The health of young people is an important indicator of the population’s future health.1 Adolescence is a time of change and a critical period in which a person’s future can be altered. Adolescent health has received greater attention from the World Health Organization (WHO) as there are many preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in this age group. These include motor vehicle accidents, violence, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and suicide.1–7 Lifelong habits, such as tobacco use, poor diet and physical inactivity, develop in adolescence and can have adverse outcomes later in life.2,4

General practice is the specialty best equipped to address the main emphases of adolescent healthcare: preventive health; development of protective factors; and addressing the social determinants of health.2,3 Establishing rapport and a trusted relationship with a general practitioner (GP) during youth is important so that it may continue across the lifespan.5,8 However, there remain some challenges in implementing and maintaining this relationship.1,3,5,7,9,10

Reported barriers to youth accessing healthcare include concerns about confidentiality,1,2,4,7–9,11 being unsure of the GP’s role,1,2,12 poor doctor–patient relationships4,10 and previous bad experiences.1,5,9 Although adolescents’ experiences are varied, the perception of discrimination and stigma by healthcare professionals is a barrier to young people expressing their concerns or revealing their symptoms.1 Poor communication between doctor and patient is also a deterrent.8 Adolescents and GPs may be uncertain of their respective roles. Adolescents also view topics such as mental health negatively and confronting to discuss.1,2,3,6,9

Adolescents are more likely to access healthcare services on the basis of the approachability of all staff at a practice, including reception staff.2,8 Previous studies suggest that in order to improve policy, the perspectives of adolescents on the design and delivery of services need to be championed.4,8 To promote increased access for young people in north-west Tasmania, we sought the perspectives of high school students on what they value when accessing care at a general practice.

Methods

The study included a questionnaire that consisted of 23 questions, with six open-ended questions to capture free-text responses. It was developed to capture simple demographics (eg ethnic background, age, gender) and responses to questions derived from the literature, about barriers and enablers to young people getting care. The questionnaire was piloted with young people, and as a result, responses requiring rating were simplified into three-point Likert rating scales (eg ‘Really helpful’, ‘Somewhat helpful’, ‘Not helpful’).

The study was conducted in a large pre-tertiary school in rural Tasmania.

A local GP and co-author established an onsite GP clinic at the school, which is available to students one morning per week. This established relationship with the school enabled the research team to readily engage with the school’s executive to conduct the study.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Tasmanian Human Research Ethics Committee (reference H15003), the Tasmanian Department of Education and the school.

Students were initially informed of the study at a school assembly and written information was provided. The study information sheet stated the aims of the study, which were to determine how young people today feel about local healthcare services and to collect adolescents’ perspectives on barriers to accessing healthcare. The study information sheet stated that participation in the research was voluntary and decisions not to participate would not affect the students’ or parents’ relationship with the school. The sheet also described that participation in the study would consist of an electronic questionnaire and no personally identifiable information would be collected, to ensure participant anonymity. To be included in the study, participants needed to provide their own written consent, as well as written consent from a parent/guardian if participants were under 18 years of age.

The survey was completed in school time during health classes, using the application ‘iSurvey’ on iPads. The availability of classes for the survey was directed by the school principal in discussion with the health class teachers. Over a four-week period, six classes, with a total of 160 students, were approached. Fourth-year medical students showed the students how to use the iPad and were on hand to assist students if required. The iSurvey automatically recorded survey start and end times. Time taken to complete the survey ranged from two minutes to 10 minutes and 44 seconds, with an average of 5 minutes and 9 seconds.

Survey data were exported from iSurvey into Excel and subsequently imported into Stata14 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) for analysis. Frequencies, means and standard deviations were produced for demographic characteristics and variables related to GP access.

Results

One hundred and fifty-five students completed the survey; five students declined participation. The mean age of the students was 17 years (range 16–19 years), 150 students had an Anglo-Australian background and women comprised 67.7% of the sample (Table 1). Ten students (6.5%) had an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander background. GPs (off campus) were the usual healthcare providers for 147 (94.8%) participants, with eight participants describing the school health clinic (also staffed by GPs) as their usual healthcare provider (Table 1). The most common additional healthcare providers were pharmacists (n = 74; 47.7%) followed by emergency departments (ED; n = 38; 24.5%), online services (n = 32; 20.6%) and the school health clinic (n = 21; 13.5%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and usual healthcare provider of respondents (n = 155)

|

Topics

|

n (%)

|

|---|

|

Gender

|

|

|

Female

|

105 (67.7)

|

|

Male

|

50 (32.3)

|

|

Age, mean years (standard deviation)

|

17 (0.8; range 16–19)

|

|

Usual healthcare provider

|

|

|

GP

|

147 (94.8)

|

|

Other healthcare provider

|

8 (5.2)

|

|

Additional healthcare provider (if more than one provider)

|

|

|

Pharmacy

|

74 (47.7)

|

|

Emergency department

|

38 (24.5)

|

|

Search online for health advice

|

32 (20.6)

|

|

School health clinic

|

21 (13.5)

|

|

headspace

|

5 (3.2)

|

|

Alternative health practitioner

|

3 (1.9)

|

|

Family planning or sexual health clinic

|

2 (1.3)

|

|

Family member

|

2 (1.3)

|

|

Psychologist

|

1 (0.6)

|

While 124 (80.0%) participants reported that it would be ‘Really useful’ to see the same GP at each consultation, only 29 (18.7%) reported seeing the same GP at each consultation. However, an additional 104 (67.1%) respondents reported that they see the same GP ‘Most of the time’. Ninety-five (61.3%) respondents had previously seen a GP without their parent or guardian being present and 132 (85.2%) stated that it would be ‘Helpful’ or ‘Very helpful’ to see a GP without a parent present.

