Over the past two decades, interest in working in developing countries has increased among Australian health professionals. This is illustrated by the growth in global health-related postgraduate courses – these are now offered at 16 tertiary institutions in every state and territory of Australia, and at two universities in New Zealand.

The Global Health Gateway website describes itself as ‘Australia and New Zealand’s hub for global health careers’, and provides advice on study and employment options.1 The annual Global Ideas Forum in Melbourne attracts more than 400 participants, described variously as ‘health adventurers, leaders, campaigners, community organisers and entrepreneurs’.2 The Australian Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Doctors in Training conference in 2015 had a major focus on global health.

Interest in global health often starts in medical school. AMSA Global Health is now the Australian Medical Students’ Association’s largest committee and represents 20 global health groups at every Australian medical school.3 The AMSA’s Global academy provides online training in five global health modules.

What is global health?

Koplan et al defined global health as:4

… an area for study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasises transnational health issues, determinants and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes inter-disciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.

Health in low-income and middle-income countries

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have guided health development efforts for the past 15 years.5 Compared with 1990, the health of the world’s people has significantly improved. For example, the United Nations (UN) recently reported that global life expectancy had reached 70 years of age for the first time.6 However, major differences remain between geographic regions. In general, health indicators in Sub-Saharan Africa are significantly worse than other regions. In the Asia-Pacific region, there is considerable variation; for example, life expectancy varies between 65 years of age in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and 80 years of age in Vietnam.7 Table 1 shows differences in key health indicators, such as child and maternal mortality, and fertility rates, in 10 Asia-Pacific countries. Very high rates of child malnutrition, in the form of stunting (low height for age), are seen in some South-East Asian and Pacific countries, including Timor-Leste (50%), PNG (44%) and Cambodia (41%).8

Table 1. Child mortality, maternal mortality and fertility rates in selected Asia-Pacific countries

|

| | Under-5 mortality rate

(per 1000 live births in 2012) | Maternal mortality rate

(per 100,000 live births in 2013) | Fertility rate

(live births per woman in 2014) |

|---|

| Sri Lanka |

10 |

29 |

2.3 |

| Thailand |

13 |

26 |

1.4 |

| Bangladesh |

18 |

170 |

2.1 |

| Fiji |

22 |

59 |

2.6 |

| Indonesia |

31 |

190 |

2.3 |

| Cambodia |

40 |

170 |

2.8 |

| Myanmar |

52 |

200 |

1.9 |

| Timor-Leste |

57 |

270 |

5.7 |

| Papua New Guinea |

63 |

230 |

3.7 |

| Laos |

72 |

220 |

2.9 |

| Australia |

4.9 |

6 |

1.9 |

|

Source: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Statistical Yearbook for Asia and the Pacific 2014. Bangkok: ESCAP, 2014.

|

Key approaches to health development

Building blocks

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes six ‘building blocks’ to strengthen health systems:9

- leadership and governance

- healthcare financing

- health workforce

- essential medical products and technologies

- information and research

- service delivery.

This paper will focus on the building block of service delivery, with references to building health workforce capacity.

Primary healthcare

Since the 1978 Alma-Ata conference, primary healthcare has been the recommended approach to deliver comprehensive, appropriate and affordable healthcare in resource-constrained countries. Primary healthcare is characterised by:10

- equitable access to healthcare

- community participation

- health workforce development and needs-based distribution of health personnel

- effective referral systems

- use of appropriate technology

- multi-sectoral approach.

Thirty years after the Alma-Ata conference, The Lancet published a series on primary healthcare, describing a ‘renaissance’ of the approach that would help low-income and middle-income countries achieve the health MDGs.11 A review of the progress showed that the 30 countries with the greatest reductions in child mortality had scaled up selective primary healthcare (eg immunisation, family planning), and 14 had progressed to comprehensive primary healthcare, marked by high coverage of skilled attendance at birth.12

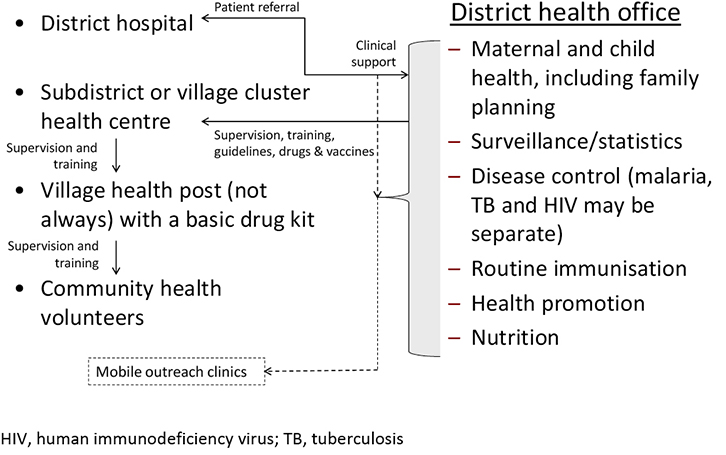

Primary healthcare works best at the district level, supported by evidence-based policies at the national level, and referral facilities at the provincial and national tertiary hospitals. Although there is variation in how health systems are organised, a fairly typical structure of a district health system is illustrated in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1. Typical structure of a district health system |

Healthcare in complex emergencies

Complex emergencies have been defined as ‘situations affecting large civilian populations, which usually involve a combination of factors including war or civil strife, food shortages and population displacement, resulting in significant excess mortality’.13 Recent examples include the millions of Syrians, Afghans and South Sudanese displaced by civil war.

