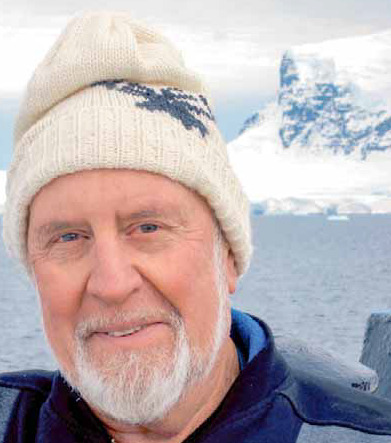

Universal practitioner

Dr Kamien became one of the oldest doctors to work on polar expeditions when he started at the age of 70.

Emeritus Professor Max Kamien’s career in general practice has allowed him to advocate for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Certain Australians will likely always be synonymous with their profession – Don Bradman and cricket, Banjo Paterson and poetry, Cate Blanchett and acting. When people think about who is associated with general practice, especially in Western Australia, few could look past Emeritus Professor Max Kamien, an RACGP Life Fellow who has dedicated more than five decades to Australian and international medicine.

Dr Kamien’s lifelong devotion to the general practice profession, and his passion for medical education and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health are just some of the reasons he was awarded the RACGP’s 2015 Rose-Hunt Award. But this accolade was far from his first.

Dr Kamien was presented with the Australian and New Zealand Association of Medical Education Award for Research in 1995, the Louis Ariotti Award for Rural Health Research in 2000, named a Western Australian Citizen of the Year in 1998, made a Member in the Order of Australia for his services to medicine, particularly in medical education, Aboriginal health and rural medicine, in 1999, and was a Western Australian fi nalist in the Australian of the Year Awards in 2009.

But receiving the Rose-Hunt, the RACGP’s highest honour for a career in general practice, holds a special place for Dr Kamien.

‘When one is in his 80th year, the time for recognition of any achievements has usually long passed, so the Rose-Hunt Award was completely unexpected. It is nice that someone thinks highly enough of me to go to the considerable trouble of putting in a nomination for me,’ he told Good Practice. ‘I put a fair bit of effort into whatever I do, but I don’t expect to get any recognition for it.’

Dr Kamien’s involvement with the RACGP began when he sat on the Western Australia Faculty Board from 1977–88. He later became the Western Australia state archivist, Corlis Fellow and Provost and is now Chair of the National Archives Committee.

‘I was fairly late to the RACGP. I was 40 years old before I joined,’ he said. ‘As I got older, I put my hand up and said that I would be interested in being the state archivist because I had an interest in medical history. Then they were searching around for a wise old man to be the Provost, so I said I would do that as well.

‘I have really enjoyed working with the Western Australia Faculty, particularly the staff members. I go in fairly regularly just to remind them of what a good job they are doing.’

Early beginnings

Dr Kamien grew up in Perth during the Second World War and was accepted into the academically-selective Perth Modern School during his secondary years. Despite the lack of a medical school in his home state, he remained determined to pursue his dream of a career in medicine.

‘Because Western Australia did not have a medical school, those who wanted to study medicine had to move to South Australia,’ Dr Kamien said. ‘When I finished my fourth year of medical school in Adelaide, the Western Australian medical school had just begun so I transferred back to Perth.

‘Those were the golden days of the medical school. There were more teachers than there were students, which enabled me to form really close relationships with many of those teachers. And I still maintain relationships with many who are still with us.’

Dr Kamien graduated from medical school in 1960 and completed his residency at Fremantle Hospital and Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital. He then embarked on three years of travelling and practising medicine in some of the more far-flung corners of the world.

‘I went to Papua New Guinea for a year, worked as a volunteer locum for the Save the Children Fund in South Korea and Jordan, and I had a stint with the Red Cross in Nepal, working with Tibetan refugees.’

It was during this time of international travel that Dr Kamien met his future wife, Jackie.

Max talks of some unusual situations during his time in PNG

‘I was in Israel administering anaesthetics in a hospital when I decided I needed to learn Hebrew in order to converse with my patients,’ he said.

‘I was at the bottom of the class in the language school and the teacher put me with the lady who was the top of the class. We ended up getting married and she has been teaching me and our three children ever since.’

When his travels ended, Dr Kamien settled in the UK with the intention of training and working towards becoming a physician.

‘I couldn’t get a job because, at the time, my travels made me seem quite unreliable,’ he said. ‘Eventually, I got a job in child psychiatry. After that I got very good jobs and I had a really good time learning in England.

‘I ended up completing diplomas of psychological medicine and child health and was one of 50 candidates from a field of 750 who passed the Royal College of Physicians of London exam. It was the only exam that I ever topped.’

While Dr Kamien was working in gastroenterology at the Royal Postgraduate Hospital in London in 1969, a psychiatric research position in the New South Wales town of Bourke became available. A remote town with a large Aboriginal population situated approximately nine hours north-west of Sydney, Bourke is where Dr Kamien kickstarted his Australian general practice career. ‘The very first day that I was in Bourke, I went to the Bourke Aboriginal Reserve where the first child that I saw had kwashiorkor, a protein-deficiency disease,’ he said. ‘Gradually, I became the GP for the Aboriginal community.

