Consumer experience is recognised as a central tenet of quality in healthcare.1 A positive consumer experience of a health service can increase the likelihood of following healthcare provider advice, enhance consumer confidence and positively influence subsequent health outcomes.2 A poor experience is associated with diminished health outcomes.3 Measures of patient experience or consumer satisfaction are widely used to ensure that health services are acceptable and responsive to consumer needs, and as a surrogate for service quality.4,5

The ‘after hours GP helpline’ (AGPH) was established by healthdirect in 2011 as an adjunct to existing nurse telephone triage and advice services (TTAS) in each state and territory. A key objective of the service was to improve consumer access to after-hours general practitioner (GP) advice for urgent needs, regardless of location or time.6 Similar services have been established around the world to help manage demand for health services, and provide access to health information and advice.7,8

When the AGPH was first established in 2011, callers with an urgent health need in the after-hours period (6.00 pm to 8.00 am on a weekday, 1.00 pm Saturday to 8.00 am Monday morning, and on public holidays) could call a free 1300 number, which connected with nurse triage lines in each state and territory. If assessed by the nurse as needing to see a doctor immediately, or within 24 hours, the caller could speak to a GP on the line for further assessment and advice. Since September 2015, following nurse triage, a GP call-back is available to callers outside major Australian cities in all after-hours periods and residents of major cities in the unsociable after-hours period of 11.00 pm to 7.00 am. The service is funded by the federal government, commissioned by healthdirect, and operated by a third-party provider.

Patient satisfaction with TTAS has been examined in many countries and has generally been found to be high.9–12 Patient satisfaction or experience is a complex construct13,14 that may be influenced by objective factors such as:15–18

- waiting times

- ease of access to the telephone service

- availability of face-to-face services

- less tangible factors such as communication skills of the telephone triagist and clinician

- consumer confidence in the clinician.

Age and ethnicity of patients have also been found to be associated with the level of satisfaction with telephone triage.19 Given the multidimensional nature of patient satisfaction, it is not surprising that measurement of patients’ experience of teletriage services has been found to be methodologically limited13,20,21 and subject to multiple sources of bias.9,22 Consumer satisfaction measures that capture a range of experiential domains are recommended in a recent systematic review.13

An evaluation of the AGPH in 2011–13 (Centre for Health Policy, 2013 unpublished) investigated many aspects of service performance and use. A profile of service users has been described previously in this journal.23 The study reported here examined consumer experience of the AGPH and provides insights into population awareness, caller motivation and perceived benefits of the service. A model is proposed linking user motivation and experience, which may help to target the service to those most in need and enhance its contribution to consumer health literacy.

Methods

A mixed-methods descriptive study design was employed using quantitative and qualitative approaches in an effort to capture the multidimensionality of patient experience. Secondary quantitative data measuring population awareness of the service and caller satisfaction were triangulated with qualitative data from in-depth interviews with service users. The study received ethics approval from the University of Melbourne’s Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 1339934.1).

Three data sources were used. The first was de-identified secondary data from a 2013 national online and telephone survey of 2020 members of the public drawn from every state and territory, aimed at gauging awareness of telephone helplines. The sample was randomly selected and weighted for gender and population distribution according to the 2011 census results (amr, 2013, unpublished).

The second source was a set of de-identified quarterly reports (December 2011 to December 2012) on monthly satisfaction surveys of 200 AGPH users over a 12-month period (n = 600 per quarter), who were selected from callers who had previously agreed to be contacted for evaluation purposes at a later date (Ultrafeedback, 2011, 2012, unpublished). Details of AGPH users in Victoria and Queensland were held by state-based nurse triage services, and callers from these states were not included in the surveys. The demographic characteristics for each sample were included in each report; however, the satisfaction results were reported for the full sample. The secondary data sources were compiled by private market research agencies and were made available to the evaluator by healthdirect.

The third data source was a series of in-depth interviews undertaken with 15 callers to the AGPH. These callers were selected from those who had previously agreed to be contacted for evaluation purposes at a later date. This sub-study was designed and managed by the author; interviews undertaken by a staff member of the same private agency engaged to undertake satisfaction surveys. Full digital recordings of each interview were supplied to the author. Respondents were selected from New South Wales, Western Australia, South Australia and Australian Capital Territory. As noted above, the contact details for AGPH users in Victoria and Queensland were held by state‑based nurse triage services and were not available for this study. Users from the Northern Territory and Tasmania (representing only 1% and <1% respectively of service use)23 were not sampled. A stratified sampling frame was used to reflect the age, gender and caller/patient profile of service users of the AGPH. The results were:

- 60% female and 40% male

- 33% of calls were for themselves, aged 21–49 years

- 26% of calls were for themselves, aged 50 years and older

- 25% of calls were a parent on behalf of a child aged 0–4 years

- 16% of calls were a parent on behalf of a child aged 5 years and older.

Repeat and new users of the service were interviewed. Rurality was not included in the sampling frame. Respondents were asked 16 open-ended questions about their experience of using the helpline, including:

- how the call had influenced being able to deal with the health concern

- their subsequent health service use

- how the respondent felt after speaking with the telephone GP

- how the respondent felt about dealing with a similar problem again

- how the telephone consultation compared with a face-to-face consultation

- what value, if any, the service provides to the community.

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively for frequencies and proportions. Qualitative findings were thematically analysed using the four-step model of Green et al based on immersion, coding, categories and generation of themes, with theme identification moving beyond the data to seek a conceptual understanding of the findings.24

Results

Awareness of the AGPH

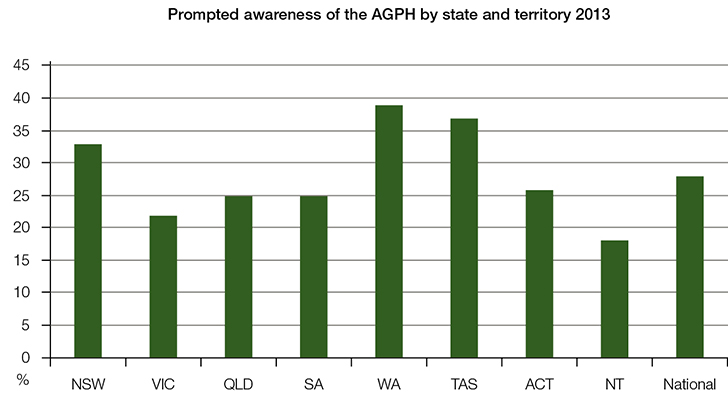

These results relate to the national survey of consumer awareness. Nationally, 28% of the respondents were aware of the AGPH when prompted with a list of telephone services providing health advice. There was little unprompted mention of the AGPH; <1% mentioned it as a telephone service for advice and support, and 2% identified calling the service as an action to take when a doctor is not immediately available. More women (29%) than men (27%) were aware of the service. Prompted awareness of the service was lowest in the 40–59 age group, and in Victoria and Northern Territory. Awareness was highest in the >60 years age group and in Western Australia. Prompted awareness of the AGPH by state and territory is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Prompted awareness of the AGPH by state and territory in 2013 (n = 2020)

(Source: amr research report to healthdirect, April 2013) |

Satisfaction of users

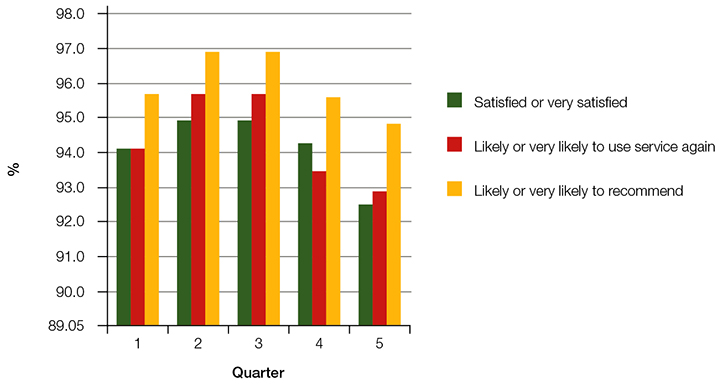

These results relate to quarterly surveys of users of the AGPH. Over a 12-month period, more than 92% of consumers consistently regarded the service highly across three indicators of patient experience:

- satisfaction

- likelihood of using the service again

- willingness to recommend the service to a friend or family member.

A slight reduction in proportions satisfied was apparent in the second half of 2012 as shown in Figure 2. However, for four of the five quarters, 94–94.9% of callers were satisfied or very satisfied with the service.

|

Figure 2. Consumer satisfaction with the AGPH by quarter, December Q 2011 – December Q 2012

(n = 600 per quarter) |

Caller perceptions of value

These results relate to the in-depth user interviews. The characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. All respondents assessed the service as being of great value and identified a range of benefits in relation to their sense of wellbeing and understanding of their health, in addition to advice received about management of the condition that had prompted their call.

Table 1. Characteristics of the AGPH caller interviewees

|

| Caller category | Female | Male | Total |

|---|

| |

First-time caller |

Repeat caller |

First-time caller |

Repeat caller |

|

| Parents calling on behalf of a child aged <5 years |

1 – NSW

1 – WA |

1 – NSW |

1 – NSW |

|

4 |

| Parents calling on behalf of a child aged ≥5 years |

|

1 – NSW |

1 – NSW |

|

2 |

| Callers about self, aged 18–49 years |

1 – WA

1 – ACT |

1 – NSW |

1 – NSW

1 – SA |

|

5 |

| Callers about self, aged ≥50 years |

1 – NSW

1 – WA |

|

1 – NSW |

1 – WA |

4 |

| Total |

6 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

15 |

Emotional benefits

The peace of mind provided by a telephone conversation with a doctor after hours was identified as a significant benefit. Parents of small children, in particular, frequently spoke of the reassurance they felt in having their uncertainty resolved, knowing what to do next or receiving confirmation that they were doing the right thing in responding to their child’s health problem. Having this reassurance in the unsociable after hours was especially valued.

