Home blood pressure (BP) monitoring, the self-measurement of BP in the home, away from a medical environment, provides a greater number of BP readings that are more reliable for assessment of true underlying BP than clinic BP measurement. While 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring is the gold standard method to assess BP control, it is not always practical to use this in general practice. Home BP monitoring is already in widespread use,1 but many factors can affect the reliability of BP readings. A standardised approach to measuring home BP is recommended to help minimise error.

The purpose of this article is to provide a practical summary guide for Australian healthcare professionals and their patients on how to measure home BP using a standardised, evidence-based protocol. Pragmatic resources for ease of clinical implementation are also provided. It is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed rationale for using home BP monitoring in general practice. This topic is extensively addressed in several international guidelines,2–4 including an Australian consensus statement5 in which evidence is provided to show that home BP monitoring offers advantages beyond clinic BP measurement in terms of:

- better evaluation of BP control

- better prognostic indication

- greater engagement of patients

- improved compliance with drug therapy.

Standardised measurement of home BP

What type of BP device to use?

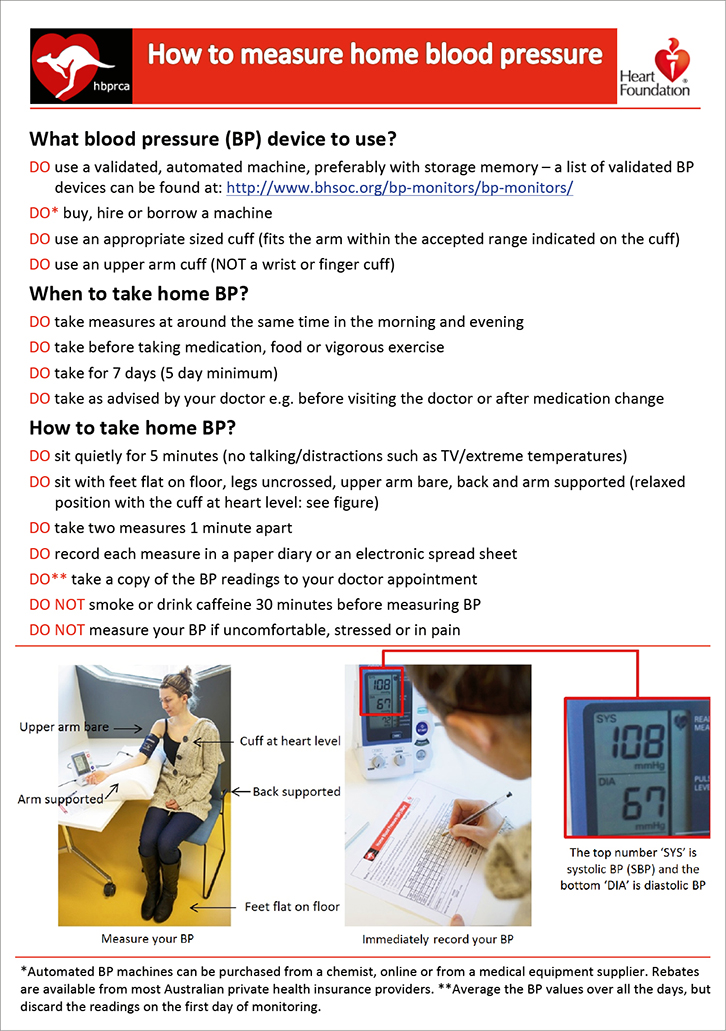

The BP device should be validated, automated, preferably with memory storage, and used with a correctly sized upper arm cuff. Device validity should be tested in the patient population intended for its use.4 A list of validated devices can be found at www.bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Standardised method on how to measure home blood pressure |

Inaccurate recording of home BP using patient diaries6–8 is a problem that can be circumvented by using BP devices with memory storage or telemonitoring, if feasible. An appropriately sized cuff that fits the arm within the appropriate range indicated on the cuff must be used. A cuff that is too small will overestimate BP and a cuff that is too large will underestimate BP.9 Wrist and finger cuff monitors are less likely to have passed validation testing and should be avoided.4 A validated wrist device may be a reasonable option in patients with a large arm circumference that is beyond the maximum cuff range. Intermittent servicing (eg every three years) to check device condition and accuracy is generally recommended, and devices should be serviced or replaced if the accuracy is questionable. This process can be carried out through contact with the local distributor of the device.

When should home BP be taken?

