Cancer is a major cause of illness in Australia. It is estimated that more than 123,000 people were diagnosed with cancer in 2014.1 Pleasingly, five-year survival rates have improved from 46% in 1982–86 to 67% in 2007–11.1 Around 4% of the population, or around one million Australians, have a personal history of cancer.2

Survivors may encounter a range of potential effects as a result of cancer and cancer treatments, including physical, psychosocial, practical and existential effects.3 These may pass relatively quickly (eg hair loss or nausea), or may be long term or permanent (eg infertility). Some effects – so called ‘late effects’, such as heart failure or second cancers – may not arise for months or years after completion of treatment. Most survivors require ongoing care following completion of treatment.3

A shortage of oncologists has been projected, putting significant strain on current models of follow-up for cancer survivors, which are dominated by specialist-led review.4 Patients with cancer have significant engagement with general practitioners (GPs) prior to diagnosis, during and after treatment, and may prefer to have follow-up care coordinated by their GP.5–8

There are increasing calls for formalised models of shared care, integrating care between oncology and primary care teams.3,9–12 Shared care appears to result in improved management of comorbid illness, enhanced preventive care, as well as appropriate cancer-specific management.13–15 The majority of GPs have indicated a willingness to be involved in the post-treatment care of cancer survivors;16–18 however, they have also indicated a need for further training.19–21 There are also calls to focus attention on improving discharge to primary care and on care transitions.3,11,12,22,23

In 2011, the Victorian Department of Health initiated the Victorian Cancer Survivorship Program (VCSP). This funded six projects to pilot different cross-sector, patient-centred models of care across a range of health settings and populations of survivors.24 Evaluation of these pilots supported aligning post-treatment cancer care with chronic disease management models and facilitating engagement with primary care. A key finding from the VCSP was the need for more survivorship education for a variety of health professionals.

Building on findings from the VCSP projects, we sought to pilot a general practice (primary care) cancer survivorship placement program. This program was based on information gained from related projects, including the Program of Experience in the Palliative Approach (www.pepaeducation.com/about.aspx).The principal objective was to determine whether primary care and hospital-based oncology specialists found that the clinical placement was feasible and of clinical and professional value, and provided an opportunity for knowledge and skills transfer.

