%)

Remote: 11% (15%)

|

FT: 96%

PT: 4%

|

|

MSs

n = 313

|

Year 1: 2%

Year 2: 15%

Year 3: 27%

Year 4: 28%

Year 5: 19%

Year 6: 9%

|

<30: 89% (86%)19

30–39: 8% (12%)

40–49: 2% (2%)

50–59: 1%

|

F: 71% (55%)19

M: 29% (45%)

|

Rural: 43%

Urban: 53%

Remote: 4%

|

FT: 99%

PT: 1%

|

|

National comparison data in brackets where available

FT, full time; PT, part time; GPSs, GP supervisors; GPRs, GP registrars; PGPPPs, junior doctors in general practice;

MSs, medical students

|

|---|

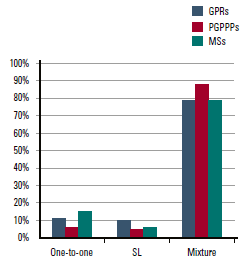

| 88% of GPSs had multiple levels of learners (MLL) in their practice. Compared with urban supervisors, a higher proportion of rural supervisors had MLL (92% versus 80%; P = 0.02). The longer the GP had been a supervisor the more likely they were to have MLL (P = 0.04). Supervisor reports from MLL practices showed that 81% had used some form of shared learning in the previous year. 24% of GPRs, 12% of PGPPPs and 25% of medical students from MLL practices reported receiving one-to-one teaching exclusively. Approximately 25% of GPRs and 20% of PGPPPs and medical students were getting ≥50% of their learning as shared learning (Table 2). Supervisors’ qualitative comments suggested some RTPs mandate that all paid teaching be one-to-one. The most common forms of shared learning were educational sessions specifically targeting learners, and practice meetings. Most of the learners preferred a mixture of shared learning and one-to-one learning (Figure 1). |

|

| Figure 1. Learners’ preferences for the style of teaching SL, shared learning; GPRs, general practitioner registrars, PGPPPs, prevocational general practice placement program; MSs, medical students |

|

Table 2. Percentage of scheduled teaching time delivered via shared learning sessions in multi-level learner practices.

|

|

Time spent on shared learning

|

GPSs

(n = 226)

|

GPRs

(n = 184)

|

PGPPPs

(n = 226)

|

MSs

(n = 168)

|

|---|

|

None

|

19%

|

24%

|

13%

|

25%

|

|

1–25%

|

39%

|

27%

|

47%

|

42%

|

|

26–<50%

|

19%

|

21%

|

19%

|

14%

|

|

50–<75%

|

18%

|

16%

|

9%

|

9%

|

|

75–100%

|

5%

|

11%

|

12%

|

10%

|

|

GPSs, GP supervisors; GPRs, GP registrars; PGPPPs, junior doctors in general practice; MSs, medical students

|

|---|

Support for participating in shared learning was strong across all groups. Supervisors agreed it was a more cost-effective and time-efficient model, compared with one-to-one teaching. All groups believed it created capacity to take on more learners and build collegial relationships (Table 3), and that leadership and practice management support were important for facilitating shared learning. Supervisors felt having clear evidence of time efficiencies would be helpful, and learners valued collegial relationships (Table 4). Learners who had experienced shared learning were significantly more likely to agree or strongly agree that they were (or would be) happy to participate in shared learning (96.2% vs 79.8%; P <0.001)

Table 3. Stakeholders’ beliefs about shared learning sessions on the shared learning scale

|

|

Statement

|

GPSs

(n = 177)

ⅹ (SD)

|

GPRs

(n = 135)

ⅹ (SD)

|

PGPPPs

(n = 187)

ⅹ (SD)

|

MSs

(n = 121)

ⅹ (SD)

|

|---|

|

Learners are happy to participate in SL sessions

|

4.2 (0.6)

|

4.3 (0.7)

|

4.3 (0.5)

|

4.4 (0.7)

|

|

SL is more time efficient for the supervisor than one-to-one teaching

|

4.4 (0.7)

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

SL is more cost-effective than one-to-one teaching

|

4.3 (0.8)

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

SL sessions are an effective way to teach learners in general practice

|

4.3 (0.6)

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

4.1 (0.6)

|

4.2 (0.8)

|

|

SL creates capacity to take on more learners

|

4.3 (0.7)

|

4.1 (0.7)

|

4.2 (0.6)

|

4.2 (0.9)

|

|

SL sessions build collegial relationships in the practice

|

4.3 (0.7)

|

4.2 (0.6)

|

4.1 (0.6)

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

|

Shared learning sessions provide me with an opportunity to benchmark my level of knowledge

|

–

|

4.0 (0.6)

|

4.0 (0.6)

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

|

SL sessions provide learners with a broader learning experience than one-to-one

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

3.6 (0.9)

|

3.7 (0.8)

|

3.6 (1.0)

|

|

SL sessions are more stressful to teach than one-to-one sessions

|

3.5 (1.0)

