Otalgia, or pain localised to the ear, is a common symptom seen in general practice, emergency departments and otolaryngology clinics. Approximately 4% of general practitioner (GP) encounters are solely for ears.1 Most of the common causes of otalgia are benign conditions that can be effectively treated with routine management; however, there are more sinister diagnoses that need to be considered in some cases. Unfortunately, there is no straightforward algorithm for the assessment of otalgia.2 To understand otalgia and its causes and complications, a brief appreciation of anatomy is required.

The major anatomical structures of the external ear (auricle) are the helix, ear lobe, tragal cartilage, conchal bowl, external auditory meatus, and canal and lateral tympanic membrane. The middle ear consists of the medial tympanic membrane and ossicles, and connects via the eustachian tube to the posterior nasopharynx. The nerve supply for sensation in the ear arises from several cranial nerves including the trigeminal nerve (CNV), facial nerve (CNVII), glossopharyngeal (CNIX) and vagus nerve (CNX) as well as the cervical plexus (Table 1).3–5 In the ear, pain fibres in the nerve endings are stimulated by distension of skin due to swelling or compression against bony or cartilaginous structures.6 These same nerves also supply multiple head and neck structures, and therefore make otalgia a complex symptom given the possibility of referred pain.

Table 1. Nerve supply to the ear3–5

|

| Nerve | Supply |

|---|

| Great auricular (C2, C3) |

Cranial surface of auricle and the lower part of the lateral surface of auricle |

| Auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve |

Upper part of the lateral surface and most of the meatal skin |

| Facial nerve |

Posterior–inferior portion of the external ear canal and adjacent tympanic membrane |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve tympanic branch |

Mucosal surface of tympanic membrane |

| Vagus – auricular branch ‘Arnold’s nerve’ |

Supplies small areas of skin on the cranial auricular surface, posterior wall and floor of the meatus and adjoining part of the tympanic membrane |

Aetiology

The aetiology of otalgia can be broadly divided into primary and secondary causes (Table 2). Primary causes are those that originate in the ear and are a direct cause of pain through stimulation of nociceptor fibres. Secondary causes are those that the patient feels have originated from the ear, but in fact are referred from other sources and require a higher index of suspicion to determine the precise aeitiology. Additionally, primary otalgia seems to be more common in children and secondary otalgia more common in adults.7

Table 2. Causes of otalgia

|

| Primary otalgia | Secondary otalgia |

|---|

| Infection |

Dental inflammation and infection10,11 |

| Trauma and foreign bodies |

Temporomandibular joint disorders12,13 |

| Impacted cerumen8 |

Trigeminal neuralgia2 |

| Otologic neoplasms9 |

Head and neck cancer14 |

| |

Eagle’s syndrome15 |

| |

Temporal arteritis |

The primary causes of otalgia are often benign and present as straightforward cases to the experienced GP. Infection, trauma, foreign bodies and impacted cerumen are the common conditions usually diagnosed on otoscopy. Primary neoplasms of the ear are rare and usually clearly identified when they occur on the auricle and originate in the peri-auricular region. Cancers of the temporal bone and external auditory canal are rarer still, and are often only diagnosed when more advanced signs appear, but should be considered in a patient with otalgia and a chronic ear discharge.16 Skull-base osteomyelitis (or malignant otitis externa) should always be considered in patients who are immunosuppressed or have diabetes with severe otalgia and a history of otitis externa. The organisms typically responsible include Pseudomonas but may also be fungal. The pain is often described as severe and throbbing in nature that radiates into the jaw. As the disease progresses, it causes cranial nerve palsies, initially involving VII (facial nerve), then XII (hypoglossal nerve) and X (vagus nerve). There is typically granulation tissue seen in the floor of the ear canal. This should be biopsied by an ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon as the differential diagnosis is squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) viral infection presents with pain, vesicles involving pinna/external auditory meatus and facial nerve palsy.

If the cause is not obvious, secondary causes of ear pain are considered. Odontogenic causes are an extremely common cause of referred otalgia; these causes occur in up to 63% of cases10,11 and include inflammation and infection of dental structures, particularly associated with the posterior teeth.11 Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are another important cause of secondary otalgia and some patients with TMJ disorders may also present with other otological symptoms such as tinnitus and vertigo.12 The pain of TMJ disorders reflects either the joint or muscles associated with jaw movement; therefore, exacerbation of pain associated with chewing may indicate the source of pain.13 A brief examination of the teeth and jaw may allow commencement of basic management and avoid over-investigation.

Trigeminal neuralgia can also present with otalgia.4 This diagnosis is usually clear; however, when the patient describes unilateral attacks of pain that commence abruptly, last up to two minutes and are extremely excruciating.17 It is reported that neuralgia can occur in other cranial nerves and the consistent feature is that the pain should follow the distribution of the nerve.