Methods

Design

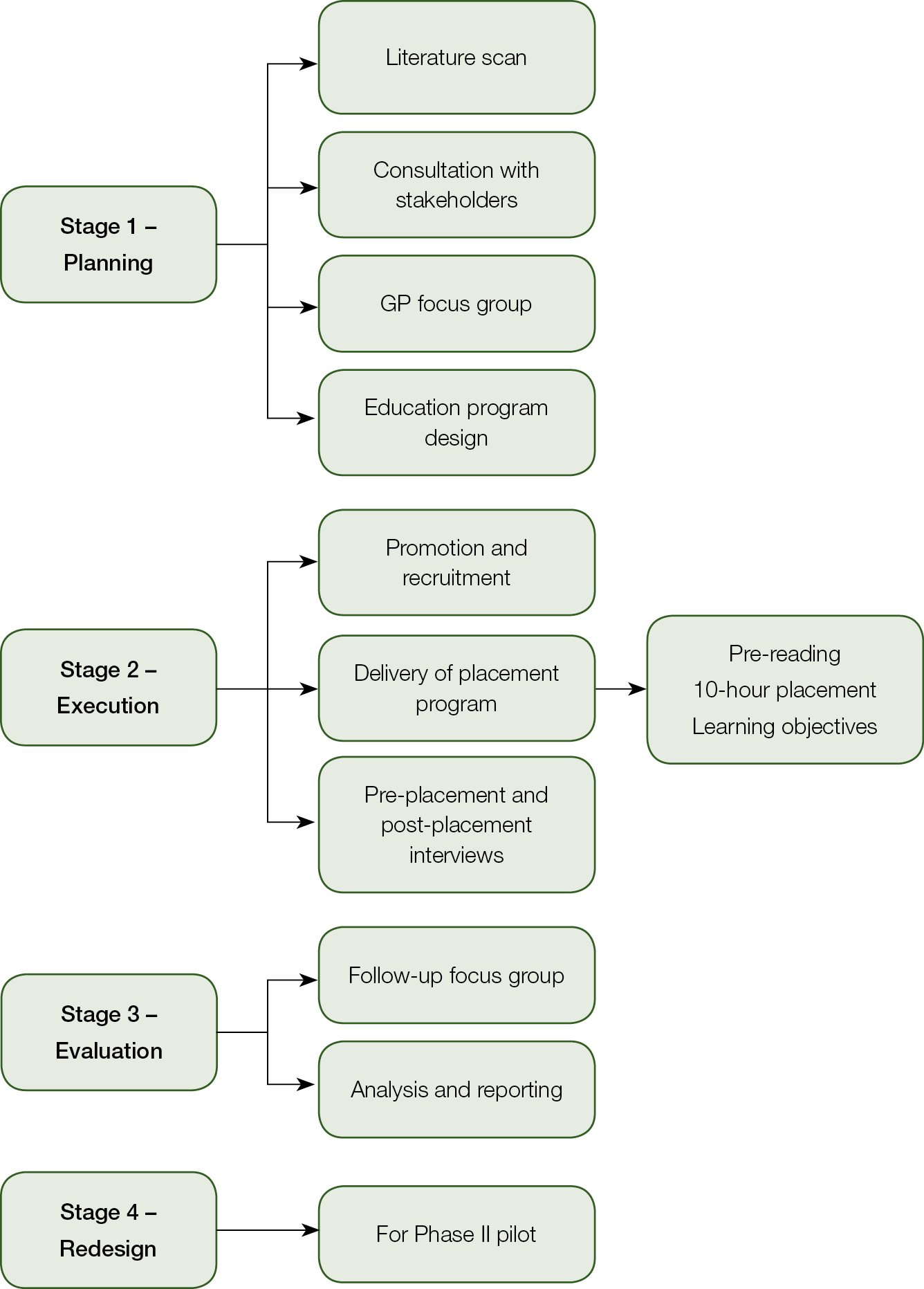

With funding provided by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, the placement program was undertaken at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (Peter Mac), a comprehensive cancer centre in Melbourne. The Human Research Ethics Committee at Peter Mac approved the study (Project 14/170L). Figure 1 outlines the program development. A project advisory group comprised representatives from Peter Mac, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association, Australian Association of Practice Managers, as well as GP academics and researchers, and a consumer.

A rapid environmental scan of Australian and international literature was completed to inform the design of the program. In addition, a general practice focus group was held to understand the views of general practice teams regarding a clinical placement, barriers and enablers to shared care, and preferences around program design.

|

| Figure 1. General practice placement in cancer survivorship project map |

Deliverables

We sought to pilot a clinical placement where GPs and general practice nurses (GPNs) worked with hospital-based oncology teams from two or three of five cancer clinical services (breast, uro-oncology, skin and melanoma, lower gastrointestinal, late effects). GPs and GPNs received pre-readings and a video. They also attended multidisciplinary meetings and outpatient clinics for a total of 10 hours to observe and, ideally, participate in decision-making and treatment planning for patients with early-stage (potentially curable) disease and patients with advanced (metastatic, incurable) cancers; the emphasis, however, was on the post-treatment phase. The program aimed to recruit at least four GPs and eight GPNs.

Learning outcomes

At the completion of the clinical placement, it was hoped that participants would achieve the following program learning outcomes:

- identify the role of shared care in post-treatment cancer care and mechanisms to strengthen links between generalist and specialist cancer care providers

- relate the decisions made at diagnosis and during active treatment to the impact on cancer survivorship and post-treatment care in primary care

- recognise the value of collaboration with multidisciplinary teams to provide best patient care, and reflect on the feasibility and clinical and professional value of a clinical placement.

