Heel pain is a vague term describing pain surrounding the calcaneus, most commonly felt posteriorly or inferiorly. Anatomically, the heel refers to the fatty tissue that forms a pad under and around the calcaneus to protect structures of the foot during weight-bearing activity.2 However, patients consider a more broad area as their heel. This review, therefore, will consider the structures that may cause pain from the calcaneus, extending to both lateral and medial perimalleolar regions, the Achilles enthesis and proximal plantar fascia attachment. Most pain arises from pathology in soft tissue structures (tendons, fascia and nerves); apophyses and other sources of bony pain are less common. As with other soft tissue structures, pathology on imaging is not always correlated with pain and a good clinical examination is required to reveal the painful structure. Palpation pain is a poor diagnostic test in isolation, as many structures are painful on palpation without being the cause of symptoms. The history and further clinical examination remain important.

Sources of pain by structure

Tendons

|

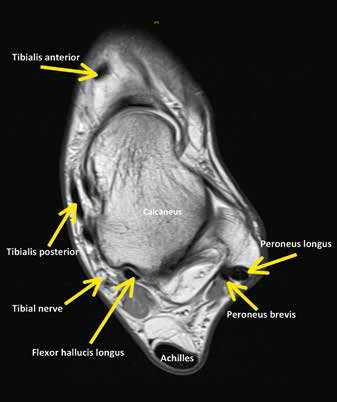

| Figure 1. Relationship of the calcaneus to neural structures and tendons (transverse view) |

The key tendons that may be involved in heel pain are the Achilles tendon at its insertion, flexor hallucis longus (FHL), tibialis posterior and the peroneal tendons (Figure 1). The medial and lateral tendons are surrounded by tenosynovial sheaths that can be irritated by friction or compression at the malleolus. Tibilais posterior pain (tendon and/or sheath) is most commonly seen in older women.3,4 FHL tenosynovitis is seen in younger people, especially dancers because of the repetitive movement of the ankle and foot between extremes of plantarflexion and dorsiflexion.5

The Achilles insertion is a complex structure that includes the retrocalcaneal bursa.6 All insertional pain should be treated holistically as a tendinopathy, as the bursa is rarely affected in isolation.7 The mid-substance and insertional Achilles tendon undergo similar histopathological change.8 Excess compression of the tendon against the superior calcaneus in dorsiflexion is the provocative load; however, a Haglund morphology (a square superior prominence of the calcaneus) is common and complete resolution of symptoms can occur despite the anatomy.9

Peroneal tendinopathy is less common and is seen after acute ankle sprain or provoked by an insufficient retinaculum at the lateral malleolus, again increasing compression and friction loads. The plantar fascia, histologically indistinguishable from a tendon, is also a common source of pain, especially in older women who are more obese.10

Neural sources of heel pain: entrapment and referred pain

Pain from a neural source can mimic soft tissue pain. Neural sources of heel pain may include an entrapment that can occur proximally, for example, in the lower lumbar spine and gluteal region, or distally at the ankle retinacula. The posterior tibial nerve ends deep to the flexor retinaculum, then divides into the medial and lateral plantar (also termed calcaneal) nerves, where it is especially vulnerable. Pain from this source can mimic plantar heel pain.11 Tarsal tunnel syndrome is an entrapment of the posterior tibial nerve under the flexor retinaculum. Rarely, sural nerve symptoms can be related to Achilles tendinopathy, resulting in posterior heel neural signs.

Bone and joints

Calcaneal bone injury is rare in adults but can cause heel pain following either a traumatic fall from a height (fracture) or excessive weight-bearing such as running or marching (bone stress reaction or stress fracture).12,13 Talar and navicular stress fractures are infrequent but considered high risk because of their propensity to progress to full fracture or result in non-union or delayed union,14 which require lengthy periods of non-weight bearing or surgical management. The subtalar joint or the transverse tarsal joint may cause pain due to acute injury or arthritis.

Table 1. Possible structures and sites of pain

|

|

Site/type of pain

|

Common sources of pain

|

Less common sources of pain

|

|---|

|

Posterior

|

- Achilles tendon insertion

- Superficial calcaneal bursa

- Posterior impingement of soft-tissues/os trigonum in active people

- Calcaneal apophysis in adolescents

|

|

|

Inferior

|

- Plantar fascia

- Calcaneal fat pad

|

- Medial or lateral calcaneal nerve, especially as they split from the tibial branch

|

|

Medial

|

- Tibialis posterior tendon and sheath

- Tibialis posterior insertion and apophysis in adolescents

|

- FHL and sheath

- Abductor hallucis

- Deltoid and spring ligaments

- Posterior tibial nerve in tarsal tunnel (is associated with neural symptoms such as tingling)

- Bone: medial malleolus

|

|

Lateral

|

- Lateral ligaments of the ankle

- Sinus tarsi

|

- Peroneal tendinopathy or tenosynovitis associated with subluxation

- Cubometatarsal joint

- Peroneus brevis insertion/apophysis of base of 5th metatarsal in adolescents or after ankle sprain

|

|

Deep, vague pain

|

|

- Bone pain: calcaneus, talus, navicular

|

|

FHL, flexor hallucis longus

|

Sources of pain by site

Differential diagnosis is complex, as there may be pain from more than one structure. The site of pain may be a guide to the structures involved (Table 1) and there are several key clinical history questions that will guide the clinician to the likely source of pain (Table 2). The most important questions to ask are ‘Where is your pain? When did it start and what were you doing when it started?’ Mechanical causes of heel pain are often brought on by a change in activity or a change in shoes. A specific incident or trauma to the region will guide further questioning around the forces and potential sources of pain.

