ost medical incidents are the result of human error; however, human error can be induced, for example, by complex work processes or prolonged hours.1,2 Healthcare services are complex and prone to errors.1,3

An active error is a mistake that has actually been made; for example, administration of an incorrect vaccine, which can be addressed by counselling staff to check the vaccine before administration. However, this does not reduce the chance of this error occurring again. A latent error is an error in a process that allowed the mistake to occur. For example, two similarly labelled vaccine ampoules could be interchanged. Some latent errors are hidden, for example, a computer software problem where recalls cannot be generated for a certain category. Staff can become accustomed to working around a latent error without realising it.1,4

For every clinical incident affecting a patient, there are 3–300 near misses.3 High-risk industries such as the aviation industry have been operating incident reporting systems for accidents and near misses since the 1950s and there have been significant benefits to safety.3 Morbidity and mortality clinics are an established part of risk reduction in secondary and tertiary medical care.5 However, this process has not been well established in general practice.6 External incident review committees (IRC), which review incidents from multiple general practices, have not been found to be effective as recruitment and continued involvement are major problems and significant incentives are required.7–11 Timely feedback regarding incident reports is essential to secure confidence in the process.12 In a broad ranging review of incidents in primary healthcare, there was no mention of an in-house IRC.13 This paper outlines the process for developing an in-house IRC in general practice.

Institution of IRC

Camp Hill Healthcare (CHH) has 17 general practitioners (GPs), five clinical nurses, two community nurses, one diabetes educator, two mental health nurses, two non-dispensing pharmacists, three management staff, two administration staff and 12 reception staff, as well as six visiting allied health professionals.

In December 2010 an IRC was formed. The committee was chaired by a GP and comprised a clinical nurse, a community nurse, a receptionist and an assistant manager. All staff members were advised to continue to report significant medical incidents or patient complaints to the practice manager and principal, and to

their medical insurance agency as necessary. The role and functioning of the new IRC was as follows:

- Staff members were encouraged to report any event that could have led to a problem (not just incidents that did lead to a problem).

- Incident report forms (Appendix A, available online) were made available on the desktop in every doctor’s room, at all reception areas and in the nurses’ room.

- Staff members were encouraged to complete an IRC form, anonymously if they wished, and deliver it in person or via a pigeon hole.

- Management assessed each report and made an immediate response, if needed, recording this response on the form.

- The IRC met monthly to review all incidents and to develop a Near Miss and Adverse Events Register (the Register).

- The IRC meetings were open to all staff and the minutes were accessible to all staff.

- The members of the IRC were considered unavailable for other duties during meetings.

- All incident reports were scanned and filed for future reference.

CHH has kept a record of incidents occurring in the practice since 2004. Incidents include any patient complaints, any clinical accidents and any health and safety issues. All incidents from previous years as well as new incidents were reviewed by the IRC, placed on the Register and graded according to risk. Risk was evaluated as either:

- clinical – risk of a poor outcome for a patient

- business – risk of detriment to the practice reputation

- other – where neither of the above applied.