Placements

A one-off financial stipend was provided to compensate the participants for taking time out of practice. The program attracted continuing professional development (CPD) points (40 category 1 for GPs and 10 CPD points for GPNs). Generalists received pre-placement materials, including general survivorship information relevant to primary care, and were also asked to review short videos describing issues relevant to cancer survivors.

Evaluation

All participants (cancer centre specialists and generalists) were invited to participate in pre-placement and post-placement semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups. Pre-placement interviews focused on personal learning objectives, perceived personal and organisational value of participation, and barriers and enablers to participation. Post-placement interviews focused on whether personal and program learning needs were met, perceptions of change in attitudes to post-treatment shared care, and the clinical and professional value of the placement. Interviews were recorded and transcripts were analysed to identify themes.

Results

Program description

The program recruited 16 GPs and 12 GPNs from general practice and community health settings in metropolitan, outer metropolitan and regional Victoria. We also recruited nine oncology specialists working with breast (2), uro-oncology (2), skin and melanoma (1), lower gastrointestinal (2) and late effects (2) cancer clinical services. A waiting list for possible future placements was created as the program was oversubscribed.

Program evaluation

Twenty-seven generalists and five specialists participated in post-placement evaluations. All participants felt that both the program and their personal learning goals were partially or completely met; all participants felt that the program was relevant to their clinical practice. The program was perceived as being clinically and professionally valuable and all respondents indicated they would recommend the placement to colleagues.

Feasibility

According to the generalists in the program, key enablers for participation were:

- a strong interest in the clinical management of people with cancer

- support and encouragement from their own workplace to attend

- facilitation and support provided by the project manager.

Generalists reported that the stipend (while minimal) recognised their time out of clinical practice and the impact this had on their business. CPD points provided confidence that the placement would offer a quality clinical experience.

Cancer specialists identified their passion for providing a clinical learning environment and their enthusiasm for the project aims as strong motivators to participate. Specialists rated highly the opportunity to collaborate with generalists.

Knowledge and skills transfer

Generalists felt the placement reinforced their role in post-treatment care and that any knowledge and skills gaps could be easily met through education and support from specialists. There was a perception of knowledge and skills transfer, and raised awareness of chronic disease management protocols that might support post-treatment survivorship care. Exposure to long-term follow-up and treatment consequences was limited unless generalists attended the late effects clinics. Specialists identified that the placement program provided them with a greater understanding of general practice and the role of chronic disease management. Respondents reported that knowledge transfer facilitated the building of collaborative relationships and breaking down of cross-sector barriers. Both clinical groups recognised the need to better facilitate patient care across hospital and community sectors.

Perspectives regarding shared care

Participants noted challenges to the delivery of shared care for cancer survivors. Five themes were described:

- Confidence and empowerment to work in shared care

- Workflow constraints

- Workforce capacity and competency

- Inadequate communication to support clinical handover

- Generalists’ knowledge gaps around treatments and short-term and long‑term consequences (Table 1).

Future program development

Participants were asked for suggestions to improve the program. The specialists wanted an increased involvement in the program design to facilitate cross-sector learning; noted the lack of time to prepare; and wanted the inclusion of the whole team in planning and delivery. The generalists indicated a preference for structured education and quality improvement activities. They identified a need for education in new therapies and treatment options, side effects of therapies and how these impact comorbidities. Some generalists reported that the clinical placement did not provide enough opportunity to describe the care model in primary care.

Discussion

The aim of the program was to investigate if a clinical placement was feasible and of clinical and professional value, and provided an opportunity for knowledge and skills transfer. The program was shown to be highly feasible and was oversubscribed, which resulted in a waiting list. All participants reported that the program was clinically and professionally valuable, and all would recommend the program to a colleague. Participants also indicated knowledge and skills transfer.

