General practice training in Australia resembles an enhanced apprenticeship model where vocational trainees (registrars) practice ‘independently’, but must have supervision from accredited supervisors.1–4 Supervision typically occurs as scheduled teaching time, or as shorter, impromptu interactions between supervisor and registrar outside this time (called ad hoc encounters). Ad hoc encounters generally arise from a consultation with a patient, where the registrar has judged that the situation exceeds their ability to manage independently.5

Most literature focusing on general clinical supervision emphasises provision of trainee education and maintenance of patient safety,3,6,7 along with identifying the traits of a good supervisor.3,8 With respect to ad hoc supervision in general practice, an unpublished survey of general practice training in southern Victoria found registrars believed the encounters provided the most beneficial education,9 emphasising the importance of practice-based learning.10 However, other research tends to focus on respondents’ reports of events during these ad hoc encounters. There is little published literature exploring perceptions of ad hoc encounters by the key players within general practices.

The data reported in this paper were collected as part of a larger project investigating ad hoc encounters between supervisors and registrars. For this larger project, the researchers collected:

- interviews with supervisors, registrars and practice managers for the context of ad hoc encounters

- real-time audio recordings of ad hoc encounters between supervisors and registrars

- audio-recorded reflections by supervisors and registrars on the supervision encounters.

This paper presents ancillary findings from individual interviews with supervisors, registrars and practice managers in regional Victoria, reporting their perceptions of ad hoc encounters in general practice training.

Methods

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted as part of a larger exploratory case-study research design,12 where the overarching question was ‘What happens during ad hoc supervision of general practice registrars?’ Findings from this study, based on analysis of real-time audio recordings of ad hoc encounters, have been reported elsewhere.11

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of participants, and interview length

|

|

Supervisors

|

Gender

|

Age

(years)

|

Years

as GP

|

Years as GP supervisor

|

Australian- trained

|

IMG

|

Length of interview (minutes)

|

|---|

|

Supervisor A

|

Male

|

44

|

14

|

9

|

|

✓

|

40

|

|

Supervisor B

|

Male

|

37

|

10

|

10

|

✓

|

|

56

|

|

Supervisor C

|

Male

|

61

|

32

|

20

|

|

✓

|

27

|

|

Supervisor D

|

Male

|

51

|

20

|

10

|

✓

|

|

35

|

|

Supervisor E

|

Male

|

55

|

25

|

18

|

|

✓

|

37

|

|

Registrars

|

Gender

|

Age

(years)

|

|

Stage

of training

|

Australian- trained

|

IMG

|

Length of interview (minutes)

|

|---|

|

Registrar A

|

Female

|

30

|

|

GPT2

(7 months)

|

✓

|

|

46

|

|

Registrar B

|

Female

|

28

|

|

GPT1

(3 months)

|

✓

|

|

39

|

|

Registrar C

|

Female

|

46

|

|

GPT2

(9 months)

|

|

✓

|

31

|

|

Registrar D

|

Female

|

44

|

|

GPT1

(3 months)

|

|

✓

|

48

|

|

Registrar E

|

Female

|

43

|

|

GPT2

(9 months)

|

✓

|

|

38

|

|

Practice manager

(PM)

|

Gender

|

|

|

|

|

|

Length of interview (minutes)

|

|---|

|

PM A

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

12

|

|

PM B

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

21

|

|

PM C

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

19

|

|

PM D

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

24

|

|

PM E

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

13

|

|

IMG, international medical graduate

|

Participants

The participants were five supervisors, five registrars and five practice managers from separate practices in regional Victoria. Demographic data are shown in Table 1.

As a purposive sample, our participants reflected Miles and Huberman’s ‘convenience’, ‘criterion’ and ‘typical’ sampling categories.13 ‘Typical’ cases represent what is ‘normal’ or ‘average’. Participants were recruited from one regional training provider and registrars were in their first year of training. We believed the participants were ‘ordinary’ supervisors, registrars and practice managers, and that their views reflected the typical views of these stakeholders.

Data collection

An interview protocol was developed to elicit participants’ responses regarding teaching and learning, and the context of supervision, which included specific questions on ad hoc encounters. Box 1 provides an example of the protocol used to interview registrars. During September 2013, JM conducted interviews with all participants. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Box 1. Example interview protocol: General practice registrars

|

|

Ad hoc supervision encounters

- Do you see ad hoc encounters as important? Useful? Why or why not?

- As opportunities for learning, how do ad hoc encounters differ from formal education sessions?

- What do you want to get out of them?

- In what circumstances have you asked for help? Are you ever reluctant to ask for help?

- How do you feel about ad hoc encounters?

- Examples of exemplary ad hoc encounters? Encounters that did not go well?

- How are ad hoc examples followed up, if at all?

Demographic details

|

Data analysis

Interview data were analysed using template analysis14 in which a priori codes were created, and which allows for the development of new coding categories during analysis. TC and JM developed the initial template using the QSR NVivo 10 qualitative software.15 Regular team meetings allowed for peer debriefing,16 where JB and DN provided an ‘external check’ on the analysis.

