General practitioner (GP) after-hours helpline services have been introduced across various countries worldwide in an attempt to assist in managing demand for primary healthcare services and facilitate equity of access.1,2 To evaluate the effectiveness of GP after-hours helplines, most previous studies have focused on determining the impact of these helplines on emergency department (ED) over-crowding.3,4 Few studies have explored the actual usage of these services, the types of care advice provided by GPs, or if the advice provided differs from what the caller intended to do prior to calling the after-hours helpline.1,5 In July 2011, a national ‘after hours GP helpline’ (AGPH) service was introduced by Healthdirect Australia.6 Registered nurses triage calls and, if appropriate, transfer callers to a telephone-based GP for additional advice. As with after-hours physician services in the US,7 medication-related queries are the most frequent type of calls received by the AGPH.8

This study was conducted to examine medication-related queries received by the AGPH during a one-year period (2014). In addition to caller demographics and problem details, the helpline also recorded callers’ original intentions/intended actions prior to contacting the helpline. The triage nurse recorded these calls before forwarding them to the AGPH. Our aim was to describe medication-related queries received by the AGPH and examine if the care advice provided by after-hours GPs was consistent with the type of care pathway callers had intended to follow prior to calling the helpline. We also conducted an audit of the free text entered by GPs in one month (November 2014) to identify the reasons for medication queries received by GPs.

Methods

The AGPH service operates from 6.00 pm to 8.00 am Monday to Friday, from 12.00 pm Saturday to 8.00 am Monday, and 24 hours a day on public holidays. A detailed descriptive analysis of medication-related queries received by the AGPH in 2014 was performed to examine:

- the volume of medication-related calls over time

- the type of care advice provided (Appendix A, available online only)

- callers’ intended actions prior to calling the helpline (to allow the care advice given by GPs and the callers’ intended actions to be compared).

GPs documented the medication problem as described by the caller in a free-text field in the computerised decision support system. The descriptions entered were used to assign the callers’ queries to one of 10 possible reasons for the call (defined in Appendix B, available online only). These categories were developed on the basis of an initial review of the data by research team members. Based on this classification, data were then analysed to identify the distribution of queries by the type of care advice given by the GPs. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from Macquarie University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 5201401161).

Results

Distribution of medication-related calls to the helpline

In 2014, the helpline received 39,344 medication-related calls. Of these calls, 65.43% (n = 25,744) were managed by the triage nurse and the remaining 34.57% (n = 13,600) were forwarded to the AGPH. These 13,600 medication-related calls represented 6.51% of the total calls (n = 208,837) received by the AGPH in 2014.

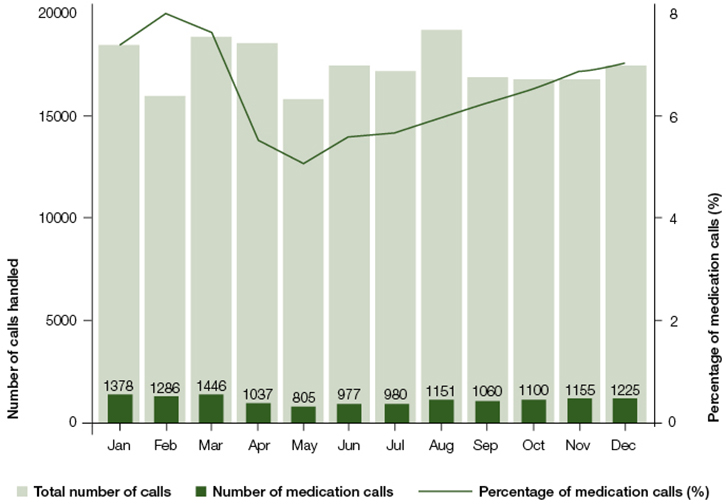

The percentage of medication-related calls varied each month and January–March had the highest proportion of these calls (Figure 1). Of all medication-related calls, 16.96% related to paediatric medications and 83.04% related to adult medications. August and September had the highest percentage of paediatric medication-related calls.

