Case study

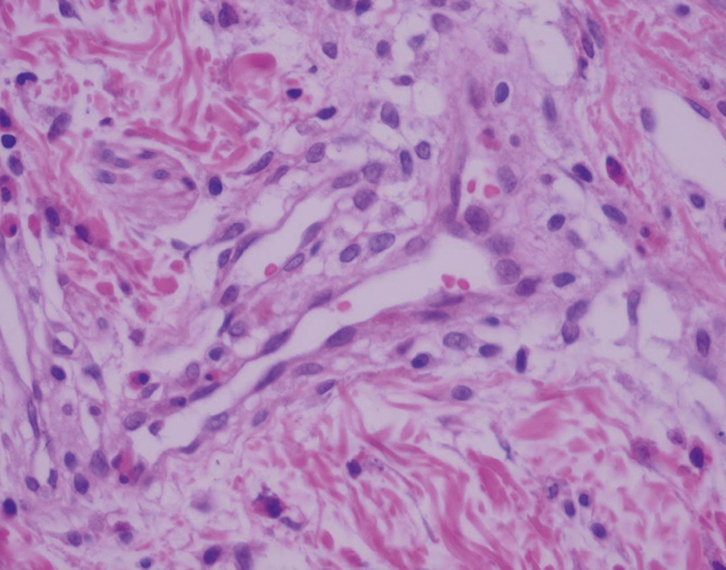

A male infant, 4 months of age, presented with tan-brown, ill-defined macules measuring 0.5–1.5 cm, involving most parts of the body (sparing the face, palms and soles), which had appeared 2 months prior to the consultation (Figure 1). The lesions were asymptomatic and exacerbated by strong crying. An urticated plaque was noted after rubbing a lesion. A skin biopsy was taken, and histopathology revealed a perivascular infiltrate of mast cells and some eosinophils (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Disseminated, tan-brown macules |

|

Figure 2. Skin biopsy showing perivascular infiltrate of

mast cells and eosinophils |

Question 1

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 2

What is the epidemiology of this disease?

Question 3

What is the clinical presentation?

Question 4

Which systemic signs and symptoms have been described?

Question 5

How is the diagnosis made?

Question 6

How would you treat this condition?

Question 7

What is the prognosis?

Answer 1

The diagnosis in this case is urticaria pigmentosa, which is also known as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis and is considered a type of mastocytosis. It includes a heterogeneous group of disorders characterised by abnormal accumulation of mast cells in many organs (eg skin, bone marrow, liver, spleen and lymph nodes; Table 1).1 Urticaria pigmentosa is considered the most reported form of mastocytosis, and accounts for 70–90% of paediatric mastocytosis in previous studies.2 The other defined forms of peadiatric mastocytosis are mastocytoma and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis.2–5

Table 1. World Health Organization classification of mastocytosis, 20084,8

|

Variants

|

Subvariants

|

|

Cutaneous mastocytosis (CM)

|

Urticaria pigmentosa (UP) (maculopapular)

Diffuse CM (DCM)

Mastocytoma of the skin

|

|

Indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM)

|

*Smoldering SM

Isolated bone marrow mastocytosis

|

|

Systemic mastocytosis with an associated clonal haematologic non-mast cell lineage disease (SM-AHNMD)

|

Acute myeloblastic leukaemia (SM-AML)

Myelodysplastic syndrome (SM-MDS)

Myeloproliferative disorder (SM-MPD)

Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (SM-CMML)

Non-hodgkin lymphoma (SM-NHL)

|

|

Aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM)

|

Lymphadenopathic with eosinophilia

|

|

Mast cell leukaemia (MCL)

|

Aleukaemic

|

|

Mast cell sarcoma (eg larynx, colon, brain)

|

|

|

Extracutaneous mastocytoma (eg lung)

|

|

|

*Smoldering systemic mastocytosis has recently been accepted as a separate category,8 but it was not included as such in the 2008 WHO classification

|

Answer 2

An estimated two-thirds of mastocytosis cases begin in early childhood,5 and present in more than 55% of patients before 2 years of age.4 However, 10% may experience disease onset at 2–15 years of age, and 35% when they are 15 years and older.4,5 Its prevalence varies from 1 in 1000 to 1 in 8000 dermatology patients,6 with higher values (up to 1:500) reported in the paediatric population, and a slight male predominance in the paediatric population.7

Answer 3

Classic paediatric urticaria pigmentosa usually presents before 2 years of age with reddish-brown, non-evanescent macules, affecting the trunk and extremities, but sparing palms, soles, face and mucous membranes.7 Erythema, oedema and blisters may appear. Darier’s sign is usually present with urtication of the lesion after mechanical irritation.8 Paediatric urticaria pigmentosa is usually transient and relatively benign, with spontaneous regression of lesions before puberty.2,3 The incidence of systemic involvement in childhood mastocytosis is unknown, but recent studies have found it may reach up to 30% of cases.9 Conversely, adult mastocytosis more commonly involves extracutaneous sites (eg bone marrow).1,7 More than 95% of adults may present with systemic involvement. Most of these patients will have indolent systemic mastocytosis with abnormal mast cells collection in the bone marrow with no other haematological disease or evidence of end-organ damage.10

Answer 4

Systemic symptoms are associated with mast cell degranulation agents (histamine and tryptase), and include pruritus, flushing, vesicles, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea.3 Malignancy has rarely been reported.2,11

Answer 5

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy might be a helpful diagnostic tool.11

Answer 6

Treatment focuses on avoidance of triggering factors that may activate mast cell production of histamine. These include:11,12

- certain foods (eg crayfish, lobster, cheese, spicy foods)

- medications (eg aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, among others)

- excessive heat (eg overly hot baths).

Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines have proved to be helpful.6,11,12

Answer 7

Paediatric mastocytosis has been considered a benign and self-limiting diseases, with partial or complete resolution in more than 60% of children.5 However, a recent analysis suggests that the size/number of lesions and the presence of systemic symptoms may correlate with progression of the disease.2,5 Although regular follow-up is not mandatory, some authors suggest regular follow-up for severe and symptomatic cases, and follow-up every 2–3 years for asymptomatic children.9

Summary

Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of mastocytosis. Mastocytosis usually presents at birth or early childhood, and may involve only the skin or, less commonly, other internal organs. Diagnosis is clinical, but a skin biopsy may be useful. Prognosis is usually good, and treatment focuses on the avoidance of certain triggers and administration of topical and systemic medications. Appropriate counselling of parents regarding the benign nature of this disease is important as most cases resolve by adolescence.

Authors

Jorge Ocampo-Candiani MD, Dermatology Department Chief, Hospital Universitario Dr José Eleuterio González, Dermatology, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico.

Sandra Cecilia García-García MD, Hospital Universitario Dr José Eleuterio González, Dermatology, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico

Guillermo Antonio Guerrero-González MD, Hospital Universitario Dr José Eleuterio González, Dermatology, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico

Sylvia Aide Martínez-Cabriales MD, Hospital Universitario Dr José Eleuterio González, Dermatology, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.