All cancers of the head and neck – usually squamous cell carcinomas – need to be considered as a secondary cause of otalgia in patients who have an otherwise normal otology history and examination.14 Of particular importance are neoplasms in the oropharyngeal region (soft palate, posterior pharyngeal wall, palatine tonsil or tongue base), which can present with deep, intense otalgia.14 Patients with cancers in this region may have additional symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia and sore throat, or may be otherwise asymptomatic. Risk factors include chronic alcohol consumption and tobacco exposure. Cervical lymphadenopathy is a common examination finding as these cancers often present at advanced stages.18 Examining the oropharynx by direct inspection and palpation, as well as the neck, is critical given that an earlier diagnosis will enable a better chance at curative treatment. A complete examination of the oropharynx does require nasal endoscopy by an otolaryngologist and therefore unexplained otalgia should be referred early.

Eagle’s syndrome15 may be secondary to a calcified stylohyoid ligament, which can be palpable in the tonsillar fossa.

Assessment

History

The severity of otalgia alone is unlikely to reflect the seriousness of the aetiology.19 A complete otology history is essential for determining if the cause is primary and therefore a history should be routine in a patient presenting with otalgia. In addition to a thorough review of the pain, explore symptoms of otorrhoea, hearing loss, vertigo, aural fullness and tinnitus. For some patients this minimum history is all that is required to make the correct diagnosis and commence prompt treatment. The time course will further support the likely cause of disease. Generally, shorter time frames suggest a primary or benign cause and longer time frames suggest a secondary cause. If the cause is not almost immediately apparent then associated symptoms should be sought from the other anatomical regions supplied by the same nerves innervating the ear. Enquire about associated symptoms involving the oral cavity, including dental history, oropharyngeal symptoms including history of tonsil infections, and nasal and sinus passage symptoms.

Some red flags that should prompt a more detailed history, examination and investigation are provided in Box 1. The medical history should also be logical (eg the seasonal occurrence of ear infections). A smoking and alcohol history should be taken from every patient given the association of smoking and alcohol consumption with head and neck cancers that can be difficult to diagnose20 and, even if not relevant to the current clinical problem, may present an opportunity for primary prevention.

Box 1. Red flag history points

|

Red flag

- Associated oropharyngeal symptoms (dysphagia, dysphonia, odynophagia, haemoptysis, weight loss, smoking history), which may suggest a head and neck cancer

- Progressive or sudden onset hearing loss

- Eye symptoms (loss of vision, black spots)

- Immunosuppressed or diabetes mellitus which may allow an infection to rapidly progress

|

Examination

Examination should be directed by the history, but should generally begin with general inspection of the external ear including pre-auricular and postauricular regions, as well as otoscopic examination of the auditory canal and viewing the tympanic membrane.21 If there is an abnormal finding in the ear then the examination should always progress to examination of the cranial nerves to assess for complications.2 A patient with a bulging tympanic membrane that is erythematous is a key finding in acute otitis media (AOM). Purulent discharge in the auditory canal probably reflects otitis externa. Alternatively, it can represent a perforated suppurative otitis media, which can sometimes be difficult to differentiate. Pain on insertion of the otoscope is a reliable sign that the cause is otitis externa. Acute mastoiditis is a complication of AOM and a clinical diagnosis with key findings including postauricular swelling and erythema, tenderness and protrusion of the auricle.22 Obliteration of the postauricular sulcus and possible swelling involving the postero–superior external meatus may also be seen.

If the ear and otoscopic examinations do not reveal a clear cause for otalgia then a complete head and neck with cranial nerve examination should be performed given the possibility of referred pain. This part of the examination must include inspection and palpation of the oral cavity and oropharynx with concentration given to the teeth, TMJ, tongue, soft palate, posterior pharyngeal wall and tonsils. All dentures must be removed to facilitate adequate examination. Opening and closing the mouth may reveal trismus, as well as audible or palpable crepitus suggestive of a TMJ abnormality. The anterior nasal cavities can also be inspected with good lighting. Full neck palpation in all regions for masses or lymphadenopathy is important for diagnosis of metastatic disease. Lateral palpation over the TMJ may reveal dysfunction and pain directly at these joints.19

Investigations

Few investigations are required on first review of the patient with otalgia, as history and examination are usually sufficient to commence appropriate first-line management for common conditions. However, in primary otalgia that is not straightforward, or in the case of secondary otalgia, investigations should be considered. Ear swabs should be done only for recurrent or chronic otitis externa.23 Hearing tests should always be considered for patients with associated hearing loss, especially if this does not improve with appropriate management of the presumed cause for otalgia. Imaging is performed when a patient is considered to be at high risk of malignancy; therefore, the radiologist may be the first to identify the source of referred ear pain.4