Figure 1. Distributions of all calls to AGPH and medication related calls over time in 2014

Callers’ intentions and advice given by after-hours GPs

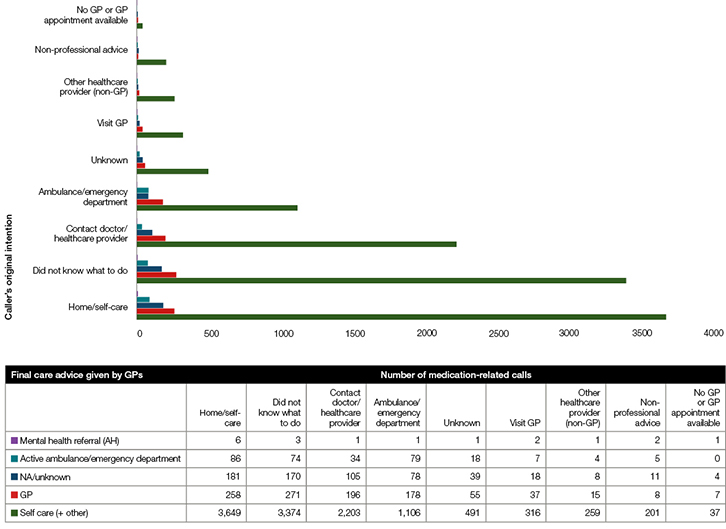

Nearly one-third of the 13,600 callers with medication-related queries (30.70%; n = 4175) planned to administer self-care prior to calling the AGPH; 28.60% (n = 3890) reported that they did not know what to do; and 10.60% (n = 1442) of callers intended to visit an ED or call triple zero for an ambulance. For the majority of calls (85.56%), GPs advised callers to either self-care only, or self-care overnight and see their GP or another healthcare professional during the next working day. The GPs only advised 2.26% (n = 307) of callers to contact or visit emergency services.

Figure 2 shows a comparison of patients’ intended actions and the final care advice provided by the GPs on the helpline. In 1442 cases, the callers originally intended to call for an ambulance or attend an ED. More than three-quarters (76.70%) of these callers were advised by the GPs to administer self-care only or self-care overnight and see their GP or healthcare professional during the next working day (grouped as Home/self-care in Figure 2). Only 5.48% (n = 79) of these callers were transferred to triple zero or advised to go to an ED. Of the 4180 calls where the callers’ original intention was to administer self-care, 86 cases (2.06%) were transferred to triple zero or advised to visit an ED. An additional 74 callers, where callers did not know what to do prior to contacting the helpline, were transferred to triple zero or were advised by the GPs to visit an ED.

Figure 2. Number of medication-related calls by caller’s original intention and final care advice by GPs

Reasons for calling the helpline

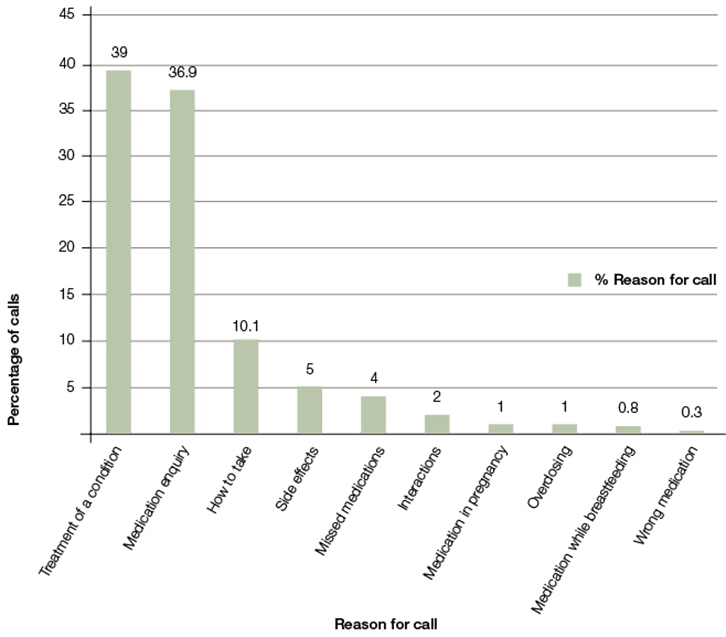

To examine the common reasons and timings of medication-related queries received by the AGPH, data from November 2014 (n = 1155) were further analysed. For medication-related calls referred to the AGPH in November 2014, the greatest proportion (46.70%) occurred during the hours of 10.00 pm – 8.00 am. Twenty-four cases were excluded from our analysis as information on the reason for the call was missing. The associated data field in these cases was empty, which may be attributed to technical issues such as call drop-off. Of the remaining 1131 medication-related calls, 36.90% of the queries contained insufficient information to allow the reason for the call to be classified (Figure 3). We found that 39.03% of the queries were from callers enquiring about treatment of a specific condition. A further 10.09% of queries were from patients asking how to take medications, which included queries about route of administration and dose of a medication.