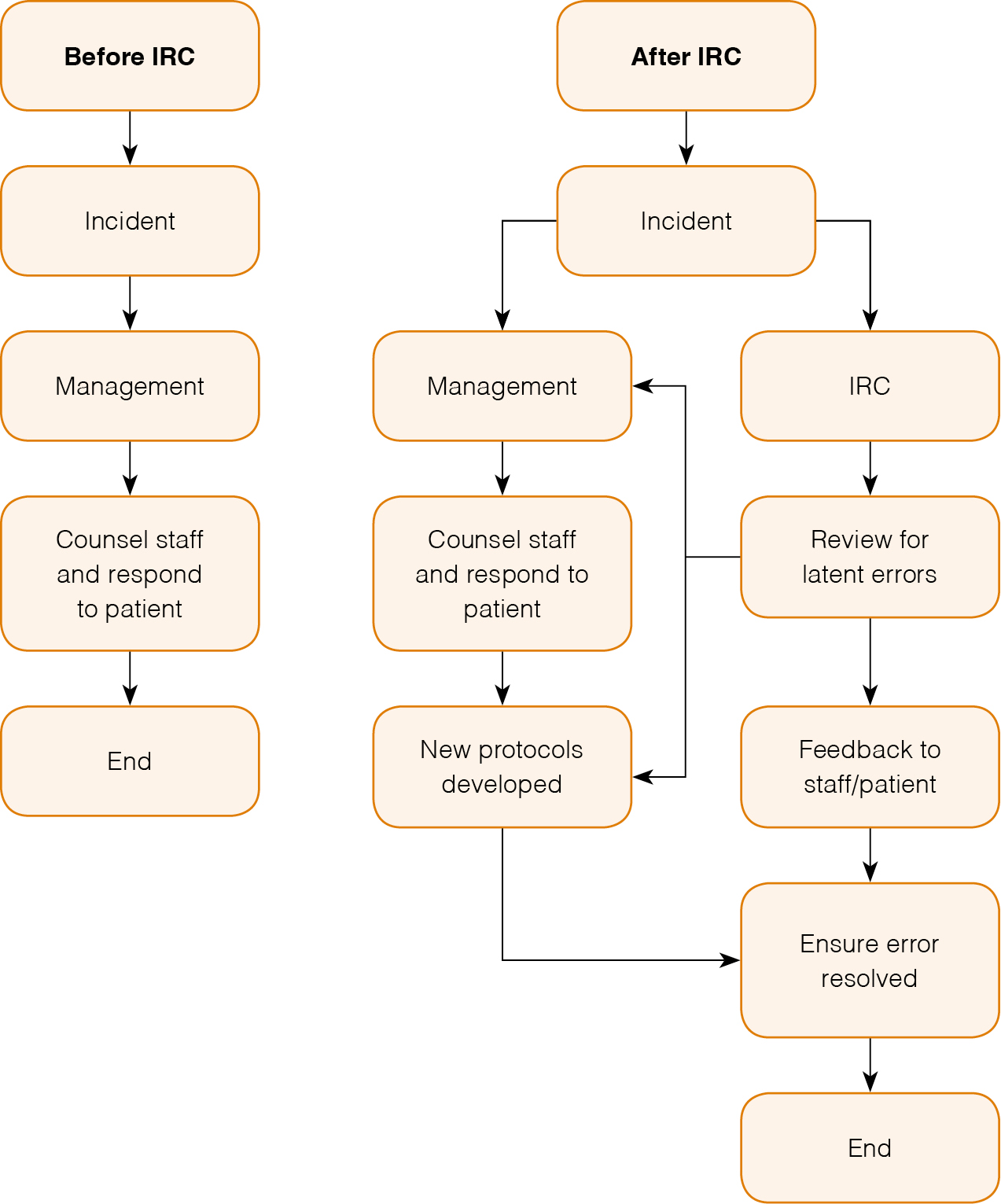

An original graded risk tool was developed (Appendix B, available online). Risk was graded from 1–5 (1, very low; 5, very high risk, requiring urgent action). The chair of the IRC ensured feedback to staff of proposed system changes and, where necessary, notified patients. Figure 1 depicts the way incidents were dealt with before and after instigation of the IRC.

An anonymous, Likert scale questionnaire was distributed to evaluate staff attitudes towards the IRC.

