Case

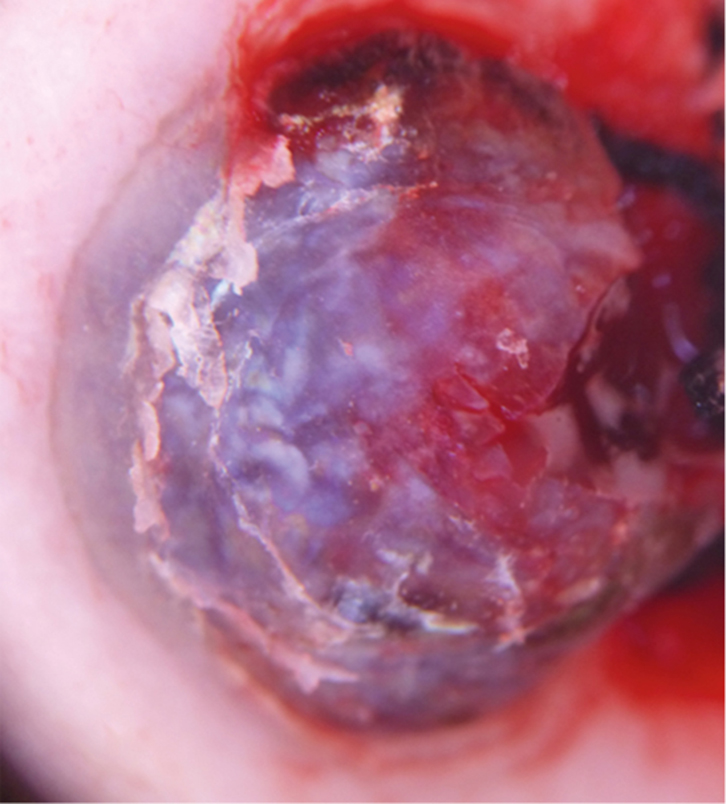

A man, 84 years of age, presented to the dermatology clinic with a progressively growing and occasionally bleeding lesion on the sole of his left foot. Of note, there was no history of trauma and he was otherwise healthy. The patient did not remember when the lesion first appeared and was only aware of the lesion when it began to bleed approximately two months before the consultation. On examination, a purplish nodule with clear-cut borders and central ulceration was seen (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Clinical presentation: violaceous nodule with precise borders on the sole of the left foot, with a centrally friable and ulcerated area |

Question 1

What main differential diagnoses should be considered?

Question 2

What further clinical history is important to consider?

Question 3

Which other examinations and/or investigations should be carried out?

Answer 1

Differential diagnoses are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses of nodular bleeding lesions in an elderly man,

with dermatoscopic descriptions

|

| Condition | Features | Dermatoscopy |

|---|

| Pyogenic granuloma |

- Benign vascular neoplasm

- Rapidly growing, friable red papule of skin or mucosa that frequently ulcerates

- Most common in children and young adults

- Unknown aetiology

|

- Reddish homogeneous area, white collarette, ‘white rail’ lines and ulceration1

|

| Amelanotic melanoma |

- Non-pigmented variant of melanoma

- Growing papule or nodule

|

- Non-specific

- Atypical vessels

|

| Angiosarcoma |

- Rare, malignant vascular tumour

- Can occur on face and scalp of elderly patients

- Areas of chronic lymphedema or radiodermatitis

- Rapid growth

|

- Milky-red to brownish-red areas without distinct borders, individual lagoons (lacunae), polymorphous vessels and blood-filled fissures

|

| Classic Kaposi sarcoma |

- Disease of patients older than 50 years

- Slow growing pink-violet macule, then plaque or nodule

- Distal lower extremities

|

- Bluish-reddish colouration

- Rainbow-coloured area

- Scaly surface2

|

| Basal cell carcinoma |

- Shiny papule or plaque ulcerated

- Very slow growing

|

- Arborising telangiectasias

- Maple leaf–like areas

|

| Merkel cell carcinoma |

- Firm, painless nodule, flesh coloured, red or blue

- Most frequent on sun-exposed areas

- Locally aggressive with high metastatic potential

|

- Polymorphous and poorly focused vessels among milky pink and white areas

- Structural disorder3

|

Answer 2

It is important to determine if the patient has any melanoma risk factors, and to confirm that he is not on any immunosuppressive medication. These medications may modify the epidemiology and clinical presentation of cutaneous tumours.

