Benzodiazepines are a widely prescribed class of medication, estimated to be used by 15.7% of the Australian population older than 65 years of age.1 They are indicated for short-term management of anxiety and insomnia; however, chronic use frequently occurs. Nocturnal benzodiazepine use can have significant adverse effects, particularly in the elderly, including an increased risk of falls, fractures, road traffic accidents and cognitive decline,2–4 as well as associated socioeconomic costs.5 Studies have found that benzodiazepines provide limited benefit when used for longer than two to four weeks.6 In addition to the economic benefits of reducing the use of an ineffective and potentially harmful treatment, studies have found cognitive improvement in elderly patients who stopped using benzodiazepines,7 and no effect on their long-term sleep patterns.8 Significantly limiting their use, or withdrawing the medication from chronic users, is therefore important.

Although most general practitioners (GPs) are aware of the health and addiction risks of benzodiazepines, this class of medication continues to be initiated and sustained through repeat prescriptions. It has been suggested that GPs perceive potential difficulty with discussing the cessation of nocturnal benzodiazepines because of:

- anticipated resistance from the patient and ensuing conflict9

- pessimism about the success of taper withdrawal techniques10

- viewing it as an unrewarding process.11

In addition, GPs often underestimate their role in a patient’s decision-making process.12 GPs feel that they have a lack of knowledge and are under-resourced to provide alternative strategies.10 A study by Anthierens et al13 reported that only one-third of GPs surveyed felt their knowledge of non-pharmacological therapies was sufficient. The study concluded that approximately 50% of GPs surveyed thought the patients expected a prescription and 18% thought not writing a script would threaten the doctor–patient relationship.

Existing studies on nocturnal benzodiazepine use have primarily looked at the chemical addiction,7 mechanisms of withdrawal,14,15 patient characteristics16 and attitudes of GPs prescribing them.17,18 Studies in Australia reflect the general literature targeting prescribing trends,19,20 prevalence of use,1,21 characteristics of users16 and patterns of use.22 There are some international data suggesting that long-term users of benzodiazepines may be willing to cease use,8,23 but this has not been investigated in the Australian population. One Australian study investigated the views of GPs and benzodiazepine users regarding the medication use, but the attitudes to stopping was not discussed.11 Furthermore, this study included participants of all age groups and not specifically the elderly, in whom adverse effects are arguably more problematic.

To provide further data to assist GPs and patients in reducing chronic nocturnal benzodiazepine use, this study aimed to more fully investigate patients’ attitudes to cessation and whether resistance exists in the elderly Australian patient population.

Methods

A qualitative study design using semi-structured interviews was employed to assess elderly patients’ use and knowledge of nocturnal benzodiazepines, and their attitudes to cessation. This study was conducted between November 2013 and July 2014.

Recruitment

A convenience sample of four general practices from the Illawarra and Southern Practice Research Network were recruited. These were large general practices with 9−22 doctors. Three of the practices were classified as Category 1 on the Australian Standard Geographical Classification – Remoteness Areas (ASGC-RA) and the remaining practice classified as Category 3.

The participating practices’ electronic medical record databases were screened to identify patients who met the inclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Individual GPs screened the list further to confirm potentially suitable patients. The first 10–12 patients on the list were then invited by mail to participate in the study.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

|

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|

| Patients older than the age of 65 years |

Nursing home and hostel patients |

| Two or more prescriptions for nocturnal benzodiazepines in the past six months |

Patients whom GP considers cessation of benzodiazepines could have a detrimental effect on health |

| |

Patients whom GP considers are not able to give informed consent |

| |

Patients unable to speak English |

| |

Patients known to be in distress from any cause |

Interview and analysis

The semi-structured interview guide, used as part of the telephone interviews with consenting study participants, was developed from themes arising from the literature review and personal reflections by the GP researchers. Sample questions included:

- I am interested in understanding how you first started using your sleeping tablets – can you recall how that came about?

- What do you think your doctor’s attitude is to you taking this medication?

- Can you tell me your thoughts on stopping the medication?

- When you started taking the sleeping tablet, how long did you expect to be taking it?

- Are you aware of alternative treatment options for insomnia?