|

| Figure 1. IRC enhances management of incidents |

Results

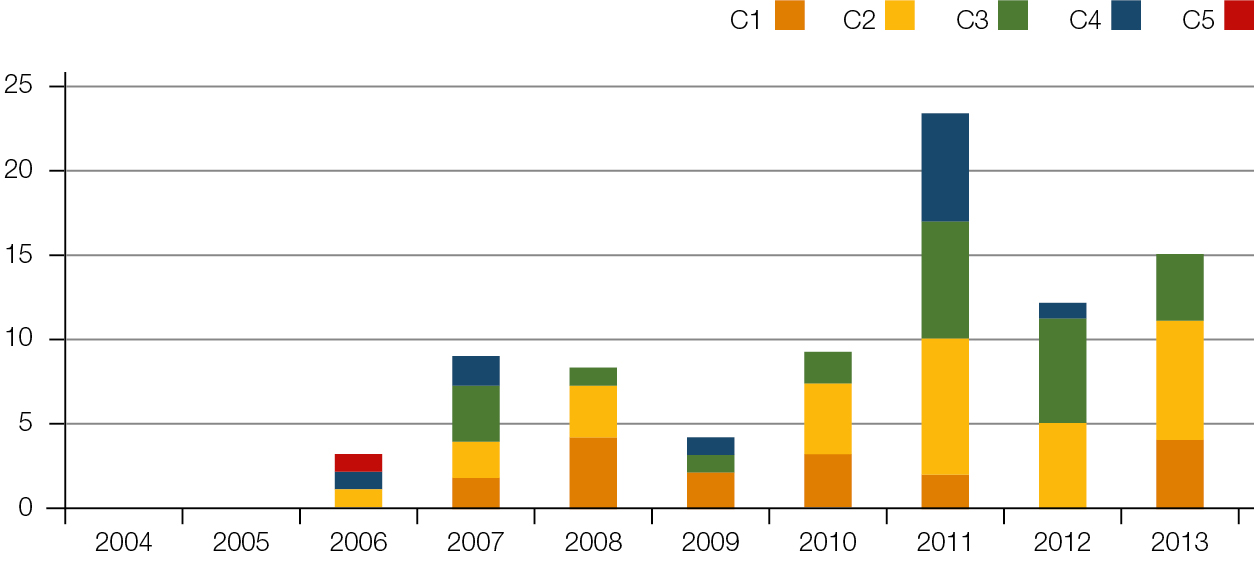

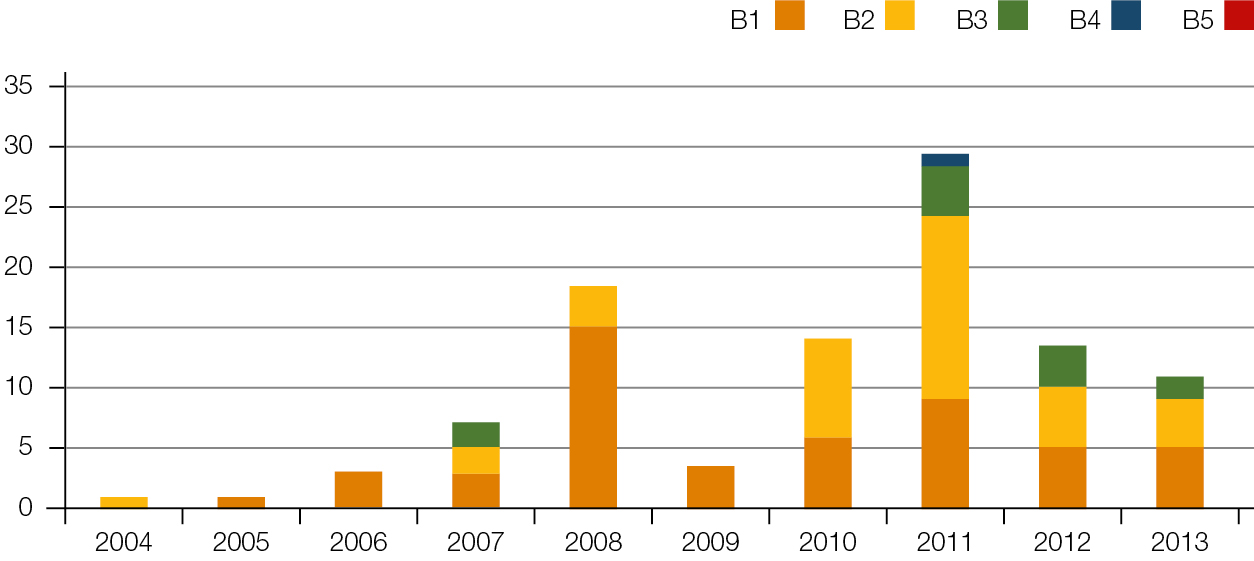

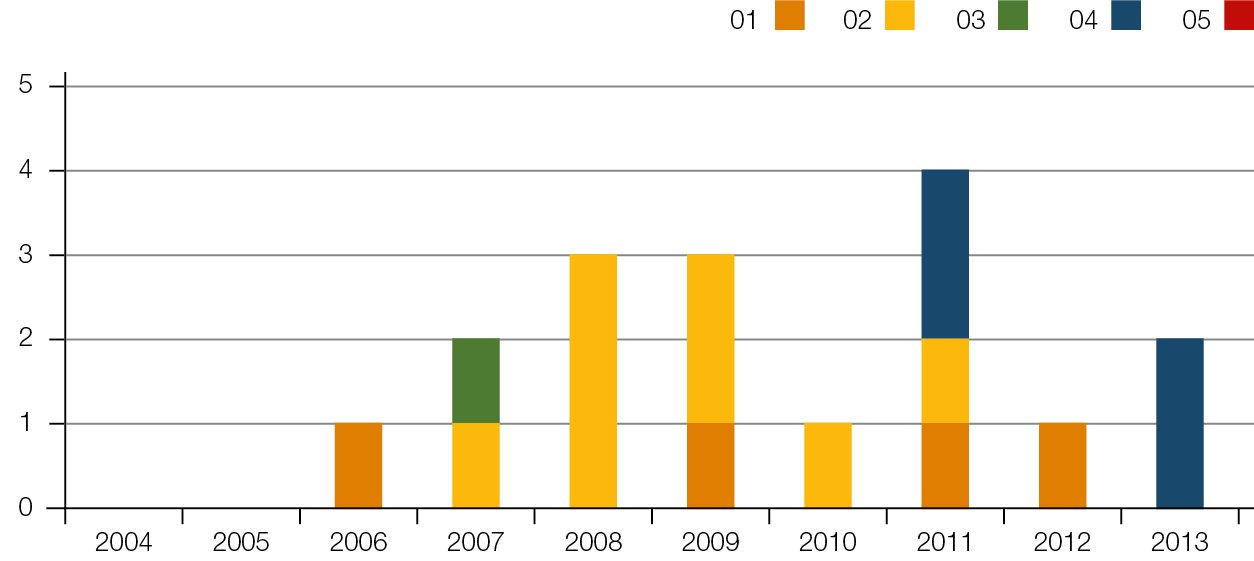

The IRC reviewed 200 incidents. The type, number and grade of incidents reported are shown in Figure 2–4. Changes implemented at CHH as a result of the work of the IRC include:

- protocols for sending billing after excisions to ensure doctor has advised patient of diagnosis

- protocols for urgent assessment of patients in waiting room in the event of reception concerns

- improved design and administration of patient recall system

- improved protocols for checking injections

- improvement in nursing protocols for wound dressings

- layout of equipment in doctors’ rooms checked to ensure disinfectant gels and lubricant gels stored separately

- regular education in use of emergency help button on doctors’ phones

- improved procedures for patient identification to reduce incidence of incorrect filing

- email protocols for improved communication between reception and clinical staff

- incentives to improve attendance at reception staff meetings

- correction of problems with phone diversion to after-hours service

- protocols regarding triaging calls when the doctor requested was not available

- computer software faults detected and corrected

- monitoring of adequacy of reception staffing

- development of a practice social media policy.

The results of the staff satisfaction questionnaire revealed an overwhelmingly positive attitude towards the IRC.

|

| Figure 2. Number of clinical incidents per grade per year |

|

| Figure 3. Number of business incidents per grade per year |

|

| Figure 4. Number of other incidents per grade per year |

Review

There have been many benefits to CHH in implementing the IRC. These include:

- improved support of staff when they maintain practice protocols in the face of adversity

- identification of deficits in practice protocols

- follow-up of all incidents through to resolution