Figure 3. Distribution by reason for medication-related calls in November 2014

In November 2014, 117 callers originally intended to contact or visit emergency services. However, only 14 (11.97%) of these callers were advised by the GP to contact or visit emergency services; most of these callers (n = 11) had only called to seek advice on treatment of a condition (Appendix C, available online only). Of the 366 callers who originally intended to administer self-care, 13 (3.55%) were advised to visit an ED or were transferred to triple zero; most of these (n = 10) had also only called to get advice on treatment of a condition.

Discussion

This study examined the medication-related queries received by the AGPH to compare the care advice given by GPs to the actions the caller had intended to take prior to contacting the helpline. We found that 2.26% of callers were directed to visit an ED or were transferred to triple zero. This was despite a larger number of people (10.60%) calling the helpline with an intention to visit the ED. Thus, the availability of an after-hours service potentially prevented 1363 people from unnecessarily attending an ED. At the same time, the helpline directed 228 callers to emergency services who had underestimated the seriousness of their condition and may not have had timely treatment. Although a limitation of this study was that we did not follow up and assess callers’ compliance with the GPs’ advice,8 a previous study suggests that the majority of callers follow the advice provided by GPs.4 That study linked records from the AGPH for one year (2000) with the records of an ED. It found that 79% of callers (n = 842) complied with the advice given by the GPs.4

Despite the high levels of reported compliance with GP advice, it has been claimed that after-hours clinical helplines have a limited impact on ED overcrowding.3 This may be because the helpline is not being used to its full potential. Limited population-level awareness and uptake of the helpline can be potential contributory factors in restricting its impact. A recent Australian study that aimed to determine patients’ points of contact prior to presenting to the ED for treatment identified a large proportion of patients (n = 200, 60.2%) were self-referred presentations. Only three out of 332 (0.90%) patients had contacted the Healthdirect helpline or the AGPH prior to visiting the ED.9 This may indicate limited awareness among consumers regarding the availability of a national AGPH.

Limited awareness of an available helpline has also been reported in the UK for the National Health Service (NHS) 111 telephone service, set up to improve and simplify access to non-emergency NHS healthcare in England.10 In a survey of 8010 members of the general population, 59% of respondents reported that they had heard about NHS 111 but only 9% reported ever using the service.10 A similar population-based survey of 2477 people in the general population in Australia reported that 31% of respondents were aware of Healthdirect Australia’s services.11 Of these, 80% (n = 623) had never used it, 12% (n = 92) had used it once and 7% (n = 55) has used it two to three times. Identification and execution of potential strategies to increase awareness of the helpline may improve its use and impact.

Our investigation of free-text problem descriptions for November 2014, although limited because of poor data quality, indicated that the most common reason for a medication-related call was to enquire about the treatment of a condition(s). In most cases, medication names were not included in the description. The provision of dropdown lists with medication classes (eg antihistamines) for providers would allow the helpline to better understand consumer needs and examine the use of different types of medications in the community.

The AGPH provides consumers with a quick and easy alternative to visiting a GP or pharmacist for gaining medication-related information, especially after-hours when availability of other services is limited. Overall, the AGPH provides medication-related advice to more than 13,000 consumers annually, preventing unnecessary visits to the ED and directing consumers to the ED when they may need more urgent treatment than they otherwise realise. The full potential of the service is not currently being realised because of its limited use.