The transcripts of the audio-recorded telephone interviews were independently analysed using a constant comparative analysis framework by the lead and first researcher, and key themes were identified. The results were disseminated to the research group for review and comment.

Ethics

This research study was formally approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the University of Wollongong (HREC approval number HE13/013).

Results

A response rate of 40% was achieved. In total, 17 telephone interviews were completed, digitally audio-recorded and included in the analysis, although the researchers’ felt no new themes were identified after the 15th interview. The average length of each interview was 15 minutes. Of the 17 participants, 13 were women and four were men, with an average age of 77 years and 73 years respectively. The majority of patients had been taking benzodiazepines nocturnally for a considerable time (Table 2).

The frequency of use varied between participants, with some taking benzodiazepines on a nightly basis and some only on occasion. Infrequent use was often cited by patients as justification for ongoing use.

Table 2. Duration of use

|

| Length of time taken | Number of patients |

|---|

| 1–5 years |

5 |

| 6–10 years |

4 |

| 11–15 years |

3 |

| 16–20 years |

2 |

| Longer than 20 years |

1 |

| Unable to recall |

2 |

Key themes identified from the transcripts

Three key themes were identified from the transcripts and will be discussed in further detail:

- commencement and continuation of nocturnal benzodiazepines

- patients’ knowledge of benzodiazepines and alternative options

- patients’ attitudes to benzodiazepine use and cessation.

The first main theme identified was commencement and continuation of nocturnal benzodiazepines. Study participants had often commenced nocturnal benzodiazepines at a time of personal stress.

I was having a few problems with one of our neighbours and I wasn’t sleeping at all. – Female, 72 years of age

My husband got killed in a car accident and I had three little children; one was only 2 weeks old. – Female, 73 years of age

For many of the participants, a confounding factor such as pain or nocturia was the current cause of sleep disturbance. This was largely unrelated to the reported cause of insomnia at the time of benzodiazepine initiation.

I’m waiting for a hip replacement. When I get in to bed it starts to ache. – Female, 77 years of age

Mainly I wake up because I have to go to the bathroom. – Female, 86 years of age

Despite chronic use of these medications by the study participants, most of them had not considered how long they would be taking them.

Well I was hoping not forever. – Female, 72 years of age

No expectations at all. I just took them. – Male, 68 years of age

Many of the participants perceived limited benefit from taking nocturnal benzodiazepines, yet they continued to use them.

Not much use, fall asleep for 1 hour then find it hard to get back to sleep again. – Female, 73 years of age

I don’t get a full night’s sleep with them. – Female, 86 years of age

The reasons for ongoing nocturnal use of benzodiazepines despite limited reported benefits revealed that a goodnight’s sleep was important to participants’ health and many participants feared they would not sleep at all if they did not take them.

Well if I don’t take them, I literally don’t get any sleep. – Female, 86 years

Some had come to rely on nocturnal use of benzodiazepines as a safety net. Others felt that if they were not experiencing side effects and they were not harmful, it was acceptable to continue with benzodiazepines.

Well there’s no reason why I couldn’t stop them, as I say it’s just the fact that they’re there but I know that they’re not real strong tablets. They’re not going to hurt me. – Female, 77 years of age

If it’s not doing any damage to my health, why should I go off it? – Female, 81 years of age

Many participants had previously tried to stop taking nocturnal benzodiazepines, although this was often impromptu and without any support from their GP. In many instances, patients found they could not sleep and restarted the drug again.

Well a couple of times I wouldn’t take one and I laid awake for hours and hours and ended up getting up and taking one. – Female, 73 years of age

I’ve tried several times but normally it’s only been one night. I’ve even tried sort of cutting them down. In fact I tried that for about a week I think and it didn’t work. – Female, 86 years of age

I went for about four nights, but I was still waking up so I thought blow it. I’m over this. – Female, 77 years of age

The second major theme identified from the interview transcripts related to the participants’ knowledge of benzodiazepines and alternative options available. The study identified that many of the patients were unaware of potential side effects apart from sedation.

No effect on me because they are weak ones. – Female, 77 years of age

Just what’s marked on the packet – ‘may cause drowsiness’. – Female, 86 years of age

A variable lack of insight existed around the addictive nature of benzodiazepines.