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

Compared to one-to-one teaching, SL sessions cause less disruption to clinical contact time

|

3.8 (1.0)

|

3.1 (0.97)

|

3.2 (1.0)

|

3.1 (1.0)

|

|

Shared learning sessions demonstrated to me that it is OK to make mistakes

|

–

|

3.7 (0.84)

|

3.7 (0.8)

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

|

ⅹ, mean score; SD, standard deviation; SL, shared learning; on this scale 1 = strongly disagree; 2= disagree; 3 = not sure; 4 = agree;

5 = strongly agree therefore items with a mean score of 4 or more (indicated in bold) represented agreement with the item

|

|---|

Table 4. Facilitators of shared learning in general practice on a 4-point Likert scale*

|

|

Statement

|

GPs (MLL)

(n = 219*)

ⅹ (SD)

|

GPs (SLL)

(n = 29)

ⅹ (SD)

|

GPRs

(n = 203)

ⅹ (SD)

|

PGPPPs

(n = 263)

ⅹ (SD)

|

MSs

(n = 268)

ⅹ (SD)

|

|---|

|

Leadership in the practice

|

3.3 (0.9)

|

3.1 (0.9)

|

3.1 (0.8)

|

3.0 (0.8)

|

3.0 (0.8)

|

|

Practice management support

|

3.3 (0.8)

|

3.1 (1.0)

|

3.1 (0.7)

|

3.0 (0.8)

|

2.8 (0.9)

|

|

More than one supervisor in the practice involved in teaching

|

3.1 (0.9)

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

2.9 (0.8)

|

2.8 (0.9)

|

|

Access to clinical resources, eg guidelines, online tools

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

3.2 (0.8)

|

3.3 (0.7)

|

3.2 (0.8)

|

3.2 (0.7)

|

|

Teacher training for the person running the shared learning session

|

2.9 (0.9)

|

3.0 (0.7)

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

2.9 (0.8)

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

|

A collegial relationship between the supervisor and the learners

|

–

|

–

|

3.3 (0.7)

|

3.2 (0.7)

|

3.3 (0.7)

|

|

Learners who are confident to interact in groups

|

–

|

–

|

3.0 (0.7)

|

2.9 (0.7)

|

3.0 (0.7)

|

|

Clear evidence of time efficiencies related to shared learning

|

3.0 (0.8)

|

3.0 (0.9)

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

x, mean score; SD, standard deviation; MLL, multiple levels of learner; SLL, single level of learners

*Some missing data

Item ranking options were 1 = unimportant; 2 = mildly important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = very important; items with a mean score of 3 or more (indicated in bold) meant the item was considered moderately important

|

|---|

Only one barrier reached moderate importance: lack of space in single-level learner (SLL) practices (Table 5). Qualitative comments from SLL supervisors suggested that lack of space was the single most important barrier to taking on additional learners (44% of comments). Overall, SLL supervisors ranked barriers as significantly more important than did MLL supervisors (mean 2.5 (± 0.6) versus 2.1 (± 0.6, s.d.; P <0.01). The lower the level of the learner in the training hierarchy, the higher they ranked barriers in importance (medical students: 2.56 ± 0.53; PGPPPs: 2.43 ± 0.52; GPRs: 2.39 ± 0.57; P = 0.001), although post hoc tests determined that the significant difference was between medical students scores and those of PGPPPs and GPRs. The mean score on the barriers scale was 2.43 (± 0.50) for those learners who had not been exposed to shared learning and 2.37 (± 0.54) for those with experience of shared learning. The difference in means was not statistically significant.

Table 5. Barriers to shared learning in general practice on a 4-point Likert scale

|

|

Statement

|

GPs (MLL)

(n = 217*)

ⅹ (SD)

|

GPs (SLL)

(n = 29*)

ⅹ (SD)

|

GPRs

(n = 203)

ⅹ (SD)

|

PGPPPs

(n = 263)

ⅹ (SD)

|

MSs

(n = 267)

ⅹ (SD)

|

|---|

|

Disparate learning needs of different levels of learner

|

2.5 (0.9)

|

2.5 (0.8)

|

2.8 (1.0)

|

2.8 (0.8)

|

2.8 (0.9)

|

|

Scheduling shared learning sessions

|

2.5 (1.0)

|

2.8 (1.2)

|

2.8 (0.9)

|

2.8 (0.8)

|

2.7 (0.9)

|

|

Lack of space

|

2.4 (1.1)

|

3.2 (1.1)

|

2.2 (0.9)

|

2.3 (0.8)

|

2.6 (0.9)

|

|

Learners' short placements

|

2.3 (1.0)

|

2.1 (0.9)

|

2.2 (0.9)

|

2.5 (0.9)

|

2.7 (0.9)

|

|

The time required to prepare for a shared learning session

|

2.3 (1.0)

|

2.8 (1.1)

|

2.4 (0.9)

|

2.5 (0.8)

|

2.5 (0.8)

|

|

Lack of specific training in teaching groups of learners at different levels

|

2.1 (0.9)

|

2.3 (0.9)

|

2.6 (0.9)

|

2.6 (0.9)

|

2.8 (0.8)

|

|

Confidence to facilitate a shared learning session

|

1.9 (1.0)

|

2.4 (1.1)