The most commonly reported barriers to young people accessing healthcare were ‘hoping the problem would go away by itself’ (n = 100; 64.5%), difficulties obtaining an appointment at a convenient time (n = 87; 56.1%) and not feeling comfortable seeing a GP (n = 62; 40.0%; (Table 2).

Table 2. Barriers to accessing GP care (n = 155)

|

Barrier

|

n (%)

|

|---|

|

Hoping the problem would go away by itself

|

100 (64.5)

|

|

Difficulty obtaining an appointment at a convenient time

|

87 (56.1)

|

|

Did not feel comfortable going to a GP

|

62 (40.0)

|

|

Felt too embarrassed to go to a GP

|

56 (36.1)

|

|

Confidentiality concerns

|

51 (32.9)

|

|

Could not afford to go to the GP

|

37 (23.9)

|

|

Previous negative experience with a GP

|

26 (16.8)

|

|

Difficulty understanding GP (due to accent)

|

3 (1.9)

|

|

Travel or lack of transport

|

3 (1.9)

|

|

Male GP (would prefer a female GP)

|

2 (1.3)

|

|

GP asking inappropriate questions

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Condescending attitude of GP

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Long waiting time for appointment

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Not knowing how the payment system works

|

1 (0.6)

|

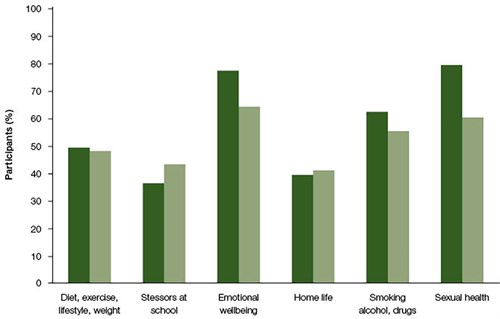

One hundred (64.5%) participants deemed it ‘Really important’ to discuss issues of mental health, drugs and alcohol, and sexual health with a GP, even if they presented for another reason; a further 50 (32.3%) deemed it ‘Somewhat helpful’. Contraception, STIs and pregnancy were the second most important issues (n = 93; 60.0%) for GPs to discuss, even when young people presented for other reasons (Figure 1). One student commented in the free text space that:

It would be good if the GP brought it up because I would be too embarrassed to talk about it if not asked.

Figure 1. Important topics to discuss with a general practitioner

Bars represent the percentage of participants who consider issues ‘really helpful’ to discuss with a general practitioner (dark green ) and issues ‘really helpful’ for a general practitioner to ask about (light green)

Over 90% of participants deemed the following to be ‘Really important’ qualities of a GP:

- listening skills (n = 151; 97.4%)

- easy to talk to (n = 147; 94.8%)

- makes young people feel comfortable (n = 144; 92.9%)

- non-judgmental attitude (n = 143; 92.3%).

The age of the GP was not a concern for 88 (56.8%) participants (Table 3). Comments provided in this section included:

That the doctor does not comment negatively on my lifestyle choices (eg diet, sexuality).

That they respect my problems the same as any adult, and not tell me that ‘you’re just young and paranoid.

Understandable, doesn’t speak too quickly or in a low tone or mumble.

Nearly all (n = 152; 98.1%) participants stated that it would be ‘Somewhat helpful’ or ‘Very helpful’ if reception staff were able to recommend a GP who was ‘youth friendly’. After-school appointments were considered the second most important quality in a GP clinic, with 153 (98.7%) respondents stating that flexible appointment times were either ‘Somewhat important’ or ‘Very important’.

Table 3. Respondent ratings of important GP qualities

|

Important qualities in a GP

|

Not important n (%)

|

Somewhat important n (%)

|

Really important n (%)

|

|---|

|

Listens to young patients

|

4 (2.6)

|

4 (2.6)

|

151 (97.4)

|

|

Is easy to talk to

|

8 (5.2)

|

8 (5.2)

|

147 (94.8)

|

|

Makes young patients feel comfortable

|

0 (0)

|

11 (7.1)

|

144 (92.9)

|

|

Not judgemental

|

2 (1.3)

|

10 (6.5)

|

143 (92.3)

|

|

Uses everyday language

|

1 (0.6)

|

20 (12.9)

|

134 (86.5)

|

|

Treats young patients like young adults

|

0 (0)

|

25 (16.1)

|

130 (83.9)