Management

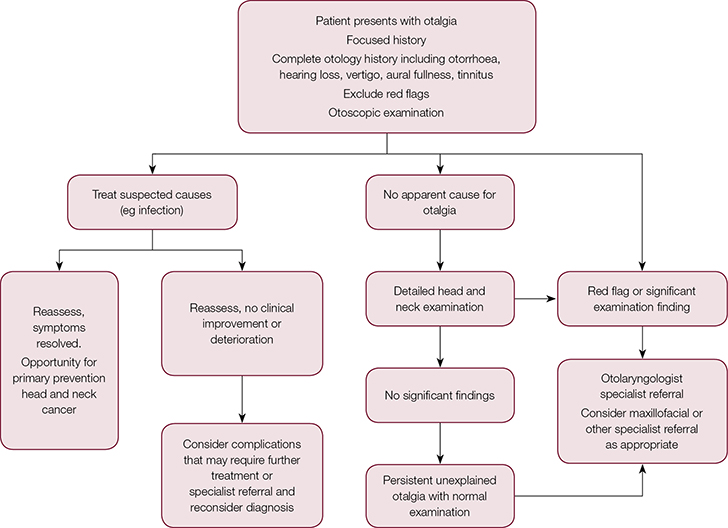

Management of otalgia involves treating common infections while being aware of their possible complications and knowing when to reconsider the diagnosis or refer. Analgesia alone is rarely the sole treatment and a cause should always be sought.

|

| Figure 1. Management of otalgia |

When to refer

Outpatient specialist referral is indicated in patients who present with persistent or unexplained otalgia without an apparent cause and a normal examination.19,21 A flexible nasal endoscopy can be performed by an otolaryngologist to exclude a lesion that may be a squamous cell cancer not visible to the GP. It is difficult to identify the correct region and modality when undertaking an imaging investigation based on otalgia alone, and specialist review may be required before any imaging is carried out. Consider referral to a dental or maxillofacial specialist if the symptoms appear to be odontogenic in cause. If the suspected diagnosis is not responding to the usual treatment within the normal time frame, reconsider the diagnosis.

Case

Beatrice, 21 years of age with no medical history, presented to her GP with acute on chronic bilateral otalgia. The pain had been intermittent over the past three months, but had increased in intensity and become constant over the past two days. The pain was described as a dull ache deep inside her ears, with associated aural fullness but no associated ottorhoea, tinnitus, vertigo or hearing loss. There was no history of trauma to the region. On examination, Beatrice was afebrile. No abnormality was found in the external ear, auditory canals and tympanic membranes on otoscopic examination. There were no abnormal lesions in her oral cavity, no pain on palpation of her dentition, mouth opening was greater than three finger breadths, occlusion was normal, and tonsils appeared symmetrical with no mucosal abnormality. There was no palpable cervical lymphadenopathy or masses in her neck. She was tender over the bilateral TMJ on palpation with associated crepitus on mouth opening. The tenderness also extended over the masseter and temporalis muscles.

Given her history of chronic otalgia, Beatrice was referred to an otolaryngologist for further assessment. In addition to repeating the history and examination, the otolaryngologist performed a nasal endoscopy, which revealed no abnormal mucosa down to the level of her vocal cords, and a microscopic examination, which excluded a lesion or deep infection related to the ear. Beatrice was also referred to a maxillofacial surgeon for assessment of referred otalgia secondary to TMJ dysfunction or a dental source. Following review by a maxillofacial surgeon, TMJ dysfunction was confirmed as a likely cause of her pain. She was advised to trial oral anti-inflammatory medications and a soft diet. Computed tomography (CT) of her TMJ was organised to exclude a structural abnormality or a degenerative process, and a dental referral was made for assessment of a splint. A review appointment was made to consider the administration of botulinum toxin injections into her temporalis and masseter muscles if there was no further improvement.

Conclusion

In a patient who presents with otalgia that does not have a clear cause, or if the suspected cause does not respond to treatment as expected, consider red flags and exclude a more sinister cause for the symptoms.

Authors

Elizabeth Harrison MBBS, Non-accredited otolaryngology registrar, Gold Coast University Hospital, Southport, Qld. Elizabeth.Harrison2@health.qld.gov.au

Matthew Cronin FRACS (OHNS), MBBS, Otolaryngologist and Head and Neck Surgeon, Gold Coast University Hospital, Southport, Qld; Ipswich Hospital, Ipswich, Qld; Pindara Private Hospital, Benowa, Qld

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.