Well I think so although they say that temaze aren’t. – Male, 79 years of age

I suppose they are – if you’ve got them you’re going to take them aren’t you. – Female, 77 years of age

No, if you are good in your head you can control it. – Female, 68 years of age

Study participants in the majority of cases were unaware of alternative treatments available for insomnia.

No not that I am aware of. – Female, 73 years of age

Probably get hypnotised I suppose. No I don’t really know of anything. – Female, 79 years of age

Only one patient recalled having alternative options discussed with them at the time of benzodiazepine initiation.

I had from the health shop different concoctions. I tried them but never ever made a difference at all. – Male, 67 years of age

The third and final major theme identified in the transcripts included attitudes to benzodiazepine use and cessation. The majority of study participants attended the same GP for repeat prescriptions and felt that their GP approved of sleeping tablet use.

He was quite happy for me to take it. – Male, 90 years of age

Well she doesn’t say anything. It didn’t worry her she just wrote the script. – Female, 73 years of age

Well I moved here and I just asked for a script for them and they haven’t asked any reason why I take them or anything. No they’ve just given me the script. – Female, 86 years of age

Many of the patients expressed a willing attitude to cessation of sleeping medications, suggesting that patient resistance may not exist.

I would dearly like to stop it. I wish I didn’t have to take them. – Female, 86 years of age

Well I’d like to try. – Female, 73 years of age

If the doctor said to me I don’t want you to take it anymore … I wouldn’t take them. – Male, 67 years of age

Discussion

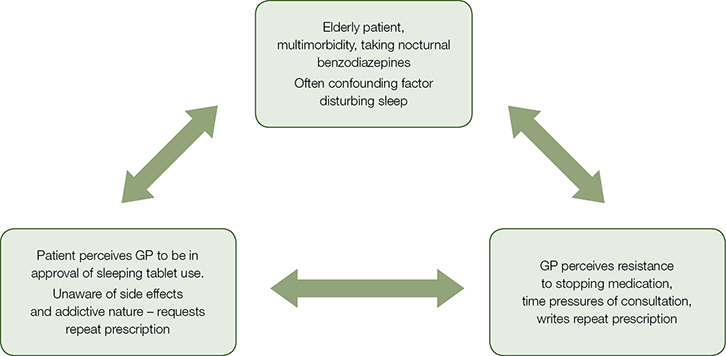

The continued nocturnal use of benzodiazepines by the elderly is a complex problem. The Therapeutic Goods Administration’s (TGA’s) indication for the nocturnal use of benzodiazepines is for the short-term treatment of insomnia.19 However, many of the patients in this study had been taking the medication for a considerable length of time, despite limited benefit. The medication was often initiated at a time of stress and was continued indefinitely. The majority of patients showed a willingness to cease the medication, but did not see a need to cease, as they were not aware of the potential side effects or addictive nature of benzodiazepines. Continued use was facilitated by patients perceiving that their GP approved of their use, fear of not sleeping, past experience of stopping, and rating a good sleep as important to health. A circle of silence appears to exist around nocturnal benzodiazepine use by the elderly (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Circle of silence |

GPs may be reluctant to challenge the patient because of perceived resistance and possibly time constraints in consultations with elderly patients, who often have multiple comorbid conditions to manage.24 The patient may not be aware of any problems with taking the medication and, hence, may not discuss the possibility of stopping, so, the cycle of use continues.

Patients often feared insomnia, with some having experienced it on previous attempts at briefly stopping. These cessation attempts were generally done ad hoc with no support from the GP. Various strategies have been shown to be successful in facilitating cessation.9,25,26 A study by Cormack et al revealed that older people are just as good, if not better, at reducing the consumption of benzodiazepines as younger people.27 Discussions regarding cessation should involve education about rebound insomnia28 and investigation into the cause of sleep disturbance. Many patients in the study had confounding factors contributing to sleep disturbance, which could be better managed with targeted therapies.

This conceptualisation of continued, unnecessary benzodiazepine use has support in the literature. Previous research in the UK by Morrice and Iliffe,29 and in Canada by Cook et al,23 highlighted that GPs often under-estimate the willingness of long-term benzodiazepine users to attempt withdrawal, and that the majority of physicians believed that attempting withdrawal would be time-consuming and futile.23

To date, one Australian study has looked at the views of users and GPs on benzodiazepine use and found a similar physician belief regarding the difficulty of counselling patients on cessation, with this being viewed as unrewarding.11 Patients in that study expressed concerns that GPs did not raise the issue of ceasing use.