It was so reassuring to find out what to do next and that I was doing the right thing … especially in the middle of the night. – R1, New South Wales, female, parent of a child 5–9 years of age, first-time caller

The advice helped tremendously. It put our mind at ease, which is exactly what you want as a new parent. – R10, New South Wales, female, parent of a child <5 years of age, repeat caller

Relief at knowing what to do next or that the caller was not in danger was a frequently expressed emotion.

I stopped panicking. I was relieved and I felt much more relaxed knowing that I could call them back … it helps people on their own who are worried. – R5, New South Wales, female, >50 years of age, first-time caller

Respondents spoke of the call dealing with their fear in relation to their own health condition or that of their child. Fear was exacerbated by being at home alone when unwell and speaking to a GP on the telephone helped to overcome feelings of isolation and helplessness.

I didn’t have the capacity to go, I couldn’t get out of bed and so I called them and I didn’t feel so alone any more. – R3, Australian Capital Territory, female, 21–49 years of age, first-time caller

I got into bed and the ceiling just looked like it was rotating around … I didn’t know what to do or where to go. So I talked to the nurse and the doctor. – R4, Western Australia, male, >50 years of age, repeat caller

Increased confidence in dealing with the health issue was identified as a benefit by almost all respondents.

In a similar situation I would probably be able to manage it a bit better myself based on the advice of the GP. – R13, New South Wales, male, 21–49 years of age, first-time caller

Increased understanding of the problem and learning about appropriate response strategies should it occur again was particularly highlighted by parents of young children.

I wasn’t sure what I should be looking out for and it gave me some good tools after talking to the doctor. – R8, Western Australia, female, parent of a child <5 years of age, first-time caller

Now that I know I always keep the medicine [for a child with croup] in the cupboard. I know what I need. – R15, New South Wales, female, parent of a child <5 years of age, first-time caller

Impact on use of other healthcare services

Speaking to the GP on the telephone also influenced respondents’ use of other after-hours services. Avoiding attendance at hospital or the emergency department (ED) was identified as a reason to call and an outcome of the call for some. The convenience of not needing to travel and time saved for the caller and the ED were greatly valued by respondents.

I wanted to avoid that [ED] at all costs. To take a baby to an environment ... where people are highly stressed or upset or ill – I was happy to avoid going there. – R8, Western Australia, female, parent of a child <5 years of age, first-time caller

I didn’t want to go to ED if I didn’t have to. You might be wasting their time [ED] when someone else could be taking that time. – R12, South Australia, male, 21–49 years of age, first-time caller

For those who were assessed as needing healthcare soon, callers were grateful that they could take that action with confidence because they had received advice that it was necessary.

I could take the advice easily. I made the decision to go. – R15, New South Wales, female, parent of a child <5 years of age, first-time caller

Others commented on the value of knowing it was all right to wait until the next day to see a GP.

It has saved us two trips to the hospital really. – R10, New South Wales, female, parent of a child <5 years age, repeat caller

Comparison of telephone experience with face-to-face after-hours care

While most respondents acknowledged that face-to-face care was essential for full diagnosis and treatment of a condition, the capacity to get advice almost immediately when uncertain or during unsocial hours was seen as very valuable.

I don’t know if the doctor can actually fix you over the phone … advice is helpful but it can’t fix you. – R9, New South Wales, male >50 years of age, first-time caller

Although not viewed as a replacement for one’s own doctor, the AGPH was seen as a preferred alternative to attending a hospital in the after-hours period and for others, the only medical care accessible at that time.

It was a necessity because GPs aren’t open 24 hours and the hospital is 45 minutes away. – R6, New South Wales, male, parent of a child <5 years of age, first-time caller

Discussion

Population-level awareness of the AGPH was very low, with even prompted awareness of the service representing less than one-third of the sample. Limited awareness most probably reflects the contained approach taken to marketing the service via posters, magnets and keyrings distributed through health services, and very limited mass media promotion. Low awareness in Victoria may reflect strong brand awareness of the Victorian Nurse-On-Call service, which has been in operation since 2007 and to which the AGPH has been appended. Patient satisfaction with similar services elsewhere in the world is generally rated positively,10,11 and users of the Australian AGPH are no different in this regard, with survey results consistently demonstrating high caller satisfaction.