Table 2. Subjective assessment questions to direct clinical reasoning

|

|

Question

|

Common responses

|

Diagnoses to consider

|

|---|

|

Age

|

Young

|

Common: Sever’s disease (calcaneal apophysitis)

Uncommon: calcaneal stress or tumour

|

|

Middle-aged

|

Common: Achilles insertion tendinopathy, plantar fascia pain

|

|

Older

|

Common: tibialis posterior tendinopathy and lengthening

|

|

What aggravates the pain?

|

Mechanical causes (eg walking, running)

|

Insertional Achilles tendinopathy (note, a warm-up phenomenon with activity is reported)

Pain that increases with activity may indicate:

- involvement of sheath (paratendinitis)

- bone (stress reaction or stress fracture)

- sinus tarsi or neural sources (including tarsal tunnel); prolonged standing can irritate tarsal tunnel.

|

|

Non-mechanical

|

Pain at rest should be questioned further in terms of positioning and neural symptoms

Tendon pain at rest is uncommon but pain on rising after sitting is a hallmark sign of tendinopathy

|

|

Was the onset of pain associated with an incident?

|

Yes: change to weight-bearing load

(eg running or footwear)

|

Achilles tendinopathy

Calcaneal bone stress

|

|

No

|

Consider arthritic causes

|

|

Pain behaviour

|

Morning pain and stiffness

|

Achilles tendinopathy, FHL tenosynovitis, plantar fascia pain

Long time to warm up (>60 minutes): consider rheumatological cause

|

|

Night pain

|

Bone stress (eg calcaneal stress or more sinister causes)

|

|

General health questions and red flags

|

Night pain

Other flags such as loss of weight, night sweats, joint pain and swelling

|

Tumour

Consider non-musculoskeletal cause and include rheumatoid arthritis, gout, spondyarthopathies, infection

|

|

Past injury

|

Repeated ankle sprains can commonly cause posterior impingement and sinus tarsi syndromes

|

|

Other

|

Cramping (calf and feet)

|

Vascular claudication

Can be an early indicator of bone stress

|

|

Neural symptoms

|

Sharp pain, burning, ‘pins and needles’ or numbness indicate neural involvement (eg tarsal tunnel syndrome (posterior tibial nerve and branches) present with symptoms in posteromedial ankle and heel and may extend to distal sole and toes)

|

Following a thorough history taking, the potential sources of pain are identified and further objective assessment conducted to confirm the diagnosis (Table 3). Although some diagnoses are uncommon, they are important to recognise. Examples of these diagnoses include Achilles tendon rupture, which can be recent or chronic and presents with pain due to blood pooling distal to rupture, progressive tibialis posterior lengthening, seronegative arthropathies presenting as Achilles insertional tendinopathy, stress fractures, osteoid osteoma and tarsal coalition.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Simmonds’ calf squeeze

With the foot relaxed squeezing the calf should elicit plantar flexion of the foot with an intact Achilles tendon |

Figure 3. Posterior impingement test

Firm and slow compression of the calcaneus into the tibia will cause symptoms |

Figure 4. FHL test

Active or resisted plantarflexion of the great toe in full ankle plantarflexion will provoke crepitus and possible pain |

Table 3. Objective assessment

|

|

Site/type of pain

|

Common sources of pain

|

|---|

|

Observation

|

Skin – colour, bruising, swelling, abrasions, rashes, Achilles tendon swelling / thickening or obvious deformity,

muscle wasting

|

|

Functional – walking

|

Limping, avoiding joint movement or loading

|

|

Calf raise – double or single

|

Should be capable of lifting body weight on each leg at least 10 times. Inability to do this consider Achilles tendon rupture or tibialis posterior tear

|

|

Palpation

|

The sural nerve can be easily palpated lateral to the Achilles tendon with the ankle in dorsiflexion

Sinus tarsi pain can indicate local and subtalar joint synovitis

Plantar fascia attachment on the medial process of the calcaneal tuberosity

Tibialis posterior and FHL tendons posteromedial to medial malleolus

Apophyses such as calcaneal, navicular, base of 5th metatarsal

- Note the Achilles tendon squeeze can be painful when the tendon is not the source of heel pain and is a poor diagnostic test

Sites of bone stress: calcaneal squeeze for calcaneus, dorsal navicular and talar neck

|

|

Muscle strength

|

Resisted inversion in plantarflexion for tibialis posterior

Resisted eversion for peroneals. Observe peroneal tendon does not sublux around lateral malleolus

|

|

Other – special tests

|

Specific tests such as the Simmonds’ calf squeeze test for suspected Achilles tendon rupture (Figure 2)

