In Australia today, most people live longer with more comorbidities and die an expected death from chronic, progressive conditions such as dementia, cancer and frailty syndromes.1 General practitioners (GPs) have an essential role in caring for these patients and proactively planning their end-of-life care. A framework using a palliative care approach can support GPs to develop proactive, patient-centred management plans that avoid the need for decision making in emotionally charged situations.2,3

Most older people would prefer and benefit from care focused on their unique goals and quality of life, rather than that aimed at extending biological life.4 This approach can prevent unnecessary and burdensome interventions, as well as unwanted hospital admissions, and support Australians who wish to die at home (reportedly 70%).5,6

Modern medicine and palliative care

GPs report they infrequently practice palliative care while, in reality, they care for many older people whose health conditions are likely to lead to death in the near future.7 Given this, it may be useful for GPs to reconsider how they define and practice palliative care.

Modern palliative care is considered pertinent to all who will die an expected death.8 For this patient cohort, early identification of needs allows the best quality of remaining life. Palliative care is influenced by increasing medical advances in disease-modifying treatments. Indeed, in contemporary medicine, the distinction between curative and palliative is blurred, creating challenges for clinicians and patients alike. There is no absolute demarcation point between curative and palliative intent. That point differs for each individual, and treatment decisions are influenced by patient factors such as medical condition, culture, related health experiences, religion, spirituality, personality and socioeconomic demographics. Research shows that, particularly for patients with a non-malignant illness, GPs are less confident to initiate palliative care, provide timely referrals to specialist services and discuss end-of-life issues.9 This can result in lost opportunities for patients to understand that death is inevitable, to plan for their deaths and to have those plans realised.

The framework of palliative care

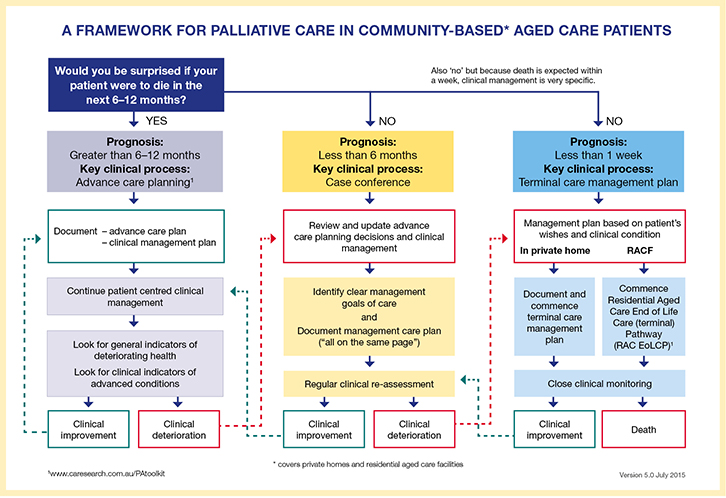

The framework of palliative care (the framework; Figure 1) is a tool based on three prognostic trajectories. It was developed to support GPs to proactively manage their patients’ care as it transitions from curative to palliative, and to facilitate a high-quality end of life according to patients’ preferences. It was founded on work undertaken in the UK10 and Australia.11

|

| Figure 1. A framework for palliative care of community-based aged care patients11 |

The framework commences by asking the question: ‘Would you be surprised if your patient were to die in the next 6–12 months?’ This is ideally embedded into routine practice in a systematic way; for example, at the 75+ health check, at a given time before or after entry into a residential aged care facility (RACF) or after an older person is hospitalised.

This question can be answered using clinical knowledge, personal knowledge of the patient, clinical intuition and/or by using clinical prognostication tools.

In the first trajectory (prognosis of >6–12 months), when the answer to the question is ‘yes’, the key clinical process is advance care planning. This is an interactive, ongoing process of communication between a competent person/substitute decision-maker and all carers, focusing on the person’s preferences for future care.

In the second trajectory (prognosis of <6–12 months), when the answer to the question is ‘no’, the key clinical process is case conferencing. This aims to identify clear goals of care so that carers are ‘all on the same page’. Case conference outcomes should be documented, translated into a management plan and shared with those involved in the person’s care.

In the third trajectory, a diagnosis of dying has been made with a prognosis of usually shorter than a week. The key clinical process is the development of a terminal care management plan to support the person to die at home or in an RACF.

Conclusion

The framework of palliative care provides the opportunity to improve clinicians’ mindfulness regarding proactive management of clinical needs that typically emerge in the last year of life. It supports communication between the GP and the patient and their carers/substitute decision-makers, thereby enabling informed management plans to be developed in accordance with the patient’s personal choices. Routine implementation of the framework may help to ensure that patients receive the right care, and at the right time and place.

Resources

The Decision Assist website (www.decisionassist.org.au) contains information about educational opportunities and resources to support GPs to care for older Australians living in the community with chronic life-limiting illnesses.

Authors

Liz Reymond MBBS (Hons), FRACGP, FAChPM, PhD, Professor, Deputy Director, Metro South Palliative Care Service, Metro South Health, Queensland Government, Brisbane, QLD. elizabeth.reymond@health.qld.gov.au

Karen Cooper BSc (Hons), PhD, Project Manager, the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine, Canberra, ACT

Deborah Parker RN, BA, MSocSci, PhD, Director, Centre for Applied Nursing Research, Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Research, University of Western Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Michael Chapman MBBS, FRACP, FAChPM, Palliative Medicine Consultant, Calvary Bruce, Canberra, ACT

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

Decision Assist is funded by the Department of Health.