Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common, inherited cardiac disease with a prevalence of one in 500 people.1 HCM is defined by the presence of otherwise unexplained thickening (hypertrophy) of the muscular wall of the left ventricle.2 Diagnosis of HCM requires the exclusion of other potential causes of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), such as systemic hypertension, aortic stenosis, physiological change in strength-based athletes, Fabry disease and cardiac amyloidosis. The onset of HCM-induced LVH typically occurs during adolescence, although the condition can first manifest at any stage of life.3 An understanding of the key principles of assessing and treating patients with HCM, including screening family members, is an essential skill for all primary care physicians.

Pathogenesis of HCM

HCM is a heterogeneous condition with a genetic basis. However, affected patients within the same family who are known to possess an identical pathogenic mutation can exhibit marked phenotypic variation. Inheritance is generally autosomal dominant with variable penetrance,4,5 and up to 90% of pathogenic HCM mutations are sarcomeric (ie involving structural or regulatory genes of the contractile unit of the cardiac muscle fibre).6 The genes for β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7) and myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3) account for approximately three-quarters of documented pathogenic HCM mutations. Most pathogenic HCM mutations are family-specific, and the presence of compound mutations (ie two heteroallelic mutations in the same gene) or double mutations (ie two heterozygous mutations in the same gene) in an individual is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD).7

Histopathological changes in HCM are characterised by cardiac muscle cell (cardiomyocyte) disarray, with an irregular arrangement of abnormally shaped cardiomyocytes containing bizarre nuclei, and increased extracellular connective tissue.8

Most, but not all, patients with HCM have an obstruction to the outflow of blood from the left ventricle, which is termed left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. Thus, the label ‘hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy’ (HOCM) cannot be applied to all patients with HCM. LVOT obstruction arises from a combination of fixed LVH of the basal interventricular septum and dynamic systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve leaflets (because of a Venturi effect). Approximately one-third of patients with HCM manifest echocardiographic features of LVOT obstruction at rest, one-third with exercise, and one-third show no obstruction whatsoever.9

Clinical manifestations of HCM

Adolescents with HCM are often asymptomatic. The most common symptom – exertional dyspnoea – results from a combination of LVOT obstruction, mitral valve regurgitation, ventricular diastolic dysfunction and/or ventricular systolic dysfunction. HCM predisposes to any cardiac arrhythmia, particularly atrial fibrillation. A small proportion of patients (about 3.5%) develop end-stage systolic heart failure, which may necessitate cardiac transplantation.10

Adolescents are increasingly diagnosed with HCM in the absence of symptoms. For example, HCM may be detected in an adolescent during family screening of an adult relative diagnosed with the condition. An abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG) or incidental auscultation of a systolic cardiac murmur (because of LVOT obstruction and/or mitral regurgitation) are other mechanisms by which HCM can be detected in an asymptomatic adolescent.

The annual mortality rate of HCM is about 1%11 and it is the most common cause of SCD in young athletes.12 In fact, SCD may be the first presenting clinical manifestation in HCM. Current guidelines13 identify several ‘major’ risk factors for SCD, which, if present, are indications for insertion of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for primary prophylaxis. These major risk factors include:

- family history of SCD

- unexplained syncope

- documented non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

- maximal left ventricular wall thickness ≥30 mm.

However, the current risk stratification approach to HCM requires further optimisation as some at-risk patients are not identified by these risk factors.

Investigating HCM

A comprehensive assessment of an adolescent with suspected HCM requires confirming the diagnosis of HCM and assessing the severity of the condition. An incorrect diagnosis of HCM may lead to excessive diagnostics testing and unnecessary anxiety for the adolescent and their family.

Electrocardiogram

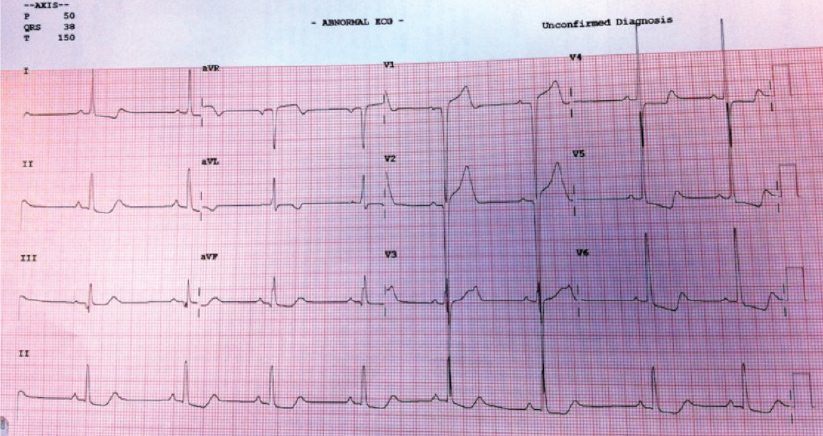

An abnormal 12-lead ECG can raise the possibility of HCM in an adolescent, particularly if large QRS voltages associated with ST segment and/or T wave repolarisation abnormalities are seen (Figure 1). Distinguishing physiological from HCM-related ECG changes in a young athletic adolescent can be challenging. Furthermore, an ECG can be normal in up to 10% of patients with HCM.14

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram (ECG) of an adolescent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy with associated ST segment repolarisation abnormalities are classical ECG findings in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, although abnormalities may be subtle or absent in some patients.