Authors

Amina Tariq PhD, MSc (BITS), BEng (Software), Lecturer (e-health), Visiting Research Fellow, School of Public Health and Social Work, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Qld; Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW. a.tariq@qut.edu.au, amina.tariq@mq.edu.au

Ling Li PhD, MBiostats, MComIT, MComBus, BEcon, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW

Mary Byrne MHL, BA (Hons), BTheol, BHS (Nursing), Senior Policy Analyst, Clinical Governance, healthdirect Australia, Sydney, NSW

Maureen Robinson DipPhys, MHA, FAAQHC, GAICD, General Manager, Clinical Governance, Healthdirect Australia, Sydney, NSW

Johanna Westbrook PhD, MHA, GradDipAppEpid, BAppSc, Director and Professor, Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW

Melissa T Baysari PhD, BPsych, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW. St Vincent’s Clinical School, UNSW Medicine, UNSW, Sydney, NSW

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The study was commissioned by healthdirect Australia and was conducted as a part of a project to review their telephony and digital medication services.

References

Appendix A. Types of care advice given by the GPs

|

Type of care advice

|

Description

|

|

Active 000 or ED

|

GP either transfers the caller directly to a ‘000’ ambulance service or recommends the caller visits an emergency department immediately

|

|

See GP or other healthcare professional

|

GP recommends the caller sees a GP or other appropriate health provider immediately or within the next 24–48 hours

|

|

Self-care/other

|

GP recommends care that can be administered by the caller themselves

|

|

Mental health referral [AH]

|

GP refers the caller to a mental health helpline service

|

|

Unknown/NA

|

The care advice given by the GP was not recorded (reasons unknown)

|

Appendix B. Reasons for medication-related calls to the ‘after hours GP helpline’ in November 2014

|

Type of Reason

|

Description

|

|

Medication enquiry - not classified

|

Limited or insufficient detail available. Listed as ‘Medication enquiry’, ‘Medication question’ or ‘NA’

|

|

Side effects

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about side effects of a particular medication

|

|

Interactions

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about possible interactions between one medication and another

|

|

How to take

|

Description indicates that caller wants to know how to take a particular medication (dose, time, etc)

|

|

Overdosing

|

Description indicates that patient has taken an overdose of a medication

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

Description indicates that caller is seeking medication-related advice related to a condition(s) or symptoms (eg fever) of a condition

|

|

Medication in pregnancy

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about use of medications during pregnancy

|

|

Medication while breast feeding

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about use of medications while breast feeding

|

|

Missed medications

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about missed medications or a missed dose of a medication

|

|

Wrong medication

|

Description indicates that caller is enquiring about taking a wrong medication

|

Appendix C. Distribution of calls in November 2014 by callers’ intention, care advice by GP and reason for call

|

Caller’s original intention

|

Care advice given by the GP

|

Reason for call

|

Number of calls

|

|

Ambulance/ED

|

Active 000/ED immediately

|

How to take

|

2

|

|

|

|

Side effects

|

1

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

11

|

|

|

See GP or other healthcare professional

|

Interactions

|

1

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

5

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

12

|

|

|

|

How to take

|

1

|

|

|

|

Overdosing

|

2

|

|

|

|

Side effects

|

1

|

|

|

Self-care advice + other

|

How to take

|

7

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

24

|

|

|

|

Missed medications

|

2

|

|

|

|

Side effects

|

3

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

34

|

|

|

|

Wrong medication

|

1

|

|

|

|

Medication in pregnancy

|

2

|

|

|

|

Overdosing

|

1

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

9

|

|

|

Unknown/not applicable

|

Medication enquiry

|

7

|

|

Ambulance/ED total

|

|

|

117

|

|

Home/self-care

|

Active 000/ED

|

How to take

|

1

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

10

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

2

|

|

|

GP

|

Interactions

|

2

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

2

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

10

|

|

|

|

How to take

|

1

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

4

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

3

|

|

|

Self-care advice + other

|

How to take

|

37

|

|

|

|

Interactions

|

7

|

|

|

|

Medication enquiry

|

114

|

|

|

|

Medication in pregnancy

|

2

|

|

|

|

Medication while breast feeding

|

3

|

|

|

|

Missed medications

|

4

|

|

|

|

Overdosing

|

2

|

|

|

|

Side effects

|

12

|

|

|

|

Treatment of a condition

|

131

|

|

|

Unknown/not applicable

|

Medication enquiry

|

13

|

|

Home/self-care Total

|

|

|

366

|