Ask the patient (and provide written material) to measure their BP at around the same time in the morning and the evening over a seven-day period. Monitoring may be for initial assessment of BP, but also to assess the effectiveness of treatment, and typically would include the following options:

- the seven-day period before a clinic visit

- approximately four weeks after initiating a change in medication10

- at regular, long-term intervals (eg six months) in keeping with appropriate clinical follow-up according to cardiovascular risk.11,12

The repeat measurement of home BP over seven days helps to narrow the variability of BP around the true mean BP value,13 and generally provides the highest prognostic and diagnostic capacity in comparison with shorter monitoring periods.14,15 However, a minimum of five days may also provide a good indication of BP control.16

Home BP should be recorded in the morning and evening before medication (if treated).17-–20 Home BP may also be recorded at other times, such as in the late morning when BP may be at the lowest for the day (particularly if medications are taken in the morning, or if symptoms suggest), and their measurement may help protect against over-medication. Late morning readings may also provide guidance on optimising the timing of medications (eg morning versus night-time), assisted by 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring where necessary. Home BP should be taken after voiding and before food or vigorous exercise, as all these factors can affect BP. Caffeine and cigarettes can each acutely raise BP21,22 and BP measurement should be undertaken before, or at least 30 minutes after, these stimulants.

How should home BP be taken?

Two measurements should be taken in a quiet room after five minutes of seated rest, with readings taken one minute apart. BP should be recorded immediately in a diary (Figure 2) if the device has no memory function or is not telemonitored. The overall home BP value is derived by averaging the BP values over the seven-day monitoring period after discarding the first day of readings (ie average of 24 home BP readings). Electronic recording of BP values directly into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with automatic averaging of BP values is available online.

An average home BP measurement of ≥135/85 mmHg is an appropriate threshold for the diagnosis of hypertension.5

The patient should be in the seated position with feet flat on the floor, legs uncrossed, upper arm bare, back supported and arm supported in a relaxed position with the cuff at heart level (Figure 1). If the cuff is significantly above or below heart level, the BP measurements may be decreased or increased respectively.23 If the cuff is applied so that its midpoint is about the midpoint of the upper arm, this will approximate the level of the heart. Patients should not be distracted (eg talking, watching television). Similarly, if the patient is affected by extremes of temperature, or is uncomfortable, stressed or in pain, BP should not be taken.

After five minutes of rest, the patient should take two consecutive measurements one minute apart and, after each measurement, record the systolic and diastolic BP. If patients are not compliant with a rest period before recording BP, this could lead to higher home BP values.24 They should be asked to note in the diary anything unusual that may affect readings. Standing BP measurements may be requested when orthostatic hypotension is suspected; BP measurements at one and three minutes after standing are recommended.5

Key points

- Home BP monitoring provides a more reliable assessment of true underlying BP than clinic BP measurement.

- Many factors can affect reliability of home BP monitoring and a standardised approach is advised in order to minimise error.

- Standardised measurement includes:

- using a validated BP device with correct cuff size

- duplicate measurements in the morning and evening over seven days (five days minimum)

- measurements being taken in a quiet room after five minutes of seated rest (record in a diary).

- Average home BP ≥135/85 mmHg is the threshold for diagnosis of hypertension.

- Practical materials (Figures 1, 2 and the electronic home BP diary) are accessible on the AFP website. Links to these materials are provided in the figure legends and the ‘Resources’ section.

Authors

James Sharman BHMS (Hons), PhD, Associate Professor and Senior Research Fellow, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS. james.sharman@utas.edu.au

Faline Howes MBBS, General Practitioner, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS

Geoffrey Head BSc, PhD, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC

Barry McGrath MBBS, PhD, Professor of Vascular Medicine & Medicine, Monash University, Clayton, VIC

Michael Stowasser MBBS, PhD, Professor of Medicine, Director of the Hypertension Units, Endocrine Hypertension Research Centre, University of Queensland School of Medicine, Greenslopes and Princess Alexandra Hospitals, Brisbane, QLD

Markus Schlaich MBBS, PhD, Renal Physician and Hypertension Specialist, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC; School of Medicine and Pharmacology, Royal Perth Hospital Unit, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

Paul Glasziou MBBS, PhD, General Practitioner and Professor of Evidence-Based Medicine, Centre for Research in Evidence Based Practice, Bond University, QLD

Mark R Nelson MBBS, PhD, Chair, Discipline of General Practice, and Senior Professorial Fellow, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been endorsed by the High Blood Pressure Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Foundation of Australia. The writing group is very grateful to Jinty Wilson from the National Heart Foundation of Australia for her significant input to the content of this paper.

Resources