Resting echocardiogram

The diagnosis of HCM is most commonly made by cardiac ultrasonography (ie echocardiography). Echocardiography is the most widely available and established means of assessing ventricular structure and function. Important indices derived from echocardiography in the setting of HCM include:

- whether left ventricular systolic function is preserved

- the pattern and degree of LVH

- whether LVOT obstruction is present (at rest and/or with Valsalva manoeuvre)

- presence and degree of mitral regurgitation (due to systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve).

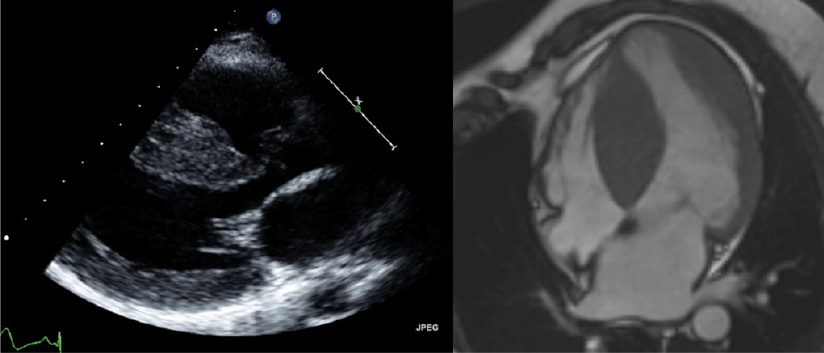

Any degree of unexplained LVH (ie left ventricular wall thickness ≥11mm) raises the possibility of HCM, particularly in an adolescent where changes secondary to persistent systemic hypertension are far less common. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy is the most commonly observed pattern of LVH (Figure 2); however, apical and concentric variations also occur. Left ventricular systolic function is usually normal in patients with HCM.

Figure 2. Imaging of asymmetric septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Echocardiographic (left panel) and cardiac magnetic resonance (right panel) imaging showing severe asymmetric septal hypertrophy because of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a male, 14 years of age.

Exercise stress echocardiogram

A treadmill stress echocardiogram provides additive diagnostic and prognostic information in HCM. Exercise-induced dynamic LVOT obstruction (which occurs in one-third of patients9) can manifest with exertional symptoms (eg dyspnoea, presyncope, syncope) and/or a significant drop in blood pressure with exercise. Physical exercise may also precipitate arrhythmias. The ability to achieve >100% of an age-predicted and gender-predicted metabolic equivalent has been shown to portend an excellent cardiovascular prognosis.15

24-hour Holter monitor

A Holter monitor can identify subclinical arrhythmia(s), and is particularly important in establishing the presence of ventricular tachycardia, a major risk factor for SCD.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) has high spatial and temporal resolution that, with concurrent intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast, can non-invasively characterise myocardial tissue. Additionally, CMRI possesses excellent structural and functional assessment capabilities. CMRI is considered the gold standard of ventricular volumetric assessment and can also evaluate myocardial fibrosis. CMRI, however, is expensive and has limited availability.

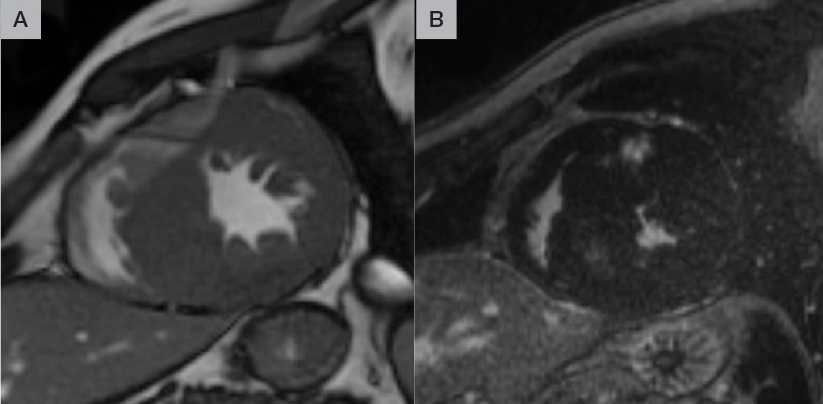

Hyperintense areas of myocardium detected by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences in HCM represent replacement fibrosis histologically16 and predict a worse outcome.17 LGE is identified in up to 80% of HCM patients,18 typically within the interventricular septum or within the left ventricular wall at the points of insertion of the right ventricle (Figure 3).19,20

LGE is likely to be an independent risk factor for SCD in HCM. The presence, but not quantity, of LGE has been associated with the occurrence of ventricular tachycardia, suggesting that myocardial fibrosis represents an arrhythmogenic substrate in HCM.21

Figure 3: Late gadolinium enhancement imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Pre-contrast (A) and post-contrast (B) short-axis images at the mid-ventricular level; hyperintense regions post-contrast indicate late gadolinium enhancement

Genetic testing in HCM

Even in patients with a documented family history of HCM, a pathogenic mutation can be identified only 65% of the time.22 Patients who have HCM with a recognised pathogenic HCM mutation are younger when first diagnosed,23 have more LVH,23 and are at a greater risk of symptom progression and adverse cardiac outcomes.24 Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides rapid and relatively cost-efficient testing of known HCM genes to identify pathogenic mutations.25 Currently, however, the primary clinical role of genetic testing in HCM is to facilitate cascade screening within a family rather than confirming a diagnosis of HCM in an individual.