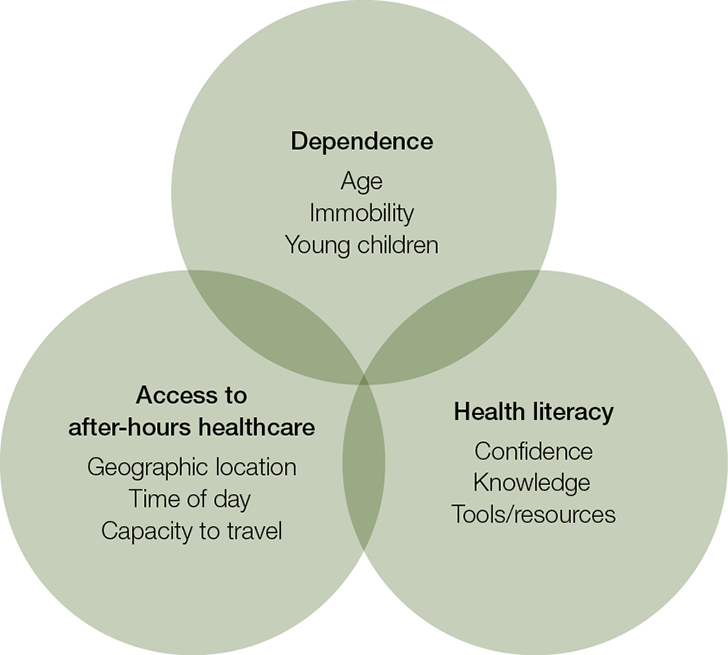

A deeper exploration shows that consumers of GP telephone advice in the after hours use the service with varying motivations and derive a range of perceived benefits. Consumers call the service because they are uncertain and lack knowledge of the condition affecting them. They are often in a dependent or vulnerable state in the after-hours period because of older age, isolation, immobility resulting from their condition or the presence of small children. Their access to primary care services and/or hospital services at that time may be limited because of geographic location, time of day or their inability to independently travel to a service. Callers experience reassurance, peace of mind and help with decision-making, which translates to a state of greater confidence. They gain strategies to deal with the health condition and feel better equipped to deal with the problem should it arise again. Each of these latter elements is an important aspect of health literacy, which in turn is linked to physical health outcomes and the way in which consumers manage their health and use health services.25

A conceptual model can be constructed that captures reasons for using the service and perceived immediate value for consumers. Such a model may guide targeting of the service to those who will derive the greatest benefit. Figure 3 presents the interrelated experiential domains of dependence, access and health literacy to illustrate the relationship between motivation for using the service and perceived benefits. Changes to AGPH availability from September 2015 are in part consistent with the more targeted approach that this conceptual model suggests. Evaluation of the service in its amended form will provide evidence as to the utility of the model.

|

| Figure 3. Conceptual model of the interrelated motivations and perceived benefits of using the AGPH |

Limitations

The results in the awareness and satisfaction surveys were not presented by rural and urban location. Reasons for dissatisfaction were not available. The qualitative component was based on a limited sample of 15 users of the helpline and may not be generalisable to all users. Respondents were drawn from only three states and the Australian Capital Territory, and rurality was not specified in sampling. The conceptual model derived from thematic analysis requires consultation and testing. Nonetheless, the stratified sampling frame was representative of the user profile in terms of age, gender and caller/patient status, and there was a high degree of concordance in relation to reasons for using the service and the immediate benefits derived, supporting the plausibility of the model.

Conclusion

While user satisfaction with the AGPH was high, population awareness of the service was low. In-depth analysis of user motivation and perceived benefits reveals three key interrelated experiential domains. A conceptual model based on dependence factors, access to after-hours services and health literacy would suggest that the service could be targeted to population groups such as the elderly, parents of young children and those with limited access to after-hours services, such as rural populations. The service may contribute to improved health literacy in users but this domain and the model overall require further research.

Implications for general practice

- After-hours GP telephone advice is valued by consumers and may be a useful addition to face-to-face general practice services by providing reassurance, guidance on whether face-to-face care is needed and confidence in managing conditions.

- With wider public awareness the service could support community-based general practice in meeting patient needs in the after hours, especially for patients who are geographically or socially isolated, have limited mobility or limited capacity to access after-hours services.

Author

Rosemary McKenzie BA, PGDipHP, MPH, Director of Teaching and Learning, Deputy Director Centre for Health Policy, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Carlton, Vic. r.mckenzie@unimelb.edu.au

Competing interests: Rosemary McKenzie’s institution was contracted and paid by healthdirect to evaluate the ‘after hours GP helpline’ and received travel support from the organisation. She has also led three evaluation-related projects for healthdirect.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

Professor David Dunt jointly led with Rosemary McKenzie the evaluation of the AGPH, of which this study was a component. Michelle Williamson and Allison Yates were project officers on the evaluation. Sharon Blair interviewed consumers.