Generalists and specialists described gaining a better understanding of each clinical group’s contribution to cancer care. They expressed a desire to better align care pathways to improve survivorship care. Participants expressed enthusiasm to improve the quality of survivorship care and that the placement reinforced views that post-treatment best-practice care should include general practice.

The program also yielded rich additional information that described attitudes to shared cancer care, and a narrative on the barriers to transitioning and integrating care with general practice. These findings are consistent with other work that supports the willingness of generalists to be involved in follow-up cancer care while recognising timely communication, geographical location, adequate training and support, and time constraints as significant barriers.9,25 General practice may be a preferred setting for follow-up, as long as GPs are provided with clear guidance and have pathways to enable the patient to rapidly re-enter into specialist care, if required.25 Evidence indicates that follow-up in primary care is safe and may be associated with improved patient satisfaction and lower costs.26

This project has its limitations – it was conducted at a single centre with a small number of participants. Specialists had limited opportunities for learning from attending generalists as they were actively delivering clinical care while simultaneously supporting generalists as visitors. Specialists also reported a lack of opportunity for pre-planning to better prepare for the placement and subsequent engagement with visitors. Generalist participants in this study were self-selected and may have had a particularly strong interest in this clinical area. They may not be representative of the broader primary care community.

Table 1. Challenges to providing shared care

|

Findings

|

Quotes from generalists

|

|---|

|

Confidence and empowerment to work in shared care

|

‘It did give me confidence in that there were some common treatment pathways that if we were made aware of them early on … we would be in a better position to support our patients.’

|

|

Workflow constraints

|

‘So I could see that they [specialists] were working as a multidisciplinary team. I still think we as GPs are sitting on the outer in relation to that team.’

|

|

Workforce capacity

and competency

|

‘We provide different capabilities within different clinics, but we probably need to define the sorts of characteristics that a practice should have to support shared care as opposed to just the characteristics of a practitioner.’

|

|

Inadequate communication to support clinical handover

|

‘The specialists write [letters] at the end because it’s for them, it’s a memoir for them. It’s not necessarily seen as part of the continuity of care … they are not necessarily writing something to handover to somebody else.’

|

|

Generalists’ knowledge gaps around treatments and short-term and long‑term consequences

|

‘We need more information about some of those common tumours, the way they’re being treated, what the treatment protocols and pathways are so that we can at least say to the patient at the start of the journey this is what is likely to happen.’

|

Following this pilot, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services has provided funding to enable the project team to:

- develop a toolkit to support other sites in order to conduct placement programs

- develop information materials for primary care providers about post-treatment care (based on findings from this pilot work)

- coordinate an enhanced placement program for GPs and GPNs at three clinical sites.

A key focus of the second phase will be on strategies to ensure bidirectional learning between generalists and oncology professionals.

Authors

Judy Evans RN, GradCertPN, MHAdmin, Project Manager Education, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, a Richard Pratt legacy, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Vic

Linda Nolte BHSc (Nutrition and Dietetics), GradDipHSMgt, Manager, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, a Richard Pratt legacy, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Vic

Amanda Piper BSc, GCert Bus, MPH, MHA, Acting Manager, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, a Richard Pratt legacy, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Vic

Liz Simkiss BAppSc (ConsSc), Senior Project Officer Cancer Strategy & Development, Clinical Networks and Cancer & Specialty Programs, Health Service Performance and Programs, Department of Health and Human Services, Melbourne, Vic

Kathryn Whitfield AdvDipMRA, BA, GradDipHRM/IR, GradDipHlth (Eco and Health Program Evaluation), MCom (Hons), MHScience (Public Health Practice), Acting Assistant Director, Cancer Strategy and Development, Clinical Networks and Cancer & Specialty Programs, Department of Health & Human Services, Melbourne, Vic

Michael Jefford MBBS, MPH, MHlthServMt, PhD, GCertUniTeach, GAICD, FRACP, Associate Professor, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, a Richard Pratt legacy, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Vic. Michael.Jefford@petermac.org

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.