Answer 3

It is mandatory to explore the whole skin surface to look for other lesions. Dermatoscopy would help in the consideration of a vascular, keratinocytic or melanocytic origin. A biopsy should be performed for histopathological study.

Case continued

This patient lived in the north of Spain, where daily sun exposure is limited, but he spent each summer further south on the Mediterranean, so intermittent sun exposure was presumably high. He had no personal or family history of melanoma. His skin was phototype III (fair to medium tan skin tone, which burns sometimes and tans gradually),4 with few naevi, none of which was atypical, consistent with low-risk melanoma. However, this finding does not exclude melanoma as a possible diagnosis, especially in non–sun-exposed sites such as the soles. The patient denied taking any immunosuppresive medication. On dermatoscopy (Figure 2) the lesion had sharp, keratinised borders showing red, blue and white areas in the centre. These findings are a clue to vascular origin. The presence of ‘rainbow areas’ points to Kaposi sarcoma but is non-specific so amelanotic melanoma cannot be ruled out on the basis of this alone. Histological examination of the biopsy found proliferation of fusiform cells within the dermis, which is associated with inflammatory infiltrate and many vessels. The patient’s cells stained positive for human herpesvirus 8, but was negative for melan A (a melanoma-specific marker).5

|

| Figure 2. Dermoscopic image of the lesion: papular red-blue lesion with white and ‘rainbow pattern’ areas and squamous areas |

Question 4

What is your diagnosis?

Question 5

What is the preferred therapeutic approach?

Answer 4

The diagnosis is classic Kaposi sarcoma at the nodular stage. Cellular staining with human herpesvirus 8 is very specific, and this virus is a known cause of this neoplasm.

Answer 5

As the lesion was solitary, a surgical approach without the need for large surgical margins is reasonable. If it had been larger or multifocal, radiotherapy would have been a possibility.

Discussion

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplastic disease caused by human herpesvirus 8 infection. Four variants of Kaposi sarcoma have been described, which present with similar cutaneous lesions that vary depending on clinical variant – pink patches to violet plaques in early stages, to nodules or tumoural polyps in later stages.6 Lesions can be solitary or multiple.

The four variants differ mainly on the epidemiological aspects and are: African endemic Kaposi sarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma associated with iatrogenic immunosuppression, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related epidemic Kaposi sarcoma, and classic Kaposi sarcoma, which appears in patients typically after the fifth decade and mainly in males of Mediterranean or Eastern European origin. Classic Kaposi sarcoma presents as slow-growing, red-violet macules on the distal lower extremities that can coalesce to form large plaques, develop into nodules, or even regress spontaneously. Sometimes, nodules are the first clinical observation since macules and plaques are asymptomatic.

Kaposi sarcoma is considered a borderline, low-grade malignant neoplasm that may have different outcomes, depending on the patient’s comorbidities. It is especially aggressive when associated with AIDS, as many lesions appear simultaneously, affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract and other viscera. African endemic Kaposi sarcoma has a lymphadenopathic subtype that affects children and has a fatal outcome. When Kaposi sarcoma is associated with iatrogenic immunosuppression, complete resolution may be achieved on cessation of the immunosuppressive therapy.

In classic Kaposi sarcoma, which mainly affects immunocompetent patients and typically has a chronic and protracted course, achieving a complete cure might be unrealistic given the frequency of recurrence.7 For the treatment of solitary lesions, surgical approach or radiotherapy are the preferred options. When multiple lesions are encountered, observation and close follow-up might be an option. Only rapidly progressive (more than 10 or more new cutaneous lesions in a month) or symptomatic visceral involvement require systemic chemotherapy.8

Key points

- Kaposi sarcoma is a cutaneous neoplasm that should be considered mainly in patients older than 50 years of age, or in patients who are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive when a papule, nodule or plaque with red or violaceous hue is seen.

- Dermatoscopy of Kaposi sarcoma is non-specific, but a rainbow pattern is typically observed.

- In all tumoural, non-specific cutaneous lesions, melanoma should always be a main differential diagnosis.

Authors

Claudia Bernárdez MD, Dermatologist, Department of Dermatology, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain. claudiabernardezguerra@gmail.com

Salma Machan MD, Dermatologist, Department of Dermatology, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain

Jose Luis Ramírez-Bellver MD, Dermatologist Trainee, Department of Dermatology, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain

Elena Macías MD, Dermatologist Trainee, Department of Dermatology, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain

Jose Luis Diaz-Recuero MD, Dermatologist and Pathologist, Department of Dermatology, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed