Patients with chronic venous leg ulcers are increasingly being seen in primary care and hospital settings. In general practice, the most common chronic wounds seen are chronic venous leg ulcer, which are managed most often by the general practitioner (GP) and, in some cases, by their practice nurses.1,2

Effective treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers is time-consuming and depends on appropriate assessment, which includes examination of the ulcer and the patient. Surveys of GPs about their knowledge of and attitudes to the care of leg ulcers have been reported.3,4 These surveys have identified a lack of access to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines as a significant barrier in improving the care of leg ulcers.3,4 Although there are several published guidelines for the management of chronic venous ulcers5,6 and other types of leg ulcers7, they are not suitable in a busy general practice. Sadler et al1 indicated that the available ‘traditional leg ulcer guidelines may be not be appropriate or acceptable in general practice’. Weller and Evans reported that a survey of practice nurses who manage venous leg ulcers in the community identified the need for ‘simple guidelines for GPs for leg ulcer management’ to improve patient care.2 A practical guideline incorporating analytical and non-analytical processes of clinical reasoning, which may be called strategic clinical reasoning, would therefore be useful in the primary care management of chronic leg ulcers, 90% of which are due to venous and/or arterial causes.8

This practical guideline, using the A2BC2D approach incorporating the TIME concept of wound bed preparation,9,10 is intended for GPs and practice nurses in a busy clinic. It is a short, evidence-based practical guide covering examination, diagnosis and initial management of chronic venous leg ulcers, which are the most common entity. The need and indications for referral to a specialist clinic has also been included in this guideline.

A2BC2D approach

A1. Assessment of the wound

The first step is to determine the location, size and number (in case of multiple) of the wound(s). A digital photograph with a disposable ruler adjacent to the ulcer is highly recommended.11 This is followed by describing the extent of necrotic tissue in the wound bed (T), presence of inflammation or infection (I), evidence of any surrounding maceration (M) and the edge (E) of the ulcer, noting the presence or absence of epithelialisation. This forms the acronym TIME, which was described in 2003 and remains at the forefront of chronic wound management (Table 1).10 The application of the TIME concept with modification to provide an individualised management plan12,13 is described below under A2.

Table 1. Local condition of the leg ulcer

|

|

Wound score

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

|---|

|

T – presence of necrotic tissue

|

0%

|

30%

|

60%

|

90%

|

|

I – presence of inflammation/infection

|

Absent

|

Contamination

|

Colonisation

|

Infection

|

|

M – presence of maceration

|

Absent

|

Little exudate

|

Much exudate

|

Smelly exudate

|

|

E – absence of epidermis reconstruction

|

0%

|

30%

|

60%

|

90%

|

|

Reproduced with permission farom John Wiley and Sons from Ligresti C, Bo F. Wound bed preparation of difficult wounds: an evolution of the principles of TIME. Int Wound J 2007;4:21–29.

|

|---|

Assessment of the arterial supply to the leg is performed with combined clinical features and measurement of the ankle brachial index (ABI) with a pocket Doppler monitor, which is known to have high specificity in detecting arterial occlusion.14 Dry, hairless skin with reduced or absent pedal pulses indicates an arterial cause of the ulcer. An ABI of ≤0.8 requires further investigation with duplex scan to confirm the presence and degree of arterial occlusion. It is important to remember that an elevated ABI (≥1.2) may be due to a calcified artery. In the context of an elevated ABI and clinical features supporting an arterial ulcer, the patient should be further investigated for peripheral arterial disease. A brief examination would confirm or exclude the presence of chronic venous stasis (lipodermatosclerosis, varicose veins, cutaneous phlebectasia) and any lymphoedema.

|

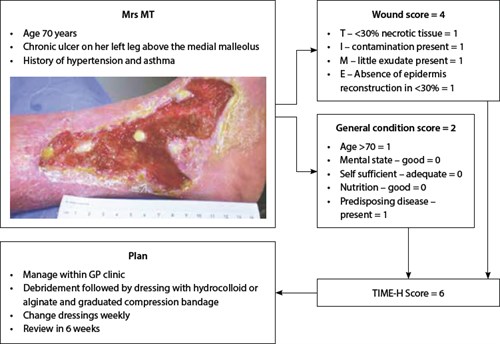

| Figure 1. Case study illustrating management principles using TIME-H score |

Testing for sensation under the great toe, first and fifth metatarsal bone can assess for diabetic neuropathy. This needs to be done with a 10-g monofilament nylon, avoiding areas of callosities. In the event of neuropathy with foot ulcers, referral to a specialist is advisable, where facilities allow for a total contact cast to be applied. This will allow for pressure of loading and aid in achieving healing. Diabetic foot ulcers with features of infection require prompt treatment with a combination of a topical antimicrobial dressing and systemic antibiotics.15

Atypical leg ulcers are characterised by more proximal locations and may occur despite palpable distal pulses. They are associated with cutaneous manifestations such as macules, purpura, nodules and livedo reticularis.16 When an atypical leg ulcer is suspected, the patient should be referred to a specialist wound clinic for appropriate investigation and treatment.

A2. Assessment of the patient

This is an essential part of the management, as most chronic venous leg ulcers are not an isolated disease but the manifestation of an underlying problem.17,18 History of comorbidities such as hypertension, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, asthma, obstructive airway disease, inflammatory bowel disease, present or past history of cancer, anaemia, malnutrition and lack of mobility should be noted.

Ligresti and Bo12 proposed the TIME-H concept to define prognosis of chronic wounds by accounting for the local conditions of the wound (Table 1) and the general condition of the patient (Table 2). They assigned a numerical value to each parameter to develop wound and general condition scores. When combined, the two scores provide a ‘healing score’ for the purpose of predicting wound healing time and planning an individualised treatment protocol (Table 3, Figure 1).

This is useful for setting goals of care, and determining prognosis and whether to refer to specialists, who may consider adjunctive treatment measures such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy and prescribing pentoxyphylline19,20 or other measures.

Table 2. General condition of the patient

|

|

General condition score

|

0

|

1

|

|---|

|

Mental state

|

Good

|

Poor

|

|

Self-sufficiency

|

Adequate

|

Very poor

|

|

Nutrition

|

Good

|

Poor

|

|

Age in years

|

<70

|

>70

|

|

Predisposing disease

|

Absent

|

Present

|

|

Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons from Ligresti C, Bo F. Wound bed preparation of difficult wounds: an evolution of the principles of TIME.

Int Wound J 2007;4:21–29.

|

|---|

Table 3. Interpretation of TIME-H scores

|

|

TIME-H Score

|

|---|

|

Certain healing

|

0–6

|

|

Uncertain healing

|

7–12

|

|

Difficult healing

|

13–17

|

|

Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons from Ligresti C, Bo F. Wound bed preparation of difficult wounds: an evolution of the principles of TIME.

Int Wound J 2007;4:21–29.

|

|---|

B. Best dressing to choose

Principles in choosing the appropriate dressings are to:

- ensure optimum moisture balance (ie neither too moist, nor too dry)

- control/eradicate biofilm

- prevent adherence of the dressing with the wound bed

- control pain

- provide pressure relief for ulcers that are from pressure injuries.

Marketing of wound dressings products is often based on high levels of advertising rather than high levels of evidence of their effectiveness.21 Hence, the choice of dressing should be made on the basis of the above principles and their cost.22,23 In a general practice setting it would be useful to keep some of the common dressings in the treatment rooms. The indications and approximate costs of the dressings are listed in the Table 4.

Before applying a dressing, debridement of the wound bed must be considered. Frequent mechanical debridement of a chronic wound has been well documented to achieve faster healing.24 This can be performed under topical anaesthesia in the practice location.25

Table 4. Common dressings33

|

|

Dressings type

|

Indication

|

Cost* ($)

|

Examples

|

|---|

|

Alginate

|

Wounds with heavy exudates

|

8.08

|

Algisite

Kaltostat

Sorbsan

|

|

Cadexomer iodine

|

Wounds with malodorous exudate

|

44.05

|

Iodosorb

Inadine

|

|

Foam

|

Wounds with mild to moderate exudates

Wounds in granulation stage

Surface epithelial wounds in the setting of sensitive skin

Ulcers in the terminal stage of clearing process

Non-infective

|

7.69

|

Allevyn

Biatain

Hydrasorb

|

|

Hydrocolloid

|

Chronic wounds with mild to moderate exudates

|

7.33

|

Comfeel

Duoderm

Hydrocoll

|

|

Hydrofibre

|

Wound with heavy exudate

|

9.57

|

Aquacel

|

|

Hydrogel

|

Dry wounds with covering fibrin and necrotic tissue

|

8.10

|

Aquaclear

Intrasite Gel

|

|

*Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme cost for a single dressing closest to the size of 10x10cm34

|

|---|

C1. Consider compression bandaging

The application of a graduated compression bandage (two, three or four layers) or stockings after ensuring that there is adequate arterial supply has been proven to be the most effective management of chronic venous leg ulcers.26 Unfortunately, studies indicate that this is often not practised outside dedicated wound care services and is often rarely mentioned in general practice. Weller26 reported the improved healing of venous ulcers along with reduction of bandage cost and nursing time following the application of a three-layer bandaging/stocking system.

C2. Concern of the patient

|

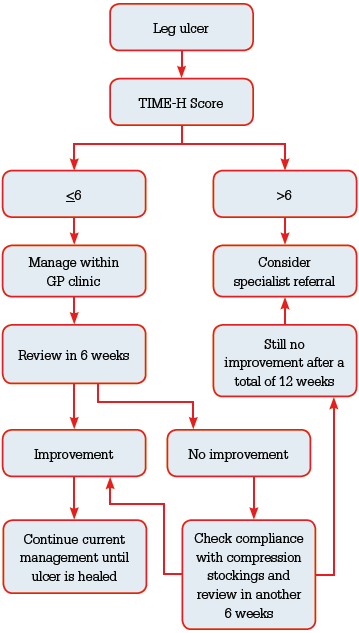

Figure 2. Approach to management of leg ulcers in

general practice |

The most common concern that patients express is pain during change of dressings or at night. This is followed by the offensive odour from the wound exudate, which often leads to social isolation.27 Effective pain management depends on the nature of the pain – nociceptive (occurring in the wound intermittently especially during change of dressings) or neuropathic (arising from ischaemia to the sensory nerves). Increasing pain in a chronic wound has been suggested as a most useful and reliable clinical indicator of infection.28,29

A malodorous exudate can be managed with a combination of adequate debridement, a short course of antibiotics (topical or systemic) and dressings. The recent trend to use expensive silver-based dressings is not justified by the available evidence.30 There is some evidence to use cadexomer iodine dressings in such cases.31 Patients with venous ulcers often complain of irritable and itchy skin around the ulcer, which is due to stasis dermatitis or eczema. A moderately potent topical steroid such as triamcinolone ointment around the ulcer is recommended.

D. Documentation

Documentation of the examination findings, wound scores and management plan for future reference is the final step of the consultation process.32

Referral to specialist

Finally, specialist referral should be considered when:

- there is suspicion of malignancy

- there are clinical features of peripheral arterial disease

- there is an atypical leg ulcer

- an ulcer does not improve or increases in size despite management in the primary care setting

- TIME-H score is >6

- a patient with a venous ulcer is unable to tolerate compression due to pain.

Competing interests: Sadhishaan Sreedharan has shares in Avita Medical.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.