- improved awareness that good communication between different staff groups can reduce risk

- increased team-building, as all elements of the practice have input into the review process in the IRC

- improved education of staff as to the importance of practice protocols

- professional handling of all complaints with documentation, review and feedback provided to the patient and staff, with a view to continual practice improvement.

Discussion

In order to implement a successful IRC all staff must be confident that it is not about apportioning blame but about detecting latent errors and near misses.6 The high satisfaction rate of staff in the IRC attests to its acceptability and this in turn is the most secure way of ensuring that staff will continue to report incidents as they occur.

CHH has always had a structure in place for addressing active errors or violations of practice protocol; the IRC’s role was not to replace these structures but to enhance them.

The ease of having one form for all incidents and one multidisciplinary body reviewing all incidents has been very beneficial. The multidisciplinary nature of the IRC is its strongest asset. Understanding the pressures that other staff members are experiencing informs us greatly on why incidents occur and helps us to devise workable solutions to improve patient care, staff safety and practice reputation.12

Implications for general practice

- An in-house multidisciplinary IRC can reduce risk in general practice.

- The literature indicates incentives are required to encourage an incident reporting culture in general practice.7,8 Making an in-house IRC a requirement for accreditation could address this issue.

- Establishment of an IRC at CHH, as outlined in this paper, can be used as a template for general practices to establish their own IRC.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Chris Freeman PhD BPharm, GDipClinPharm AACPA, non-dispensing pharmacist, Camp Hill Healthcare, for his advice and insights in preparing this paper.