Although a primary healthcare approach is recommended, early relief programs focus on providing shelter, food, water and sanitation, while medical workers address the major causes of death, which are often diarrhoeal diseases (including cholera), malaria, pneumonia, meningitis, hepatitis and malnutrition. There are now excellent technical guidelines and minimum standards that are published in The Sphere Handbook.14 Medical teams are often sent to assist in the aftermath of a natural disaster, such as Cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines, but the immediate priorities are search and rescue, triage and surgical management of wounds.

How can Australian medical professionals contribute?

Non-emergency settings

Probably the most effective contribution is to provide technical support and advice to a primary healthcare program. For example, one of the author’s colleagues advised a Save the Children primary healthcare program for five years in a remote province of Laos. She provided a broad range of technical training either directly or by recruiting appropriate specialists. She also advised the health information system and health promotion program. In this role, epidemiology, health promotion, program management and adult learning skills are highly desirable.

Clinical positions for generalist doctors are unusual. Working at the district level usually involves on-the-job skills training rather than hands-on clinical practice. However, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recruits volunteer doctors and nurses to treat patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in dedicated MSF clinics. One of the author’s Burnet colleagues worked as a volunteer doing diabetes screening in rural clinics in Vanuatu (Figure 2), while another provided home-based care for patients in Sudan who were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive.

|

| Figure 2. Médecins Sans Frontières’ Dr Laura Trivino examining an HIV patient at Masemouse clinic, Lesotho. In 2015, over 200 field positions will have been held by Australians and New Zealanders though Médecins Sans Frontières Australia in countries including Afghanistan, Armenia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Central African Republic, DRC, Ethiopia, Georgia, Greece, Haiti, India, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, SIerra Leone, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Yemen. Copyright: Zethu Mlobeli |

Specialists in various medical fields can take on short-term training roles. For example, one of the author’s Burnet colleagues, a trainee paediatrician, provided on-the-job capacity building for paediatric trainees in Vientiane, Laos. Other specialists who often provide a mix of short-term clinical services and training include eye and maxillofacial surgeons, and anaesthetists.

There are opportunities for generalist doctors to conduct clinical practice overseas in Christian mission hospitals. Countries that have a relatively high number of faith-based hospitals include India, Nepal, Pakistan, PNG and various African countries, including Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. However, a number of problems threaten the sustainability of faith-based hospitals in developing countries; some have been described as under-funded and under-staffed.15

Emergency settings

Australian medical professionals often do their ‘first mission’ in a humanitarian emergency. For doctors, this often involves a mix of clinical work in outpatient and inpatient facilities, and public health (eg disease prevention and surveillance, health worker training and supervision, nutritional rehabilitation). These assignments are usually between six and 12 months.

Following acute natural disasters, Australia’s National Critical Care and Trauma Response Centre, based in Darwin, deploys Australian Medical Assistance Teams (AUSMAT), which are multi-disciplinary health teams.16 Experience in trauma and burn management is highly desirable.

Pathways to the field

The advice provided here is based on the presumption that the readership of this journal comprises family practitioners with generalist medical training. Probably one of the most practical ways for Australian health practitioners to prepare for a stint overseas is to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. MSF Australia has noted that this is the best predictor of good performance on an overseas field mission (personal communication). In terms of formal qualifications, a Master (or Diploma) of Public Health is the most relevant. As noted earlier, a Master of Public Health with a global health stream is available in 16 Australian universities and two in New Zealand.17 Some universities and research institutes have special relationships with institutions overseas, for example:

- The University of Melbourne in India and Indonesia

- Deakin University and Burnet Institute in Myanmar

- The University of New South Wales and Burnet Institute in PNG

- Monash University in South Africa

- La Trobe University in China.

If a full-blown postgraduate course is not feasible, many units – such as field epidemiology, health promotion, primary healthcare, maternal and child health, nutrition, communicable diseases, and health in complex emergencies – are available as short courses. One of the most valuable short courses is held by the University of Melbourne’s Nossal Institute at the Jamkhed PHC site in India.18

The Global Health Gateway website provides useful advice on how to decide what and where to study, and displays upcoming courses. AUSMAT provides short training courses for medical professionals who are registered with the program. Red R Australia offers a range of short courses, such as Essentials of Humanitarian Practice and Personal Safety, and Security and Communication.19 Torqaid, based in Torquay, Victoria, regularly publishes a useful Australian aid resource training guide.20 Other useful preparation would be undertaking a short diploma course in relevant fields such as paediatrics, obstetrics and emergency care.

Likely employers

First experiences are often gained through working in a humanitarian emergency. The most likely agencies in Australia to recruit medical practitioners are MSF, the Australian Red Cross, Save the Children and World Vision. Another common avenue is through a volunteer organisation, such as Australian Volunteers for International Development21 or the UK-based VSO International.22 Some Australian faith-based organisations, such as Caritas and Anglican Overseas Aid, have overseas volunteer programs. There is also the UN Volunteers Program, which supports around 8000 volunteers at any one time.23

Australian organisations that recruit medical professionals for long-term positions include the Australian Red Cross, MSF Australia, World Vision, CARE, Marie Stopes International and Save the Children. A number of overseas organisations such as the US-based International Rescue Committee often recruit Australians. Online job networks include the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) Job Network24 and the social enterprise Devex.25 Faith-based organisations such as the Christian Medical Fellowship list vacant positions in mission hospitals.26

Finally …

Technical qualifications aside, essential qualities include cultural sensitivity, and an ability to live and work in a team in remote and resource-poor settings. A decent sense of humour also helps, as does the discipline to take time off in stressful situations to avoid burnout.

Author

Michael J Toole, MBBS, DTM&H (London), Deputy Director for International Health Strategy, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, VIC; Adjunct Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC. toole@burnet.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.