|

|

Reassuring of appointment privacy and confidentiality

|

3 (1.9)

|

36 (23.2)

|

116 (74.8)

|

|

Is a younger doctor

|

88 (56.8)

|

49 (31.6)

|

18 (11.6)

|

|

Important qualities in a GP clinic

|

|

|

|

|

Reception staff able to recommend youth-friendly GP for appointments

|

3 (1.9)

|

35 (22.6)

|

117 (75.5)

|

|

Can see a GP during after-school hours

|

2 (1.3)

|

37 (23.9)

|

116 (74.8)

|

|

Do not have to wait long to get an appointment

|

10 (6.5)

|

60 (38.7)

|

85 (54.8)

|

|

Nice waiting room and toilet facilities

|

14 (9.0)

|

82 (52.9)

|

59 (38.1)

|

|

Quiet, not overcrowded waiting room

|

14 (9.0)

|

89 (57.4)

|

52 (33.5)

|

|

Can see a GP without booking an appointment in advance

|

19 (12.3)

|

98 (63.2)

|

38 (24.5)

|

|

Longer appointments

|

16 (10.3)

|

102 (65.8)

|

37 (23.9)

|

|

Young patients’ names are not called out in the waiting room

|

93 (60.0)

|

44 (28.4)

|

18 (11.6)

|

Discussion

An established relationship with a trusted GP is the cornerstone of general practice, and 95% of adolescents we surveyed considered GPs to be their primary healthcare provider. Young people want appointment times available to them outside of school hours, and to have friendly reception staff who can recommend a ‘youth-friendly’ GP. Notably, young people would like to be asked about sexual health, mental health and substance use, even if they present for other reasons.

Good communication skills were highly valued by participants of this study. These young people valued practitioners who avoid medical jargon, listen, assure them about confidentiality, and respect their views and choices. There is a good correlation between doctor empathy and patient satisfaction, as well as a direct positive relationship with strengthening patient enablement in GP settings.13 Strategies that have the most benefit for strengthening the communication skills of trainee doctors include having the opportunity to practise communication skills, and having these skills modelled in a supportive environment where there is appropriate feedback from role models.14 Communication is a complex skill that warrants more effective teaching and learning.15 Van den Eerwegh and colleagues identified five phases that characterise the learning process of communication skills.15 These authors suggested that this supports the notion that longitudinal, structured training of communication skills will be more effective than single or isolated training moments.

Adolescents in this survey responded that they would like their GP to ask them about topics, including sexual health, mental health and substance abuse, even if this is not the reason for presenting – this sentiment is also reflected in literature that states that adolescents find such themes confronting to discuss.1,2,3,6,9 Lack of screening by health professionals has previously been attributed to a lack of time, lack of referral places if screening is positive, and lack of training or being uncomfortable delivering youth healthcare.16,17

The opportunity to improve adolescent healthcare access and delivery in the general practice setting is not confined to the consultation room. An inability to make an appointment at a convenient time acts a major barrier to healthcare use. Additionally, the survey showed that young people highly value approachable reception staff who are able to recommend a youth-friendly GP. The results from this study also support literature suggesting that it is not new or separate healthcare facilities that young people desire, but rather a positive, youth-friendly environment.

Study limitations

The study findings are limited by the single-school study site. However, the high response rate at the single-school site is a strength of the study. Unfortunately, there is a lack of comparative data from another school to analyse differences from schools without on-campus GP clinics. Additionally, as the study site was a school in regional Tasmania, the results may not be generalisable to metropolitan settings, where there is a greater range of adolescent healthcare services available. However, the results are an important guide to the delivery of healthcare to young people in other rural areas. There was a difference in the gender ratio of participants, with a larger proportion of female respondents. This may limit generalisability of the study findings to adolescent boys.

Conclusion

General practice plays an important role in youth health and 95% of adolescents in this study considered a GP to be their primary healthcare provider. Young people valued GPs with good communication skills. A greater focus on adolescent health and communication skills during undergraduate and postgraduate medical training might better prepare doctors for addressing unmet healthcare need among young people.

Implications for general practice

Practical ways to improve access for young people include approachable practice staff who can recommend a youth-friendly GP and availability of after school-hours appointments. GPs with good communication skills are highly valued by young people, and they would like to be asked about sexual health, mental health and substance use, even if they present for other reasons.

Authors

Laura Turner, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Leah Spencer, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Jack Strugnell, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Julian Chang, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Isabel Di Tommaso, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School Burnie, Tas

Magella Tate, medical student (final year), University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Penny Allen MPH, PhD, Research Fellow, University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas. penny.allen@utas.edu.au

Colleen Cheek RN, BSc, MIS, Research Fellow, University of Tasmania Rural Clinical School, Burnie, Tas

Jane Cooper BMedSc, MBBS, DRANZCOG, FRACGP, Practice Principal, Don Medical Clinic, Devonport, Tas

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Magella Tate, a fourth year medical student at the University of Tasmania and a member of this research team, who passed away in September 2015. We would also like to acknowledge the high school and on-site high school medical centre for their involvement in this research.