There is broad support for general practitioners (GPs) taking an active role in advance care planning (ACP), given their person-centred approach, long-term relationships with patients and families, and role as care coordinators.1,2

Best practice ACP explores a patient’s values and goals, and elicits and documents preferences in case of a time when they are unable to make or communicate medical treatment decisions.3 Research suggests ACP can be empowering for patients and their families,4 increasing care satisfaction5 and improving bereavement outcomes for family members.6,7 However, GPs experience challenges in negotiating end-of-life decision making, including:8,9

- managing the values and preferences of family members

- worrying about negative impacts on the doctor–patient relationship

- fearing conflict and legal disputes.

In this article, we explore the unique skill sets of professional third-party mediators, illustrate how mediation concepts might be employed in general practice, and present a tool that may assist GPs in managing ACP discussions.

Mediation

Mediation is ‘a process in which participants, with the support of a mediator, identify issues, develop options, consider alternatives and make decisions about future actions and outcomes’.10 Mediation has received some attention in the health literature,11 though mostly as a means of resolving disagreements rather than a way of proactively eliciting values and goals and pre-empting conflict.

The core of the mediation approach is interest-based negotiation, a key principle of which is differentiating between positions and interests.12 Interest-based negotiation proposes that beneath a person’s stated preference or position (eg ‘I don’t want to be resuscitated’) lie a number of interests that explain why a person holds that position (eg ‘I am suffering too much and no longer wish to live like this’).

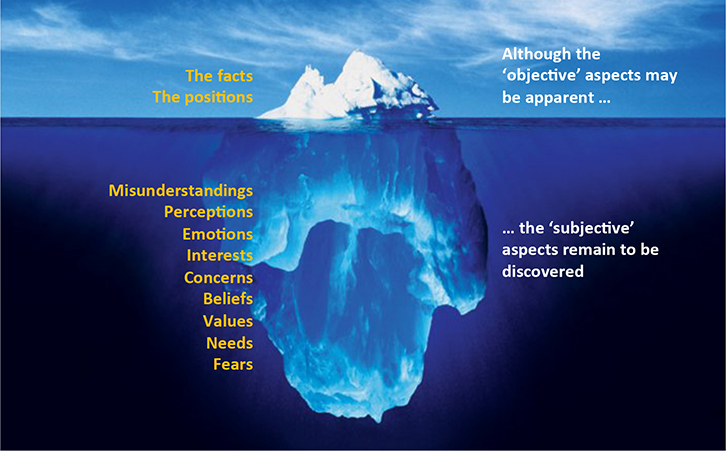

Interests may be connected to a patient’s disease or practical situation,13 but are also motivated by deep human needs and emotions (eg fear, love).12 By eliciting interests, GPs can better understand the hidden factors driving patients’ and their families’ positions (Figure 1). Through this approach, the GP can model a collaborative approach to decision making, reduce the risk of miscommunication, and negotiate agreement and commitment to the ACP process.11 Additionally, we argue that by understanding the interests of other key people in a patient’s support network, patient autonomy can be promoted, and the ACP is more likely to be smoothly implemented.

|

Figure 1. Positions and interests

The iceberg image illustrates how interests typically exist ‘beneath the surface’ and influence a person’s stated position |

A fundamental platform for interest-based negotiation is open disclosure by all parties of relevant interests that might inform decision making. Importantly, doctors also have other interests

(eg professional, ethical, personal). Unlike a neutral mediator, for whom involvement is limited to the period of negotiation, with no investment in any particular outcome, GPs will have ongoing relationships with patients and their family, and may be the doctor enacting decisions made in an advance care plan. The benefits of GPs sharing their own interests include strengthening the doctor–patient relationship, establishing a shared understanding of professional obligations, and minimising legal risk.

We illustrate these concepts through the case of Ellen (pseudonym), her GP and children. Ellen’s quoted material is drawn from a research interview (methods and ethical approvals described elsewhere).14 The perspectives of the GP and children are elaborated on the basis of the authors’ experience.

Ellen

Ellen is 83 years of age and lives alone in her family home. She has emphysema, requiring home oxygen, and is wheelchair-bound due to pain from arthritis. Ellen’s husband, Mick, is deceased. Ellen understands the seriousness of her emphysema and that it is incurable. She finds satisfaction in her life and strongly values her independence.

Four months ago, Ellen was hospitalised with pneumonia and required non-invasive ventilation and intensive chest physiotherapy. After discharge she saw her GP, whom she trusts:

Well, we decided that because I have so many illnesses, that if I had a heart attack and I passed on, well they oughtn’t try to resuscitate me. Because I’d be coming back to a lot more pain and suffering. I definitely don’t want life support as far as I’m concerned. I could go tomorrow, so that’s why I made the decision not to be resuscitated, but at that stage, I didn’t discuss it with my family. I was in the doctor’s office, I talked it over with him. He said he’d make a note of it at this stage.

Despite Ellen’s clear views, she is unwilling to formally document her preferences for fear of upsetting her family:

When I did mention it, it didn’t go down well. My family isn’t very happy about it. It’s more my daughter is the one that’s upset, more than my son. So where it’ll finish up I have no idea. I don’t want to make my family miserable by making a decision [writing an advance healthcare directive].

She spoke of the ‘need to discuss things more’, but was uncertain as to what exactly was upsetting her children:

I presume the thought of it – they just don’t want to face it if I die. They don’t want me to suffer either, but at the same time they think that if I was brought back that I may have several more years of good life. It’d really take a case of the doctor and all the family all getting together at one time and we’d discuss it, but my family’s going in so many directions.

Ellen’s GP (Dr Jones)

Dr Jones has cared for Ellen for years. He was also the GP for Mick prior to his death two years ago, and assisted him in making end-of-life decisions. This led to conflict with Ellen and Mick’s daughter (Joanna), who was upset about treatment withdrawal. While Dr Jones is committed to respecting Ellen’s wishes, he is uncertain about her prognosis, and hence uneasy about her future medical care. He is pressed for time and wary of the prospect of disputes that might damage his reputation.

Ellen’s daughter (Joanna)

Joanna is a teacher with grown children. She believes the withdrawal of treatment during the final stages of her father’s life contributed directly to his death. She suffered from depression following this and was estranged from Ellen for a period. Ellen’s hospitalisation shocked Joanna, as she had not understood the fragility of her mother’s health. She has since become closer to Ellen again. She has a difficult relationship with Dr Jones and previously threatened legal action over Mick’s care.

Ellen’s son (Peter)

Peter is a nurse and has been Ellen’s carer over the past two years. He is fatigued because of commitments to his children, partner and mother. He believes his father received appropriate end-of-life care, but cannot manage the family conflict around this or facilitate discussion about Ellen’s wishes.

Using mediation to facilitate discussion

In this case, a number of factors indicate the potential benefits of an interest-based negotiation approach to facilitate ACP discussion. These include:

- Ellen’s uncertain prognosis

- the range of different treatments and treatment settings available

- previous history of dispute in treatment decision making within the family unit

- Ellen’s indication that she needs assistance in promoting her own treatment wishes among her family members.

Table 1. Components of an interest-based negotiation

|

| Relationship |

Who is connected to the patient?

What is the nature of these relationships?

Who has an interest in this decision?

Who needs to be here? |

| Communication |

Are there notes from any previous conversations?

What are the relevant medical facts?

What medical records are required? |

| Interests |

What are the goals, needs, concerns and fears for all concerned?

Which of these interests are shared? |

| Options |

What actions best serve the patient’s interests and autonomy? |

| Standards |

What legal, ethical or professional standards impact on options and decisions?

What cultural or familial expectations impact on options and decisions? |

| Alternatives |

What other options are available? |

| Commitments |

Can we agree and can we document the outcome? |

Table 1 illustrates the components of interest-based negotiation.12 In this article, we emphasise the third step – eliciting interests. Readers will be familiar with steps one and two through teachings in difficult consultations (eg clinical practice guidelines15 and SPIKES method16). Eliciting interests and identifying shared interests is a platform for discussion about the options, standards, alternatives and commitments that are part of negotiating agreement.12