‘I could see that just being their doctor was really not enough. I wanted to do more and I came up with the idea of being a doctor who was also an agent of social change.’

General practice advocacy

Dr Kamien has been credited as a pioneer who introduced a number of different services to the people of Bourke, including inexpensive housing and various types of specialist care. When he first arrived in Bourke, Dr Kamien found that up to quarter of the Aboriginal children had trachoma, a bacterial infection of the eye.

‘I went to Sydney looking for an architect interested in low-cost housing with hot water and protection from flies. I was also looking for an eye doctor and I found Fred Hollows,’ he said. ‘He came up to Bourke several months later and it was in a little place called Enngonia, 100 km from Bourke, that he thought up the idea of a National Trachoma Campaign.

‘This morphed into a worldwide organisation [the Fred Hollows Foundation] that has reduced blindness in over a million people. The saying “from little things big things grow” could not be truer than when applied to the Fred Hollows Foundation.’

Dr Kamien believes GPs’ advocacy role should extend beyond the walls of the practice and encourages more young doctors to get involved with health initiatives in their community.

‘One of the ways I thought about getting rid of infective skin disease among the Aboriginal population in Bourke was to get the kids into a chlorinated swimming pool,’ he said. ‘But Aboriginal kids back then did not go to the swimming pools because they felt discriminated against.

‘So I decided to start a water polo association for Aboriginal kids and they then went to the swimming pool. I really thought this is one direction that general practice ought to explore.’

Dr Kamien left Bourke after 3.5 years to be with his ill mother in Perth. He soon got his first taste of academia when he was appointed a senior lecturer in medicine at the University of Western Australia.

‘In comparison with Bourke, teaching hospital medicine was pretty tame,’ he said.

‘It was predictable because you had 15 beds. Five were people with diabetes, fi ve had alcohol problems, four were waiting for aged care accommodation and, once every three months, there would be a patient that required real diagnostic acumen.’

Medical education

Growing up in Perth, Dr Kamien aspired to be a secondary school teacher who specialised in English, physics and tennis. His own educators, however, encouraged him to pursue other career objectives.

‘My teachers took me aside and told me that they didn’t think I’d do very well as a teacher because I would have a lot of trouble with the educational department, and vice versa,’ he explained. ‘I saw a vocational guidance counsellor and he put me through a whole lot of tests and told me I was totally unsuited for medicine, but engineering was my forte.

‘I ended up going against his advice and enrolled in medicine – and probably saved Western Australia from a few tragedies as a result of collapsing bridges.’

Despite choosing medicine over his initial aspirations of the classroom, medical education has always been a significant aspect of Dr Kamien’s career and it remains something about which he is deeply passionate. He believes more medical training should be conducted in general practice, where it can benefit patients and students.

‘I just enjoy medical education. No one had to tell me to do it and I enjoyed that sort of relationship,’ he said. ‘I was aware that since most medicine occurs in general practice that is where some more medical education should take place.’

Dr Kamien was appointed Chair of General Practice and Head of the Department of Community Practice at the University of Western Australia in 1976.

‘In those days general practice was not accorded the status of an academic discipline. Community practice was to be the new university-based discipline. It was to include general practice, social medicine, epidemiology, the sociology of medicine and medical anthropology, and so on,’ he explained. ‘It was sort of a catch-all and I thought that would really suit me.

‘I saw it as an extension of my explorations into the doctor as an agent of social change.’

Dr Kamien’s much-anticipated Report of the ministerial inquiry into the recruitment and retention of country doctors in Western Australia (also known as the Kamien Report) was published in 1987 and played a major role in policies around general practice in WA’s rural and remote communities.

‘The report found that a student’s chances of getting into medical school from a rural high school were close to nil, and the chances of getting in as an Aboriginal person were nil,’ Dr Kamien said. ‘My recommendations for affirmative entry of such students to medical schools were widely resisted. But they have been proven to be right and the action of taking people [into medical school] has produced excellent doctors, many of whom have gone into rural medicine and taken up leadership roles.’

Personal pursuits

While many people choose to slow down past the age of 65, Dr Kamien was 70 when he became one of the oldest doctors to have worked as a medical officer on polar expedition boats in both the Arctic and Antarctic, something he went on to do on seven occasions.

‘I have always been interested in polar exploration and that is sort of a retirement thing that I took up,’ he said. ‘Most of the medical people who go on these boats are young doctors training in emergency medicine, but most of the passengers are closer to my age and they don’t always form a relationship with the young doctors.’

Another of Dr Kamien’s long-held interest lies in writing. His literary pursuits first began when he became the editor of the University of Western Australia’s medical student magazine, The Reflex. He has published more than 200 academic papers and 400 commentaries over the course of his career and continues to write for Australian Doctor.

‘I write a lot about the things I do and see because I need a level of self-deprecating humour to sustain me,’ Dr Kamien said. ‘Good general practice is a hard discipline. I enjoy the long-term relationships with patients and families. I also enjoy the lateral thinking that is often needed to help them solve their problems.

‘I tell medical students and young doctors that medicine is a serious business, but it can also be a lot of fun. If there was a second life, I would do it again.’

By Bevan Wang - originally published in Good Practice October 2015.