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

The stress involved in facilitating/ participating in a shared learning session

|

1.7 (0.8)

|

2.3 (1.0)

|

1.9 (0.9)

|

2.0 (0.9)

|

2.1 (0.9)

|

|

Fear of learners who disrupt the group dynamic

|

1.5 (0.7)

|

1.8 (0.9)

|

2.6 (1.0)

|

2.6 (1.0)

|

2.9 (0.9)

|

|

Fear of being judged

|

–

|

–

|

2.0 (1.0)

|

2.1 (0.9)

|

2.2 (1.0)

|

|

x, mean score; SD, standard deviation; MLL, multiple level learners; SLL, single level learners; MSs, medical students

*Some missing data

Item ranking options were 1 = unimportant; 2 = mildly important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = very important; items with a mean score of 3 or more (indicated in bold) meant the item was considered moderately important

|

|---|

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge that has captured a substantial quantitative dataset providing evidence about shared learning that may be generalised across the Australian GP training environment. New insights from these data include the higher uptake of MLL in rural/remote areas, the high level of support for a mixture of shared learning and one-to-one teaching amongst learners, the degree to which lack of space is seen as a barrier by SLL supervisors, and the degree to which supervisors see shared learning as an effective teaching model that creates training capacity. These results also provide an estimate of the uptake of shared learning in Australian general practices.

The comparatively low uptake of shared learning models in the face of positive attitudes towards it suggests that there is capacity to facilitate increased uptake, which would increase the likelihood of supervisors taking on multiple learners and therefore training places. Providing supervisor training in small group facilitation and targeted practice management support may further increase adoption of shared learning by improving supervisors’ confidence to manage group teaching. RTPs should recognise that shared learning models are seen by learners and supervisors as effective and beneficial teaching models, and as such should be encouraged, as long as there is also some mandated one-to-one teaching time to meet learners’ specific needs. The need for some mandatory one-to-one teaching has been suggested in previous qualitative studies.8,9 Lack of space has been previously suggested as a barrier to having MLL practices,9,12 but our results indicate that this is the most important barrier for SLL GPs, suggesting infrastructure support should be investigated as one way to grow the number of MLL practices.

Supervisors and learners who had experienced MLL practices often rated barriers to shared learning as less important than those who did not, suggesting that providing an opportunity for all groups to interact can act as a facilitator. This trend can also be seen in previous research in the area of registrars teaching.20,21

The benefits of shared learning include a collegial learning experience for learners and supervisors. Supervisors also suggested that shared learning models are more cost-effective and time-efficient than one-to-one teaching. RTPs and universities should collaborate to provide information to practices and supervisors on the mix of learners and teaching models that can make supervision most cost-effective and time-efficient as a means of increasing capacity. Laurence et al22 have demonstrated cost efficiencies with models of teaching that include MLLs in the same practice.

Although this study involved a large national sample, those with a greater interest in shared learning may have been more likely to respond, and the response rate was not high. However, in most instances participants’ demographics were similar to national demographics where such statistics were available. For example, the proportion of vocational training by remoteness area was identical to the national sample.18 It is also possible that some participants inadvertently completed the survey twice or that responses were influenced by socially desirable responding.23 The strength of this study is that it sought the views of a large and diverse sample of stakeholders who may be influenced by shared learning across urban, rural and remote locations in Australia.

Conclusion

Supervisors and learners in general practice have positive attitudes towards shared learning, seeing it as effective, cost-effective and time-efficient, collegial and able to build training capacity. Most of the learners preferred a mixture of shared learning and one-to-one teaching. Increasing the uptake of such models through support to supervisors can help address general practice training capacity. Finding strategies to get supervisors and different levels of learners to interact in groups will break down barriers to implementation of shared learning models.

Implications for general practice

- Shared learning models offer a means of addressing general practice training capacity constraints while providing effective teaching and building collegial relationships in the practice.

- Infrastructure support is critical to helping supervisors in single level learner practices to move to supervision of multiple levels of learner.

- Learners prefer a mixture of one-to-one and shared learning rather than one type of teaching alone.

- Regional training providers should support the implementation of shared learning models in their regions.

Competing interests: Thea van de Mortel, Peter Silberberg and Christine Ahern have had grants paid to their institutions by Health Workforce Australia.

Sabrina Pit has received a consulting/honorarium fee from North Coast GP Training.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.