Treatment of HCM

Management of HCM in adolescents may consist of lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy, septal reduction therapy, ICD insertion and family screening.

Lifestyle modification

Adolescents with HCM are advised to cease playing competitive sport. This restriction may be considered excessive, particularly in a healthy and athletic young person, but has the potential to prevent SCD. However, in most adolescents with HCM, the benefits of regular non-competitive exercise outweigh the risks.26 As a result, recommendations as to which exercise activities can be pursued relatively safely in adolescents with HCM have been created.27 For example, low-intensity or moderate-intensity exercise, such as jogging, cycling (10–15 km/h), lap swimming and golf, may be permitted on an individual basis, while high-intensity sports such as football and squash should be avoided.

Pharmacotherapy

First-line medications in HCM, such as beta-blockers (eg metoprolol, atenolol) and verapamil, are indicated in symptomatic patients. There is no evidence suggesting any prognostic benefit from any medication in HCM.

Endocarditis prophylaxis

Current antimicrobial guidelines28 do not recommend routine antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental or surgical procedures in adolescents with HCM, even in the presence of LVOT obstruction.

Septal reduction therapy

Surgical septal myectomy is considered in adolescents with disabling symptoms because of severe LVOT obstruction (ie peak LVOT gradient ≥50 mmHg) where medical therapy has been ineffective. Alcohol septal ablation is rarely performed in adolescents. It is preferable for septal reduction therapy to occur in a specialised HCM centre.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator insertion

In adolescents with HCM who manifest at least one major risk factor for SCD, an ICD should be strongly considered.

Family screening

Comprehensive management of an adolescent with HCM involves a systematic approach to family screening for the condition. Screening for HCM with a regular physical examination, ECG and echocardiogram is recommended for all first-degree relatives. Given the possibility of disease onset later in life, screening of first-degree relatives should be repeated regularly according to age (every 12–18 months for those aged 10–20 years, every two to three years for those aged 20–30 years and every three to five years for those aged >30 years). Screening of non–first degree relatives can also be considered.

Identification of a pathogenic HCM mutation can simplify this screening process. For example, a sibling of an affected adolescent with HCM can undergo cascade genetic screening for their family-specific pathogenic HCM mutation. For relatives who possess this causative mutation (ie genotype-positive), regular conventional screening with ECG and echocardiography is recommended. Relatives who lack the family-specific HCM mutation will not, to all intents and purposes, be at risk of developing HCM and are generally removed from ongoing surveillance.

Case

SW is 16 years of age and has non-obstructive HCM. His mother was diagnosed with the condition and subsequently underwent genetic testing, which showed that she had a pathogenic HCM mutation involving the MYH7 gene. SW was subsequently found to carry this same family-specific HCM mutation. SW was reviewed regularly at a paediatric cardiology unit, and had serial ECGs and echocardiograms.

Asymmetric septal hypertrophy first manifested at the age of 14 years. A CMRI confirmed a maximal septal thickness of 22 mm, with associated late gadolinium enhancement within the interventricular septum. Holter monitor findings were unremarkable. SW had excellent exercise capacity during a stress echocardiogram without inducible LVOT obstruction or arrhythmia. He was commenced on a low dose of a beta‑blocker (atenolol 25 mg daily) for exertional dyspnoea, with some subjective benefit. SW played no competitive sport; however, he had a cardiac arrest while running to catch a bus. He made a full recovery and a cardiac defibrillator was implanted. SW has a younger sibling who also has HCM.

Key points

- HCM, the most common inherited cardiac condition (prevalence one in 500), can present in various ways, ranging from an incidental diagnosis to sudden death.

- Early recognition of HCM has the potential to save lives.

- GPs should consider arranging an ECG and echocardiogram for any adolescent with cardiovascular symptoms, a systolic cardiac murmur, or a family history of cardiomyopathy or SCD.

- Early referral to a paediatric cardiology department should be made for any adolescent with LVH. Medical therapy and/or septal reduction therapy are generally reserved for patients who are symptomatic.

- Identifying adolescents at a heightened risk of SCD is challenging, and implantation of a cardiac defibrillator is considered in high-risk patients.

- HCM is a prototype for inherited cardiomyopathies, and GPs should be aware of, and in some instances facilitate, family screening recommendations.

Author

Andris H Ellims MBBS (Hons), PhD, FRACP, Director, HCM Clinic @ The Alfred; Victoria Heart, Windsor, Vic. A.Ellims@alfred.org.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.