Posterior impingement test (Figure 3) and FHL testing (Figure 4) should reproduce symptoms

Crepitus and clicking not always associated with symptoms

Gentle palpation of the Achilles during active plantarflexion and dorsiflexion may demonstrate crepitus consistent with Achilles paratendinitis (sheath inflammation)

Tinel’s sign is well described and involves 4–6 taps over the nerve (such as sural or tibial) and should elicit ‘pins and needles’ or tingling

|

|

Neural testing

|

Straight leg raise with bias for peroneal nerve (add adduction, ankle plantar flexion and inversion) or tibial nerve

(add dorsiflexion and eversion)

Commonly – this may not reproduce the pain but an asymmetry can be noted

Seated slump with lumbar kyphosis or lordosis

|

Bony presentations may require imaging when there is a high index of suspicion. Tarsal coalition may present with flat foot and pain, and requires imaging to confirm it, especially if the patient has a family history of the condition. Osteoid osteoma should be considered when night pain is reported.

The role of diagnostic imaging in heel pain

Clinical assessment remains the most important diagnostic tool as imaging identifies pathology and structural abnormality. However, tendon and joint pathology can be present without pain. Therefore, pathology on imaging can mislead the clinician into thinking that imaging has confirmed the source of pain. Common examples include the presence of an os trigonum and heel spurs at the attachment of the plantar fascia and peroneal tendon pathology, seen as an increased signal on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is common following an ankle inversion injury. Posterior ankle impingement syndrome and subtalar joint synovitis following an ankle sprain is a more likely source of pain (Figure 3). Similarly, pathology in the retrocalcaneal bursa and Achilles tendon, together with a Haglund morphology can be present in people who are

pain-free.15

Treatment of heel pain

An overview of the available evidence and expert clinical opinion for the conservative treatment of common causes of heel pain is not intended to be comprehensive or prescriptive (Table 4). Clinical experience, for example neural mobilisation techniques,16 has been included as there is a lack of published evidence for efficacious treatment. Furthermore, the decision to include analgesia or anti-inflammatory medication is discussed only where its use has been shown to be detrimental or to have an off-label effect (eg heparin-based treatments for paratendinitis17 and the polypill).18 Consideration of the kinetic chain is vital for the successful rehabilitation of many conditions and is outside the scope of this paper. Referral to allied health professionals such as physiotherapists or podiatrists may be necessary.

Table 4. Evidence-based and clinical opinion for management by cause

|

|

Cause of pain

|

Recommendations

|

No evidence or not advised

|

|---|

|

Achilles tendon insertion pain or retrocalcaneal bursitis

|

Heel raises in shoes or added externally to shoes

(to reduce compression at the Haglund prominence)

|

Avoid stretching and the eccentric heel drop program (due to compression). May be completed to plantargrade

|

|

Graded strength rehabilitation from flat ground into plantar flexion

|

Intra-tendinous injections

|

|

Other: polypill (ibuprofen, epigallocatechin gallate and doxycycline)18

|

Rest/ice/anti-inflammatory medications have limited efficacy: there is no evidence of inflammation in chronic tendinopathy

|

|

Posterior impingement syndrome

|

Calf strengthening – single leg heel raises, 25+ repetitions in a painfree range of motion in younger people

Manual techniques that involve sub-talar joint distraction

|

Compressive positions or forced ankle joint plantar flexion

|

|

FHL (usually tenosynovitis)

|

Calf strengthening – single leg heel raises, 25+ repetitions in a pain-free range of movement in younger people

Hirrudoid/diclofenac gel wrap – good clinical results with physiological justification (heparin based treatments block the formation of fibrin associated with crepitus17

|

Eccentric exercises and stretches in full dorsiflexion or heel off step

|

|

Neural – entrapment (including tarsal tunnel)

|

Neural mobilisation

|

Neural tension exercise

|

|

Check for direct compression (eg footware)

|

|

|

Treat underlying pathology of FHL

|

|

|

Plantar fascia pain

|

Taping and orthotics may offer relief

Strengthening of the foot intrinsics, calf and kinetic chain

Low height isometric heel raise sustained hold

|

|

|

Tibialis posterior tendinopathy (may be tenosynovitis)

|

Taping and orthotics

Heel raise

Strengthening in good ankle alignment

|

Eccentric exercise often increases the friction around the medial malleolus and exacerbates symptoms

|

|

Calcaneal bone stress

Talar stress fracture

Navicular stress fracture

|

Reduction in load and may require non-weight bearing

|

|

|

Apophysitis

|

Reduction in load

May benefit from a heel cup with heel raise in shoes to reduce traction of the apophysis

Taping and orthotics

Graded strengthening program

Improving muscle compliance of the gastrocnemius, soleus and tibialis posterior

|

Though stretching is regularly recommended, initially it is painful especially if felt at the insertion

|

|

FHL, flexor hallucis longus

|

Conclusion

Heel pain is usually of mechanical origin and the most valuable approach for the clinician is to use the site of pain to narrow potential diagnoses. Imaging can assist, however should not replace clinician assessment. Treatments vary with presentation and require thoughtful prescription.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.