A study by Cook et al suggests that physicians often underestimate their own influence on a patient’s decision to cease or continue benzodiazepines.23 Our study highlights that willingness to withdraw may exist. In addition, not challenging a patient may also influence a patient’s decision to continue benzodiazepines, with a lack of challenge being taken as approval.

This study concurs with current literature suggesting that insomnia in the elderly is often poorly managed in general practice. The use of more suitable therapies other than nocturnal benzodiazpines are often overlooked30 and proven therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy for isolated insomnia are underused.31,32 Silvertsen et al found that hypnotics were still considered to be the most successful treatment option by many GPs.33

Limitations

The findings of this research are limited to some extent by the small number of participants. Although a reasonable response rate was obtained, it is possible that only those patients who were potentially motivated to stop the medication replied and that non-responders were not interested in cessation. In addition, a convenience sample from four general practices was used, which may not truly be reflective of Australian general practice as a whole. There may also be reporting bias from the interviewees, who may have been inclined to give answers that they expected the interviewer wanted to hear. Furthermore, the sample group is skewed towards women, with 13 women and four men. This age group in general has a higher proportion of women to men, given the differences in longevity between the sexes. Women also have a higher prevalence of benzodiazepine use.16

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for ongoing medication review in patients who are elderly. Nocturnal benzodiazepine use in the study group may well have been justified initially, but may have continued without evidence of ongoing need or benefit. The cause of sleep disturbance at the time of interview was, in many cases, a confounding health issue, with alternative treatment options available. Patients’ lack of knowledge of nocturnal benzodiazepines’ side effects and addictive potential compounds their ongoing use. While this may reflect poor recall or explanation at the time of initiation, it highlights the need for better communication and patient education surrounding medication use.

As shown in this study, many patients may be willing to cease long-term nocturnal benzodiazepine use and the anticipated resistance may not exist. GPs should be encouraged by this knowledge to spend time with patients presenting for repeat prescriptions of nocturnal benzodiazepines, discussing the cause of sleep disturbance, potential side effects of the medication, availability of alternative options and exploring the need for ongoing use. This may reduce the use of this potentially harmful medication in patients who are elderly.

Implications for general practice

- Nocturnal benzodiazepines are not indicated for the long-term treatment of insomnia.

- A thorough sleep history should be carried out for any patient presenting with insomnia.

- Confounding factors are often the cause of sleep disturbance and more targeted treatments may be available.

- Patients presenting for repeat prescriptions of benzodiazepines should have their medication reviewed to discuss side effects, addictive potential, alternative options and need for ongoing use.

- Many patients may be willing to cease the medication and may not be resistant to change.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ms Alyssa Horgan for her research administration and assistance during the project, to Dr Judy Mullan for her helpful review of the manuscript, and to the four participating practices and staff. This project was funded and supported by a Coast City Country General Practice Training grant.

Authors

Fiona Williams MbChB, MRCGP, FRACGP, DRCOG, GradCert MedEd, Regional Academic Leader and Clinical Senior Lecturer, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, and General Practitioner, Thirroul, NSW. fionaw@uow.edu.au

Carl Mahfouz MBBS, FRACGP, Regional Academic Leader and Clinical Senior Lecturer, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, and General Practitioner, Shellharbour, NSW

Andrew Bonney MBBS, MFM (Clin), PhD, FRACGP, Roberta Williams Chair of General Practice, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, NSW

Russell Pearson MBBS, FRACGP, FACRRM, GradCert Health Research, Regional Academic Leader and Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, and General Practitioner, Gerringong, NSW

Bastian Seidel MBBS, PhD, MRCGP, FRACGP, Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, NSW, and General Practitioner, Huon Valley, Tas

Bridget Dijkmans-Hadley BA (Population Health), MMSc (Res), Project Coordinator, Illawarra and Southern Practice Research Network (ISPRN), Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, NSW

Rowena Ivers MBBS, PhD, MPH, FRACGP, Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, and General Practitioner, Wollongong, NSW

Competing interests: None

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.