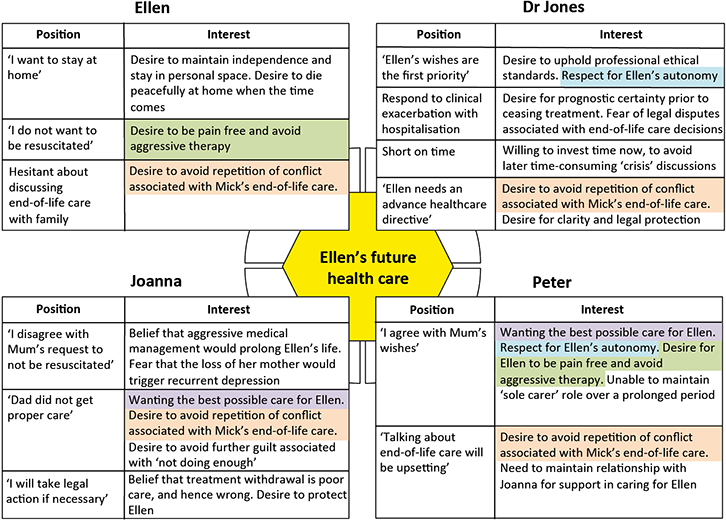

Prior to eliciting interests, the GP should establish agreement about the goals of the discussion. Figure 2 shows a mapping tool that may assist in aligning participants around a goal, and charting positions and interests. Importantly, this tool illustrates how a number of participants share common interests despite having differing positions. Identification of these common interests can be used in discussions to establish agreement and commitment to ACP.

|

Figure 2.

Example positions and interests

Mapped from an ACP discussion between Ellen, Joanna (daughter), Peter (son) and Dr Jones, using an interest-based negotiation approach. Highlighted sections indicate areas of common interest. |

The GP might introduce the tool by emphasising the goals (eg ‘We’re here because we care deeply that Ellen receives the best possible care’) and take the opportunity to disclose his own interests (eg ‘As Ellen’s GP, I have some professional obligations that I’d like you to know about’). The complexity of a family-based discussion results in part from the additional positions and interests present around the table. The mapping tool is particularly useful in such situations, and could be promoted as a way of maintaining focus on the discussion goals, ensuring all participants are heard and understood. Filling in the mapping tool provides participants (including the GP) with the opportunity to reflect on their own interests and creates a point of visual focus during difficult moments in the discussion. This process can develop a sense of affiliation between the participants – a key factor in maintaining open communication and collaborative decision making.12 Table 2 illustrates some techniques and phrases that may assist in eliciting interests and overcoming ‘communication blocks’.

Working from areas of shared interest (eg desire to avoid repetition of conflict associated with Mick’s end-of-life care) provides a starting point for exploring options, understanding and alleviating specific concerns, and establishing agreement and commitment to the ACP.

Table 2. Techniques for eliciting interests and overcoming blocks in communication

|

Eliciting interests: Simple phrases can be used to elicit participant interests. For example,

‘What is most important to you now?’ or ‘When you think about the future, what worries you?’ |

| Acknowledging emotions: At key times, it may help to acknowledge emotions (eg ‘I can see that you’re upset’). This can validate the participant’s perspective and enable them to explain the concern that is driving the emotion. |

| Checking for information gaps and/or misunderstandings: Exploring the interests that underlie positions can reveal misunderstandings that can be easily addressed. |

| Engaging a second opinion: If disagreement about clinical aspects persists, it may be helpful to engage another health professional (eg nurse or a medical colleague). Ideally, this person will be able to offer ‘live’ input at the time of the discussion. In terms of Ellen’s ongoing care, such a process may contribute to greater collaborative decision making, setting up what mediators might call ‘a culture of agreement’. |

| Identifying ‘achievable’ and ‘reach’ goals: In the case of Ellen’s care, it is an achievable goal to negotiate agreement on Ellen’s ACP so that she can avoid burdensome treatments such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation. On the other hand, Ellen’s goal of dying at home may depend on a number of factors, including the capacity of her family and GP to support her in this way. This could be considered a reach goal. |

| Refocusing on the goal of the discussion: At key times during the discussion, it can be helpful to reinforce the central goal (eg ‘We’re all here because we care deeply that Ellen receives the best possible care’). The mapping tool can assist in keeping participants focused. |

Conclusion

By eliciting the interests of key people involved in Ellen’s care, the GP can develop an approach to ACP that promotes patient autonomy while remaining family-centred. By disclosing relevant personal interests, the GP may also establish deeper trust with patients and their families, and increase the likelihood of an advance care plan being smoothly implemented when required. While this approach requires the GP to invest time, we suggest that such time is well spent in terms of averting future disputes. Selective use of this strategy, along with growing political momentum towards specific Medicare funding for ACP discussion,17 makes interest-based negotiation a feasible approach to ACP in general practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient, whose situation provided inspiration for this piece of work.

Authors

Craig Sinclair PhD (Psych), Research Fellow, Rural Clinical School of Western Australia, University of Western Australia, Albany, WA. craig.sinclair@rcswa.edu.au

Catherine Davidson BA, LLB, Accredited Mediator (LEADR), Catherine Davidson Mediation Services, Sydney, NSW

Kirsten Auret MBBS, FRACP, FAChPM, Associate Professor, Rural and Remote Medicine, Rural Clinical School of Western Australia, University of Western Australia, Albany, WA

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.