Ethics

Approval for the study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: CF13/1225-2013000592).

Results

The participants’ perspectives on ad hoc supervision are presented in five categories from the final template: immediacy, safety, education opportunities, professional identity and supervisor stress.

Immediacy

During ad hoc encounters, the registrar receives an immediate response to their question from their supervisor. This immediacy was highly valued by supervisors, registrars and practice managers.

Ad hoc [encounters] just tick a whole lot of boxes really … the patient has evidently highlighted a gap in the registrar’s knowledge or management, so their deficiency is made known to them, they’ve become aware of it, they’ve sought assistance, you’ve provided that assistance there and then. – Supervisor D

As a registrar, [ad hoc encounters] are really, really, really important. If I only could talk to [Supervisor E] on my one [or] two hours on a Tuesday, and could not talk to him in between, that would just be horrible. – Registrar E

[They’re] extremely helpful to the registrar because the majority of the time, it’s discussing someone that you’re caring for right at that moment and getting some backup for that.

– Practice Manager D

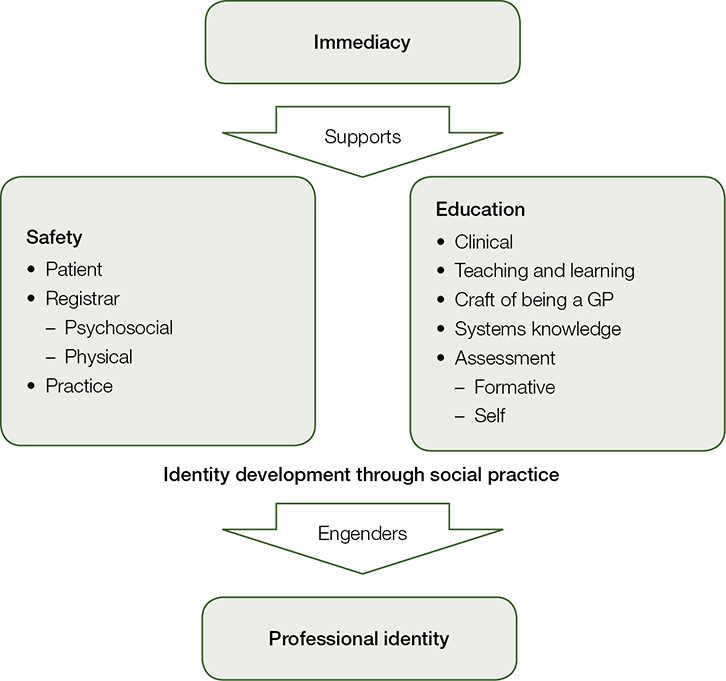

The immediacy of ad hoc encounters provided the information that the registrar needed at that moment to progress patient care. This way, immediacy supported safety and education.

Safety

Three aspects of safety were identified by participants as important and valuable attributes of ad hoc encounters: patient, registrar and practice safety.

Patient safety

All respondents considered that ad hoc encounters played a pivotal role in ensuring patients received safe, quality care.

I would say the most important reason for [ad hoc encounters] is patient safety. – Registrar B

Rather than make mistakes, they’re encouraged to talk with [the supervisor] and get it right. Obviously risk-wise, we want … them to be making good decisions regarding their patient care, and if that means talking to someone, then that’s all encouraged.

– Practice Manager E

A lack of requests for immediate support might indicate that a registrar was not practising safely, as suggested by this supervisor:

If they never ring me, I’m really quite worried because there’s nobody in the world who can be sitting in and solving all the problems, so that will make me more likely to look at their case notes and check that they’re doing the right sort of job. – Supervisor E

Registrar safety

Registrar safety had two components: psychosocial and physical safety.

Psychosocial safety

Ad hoc encounters were considered important from the perspectives of the registrars’ psychosocial safety – that is, their emotional and psychological wellbeing and feelings of belonging to their particular ‘community of practice’.17 Registrars in general practice usually consult ‘independently’ in their own room. At times, they might have experienced feelings of isolation,18 and felt out of their depth, especially at the start of their training.

It’s just a horrible feeling being literally in a room with someone and one, not knowing what their problem is, and two, not knowing how to fix it. Like you see a rash, and you’re not sure what it is and you really don’t know what to do with it. Obviously that improves as you get more experience, but the first few months every single day, you see something that you really have no idea about and it really does knock your confidence. It’s pretty exhausting. – Registrar E

Access to immediate advice through ad hoc supervision encounters was important to ensure questions could be addressed and that registrars felt supported and confident. Some practices made particular arrangements to enhance registrars’ access to support.

We place our registrar in the building close or next door to the supervisor’s so that that encourages contact, corridor discussions, et cetera, rather than discouraging it. – Practice Manager E

Physical safety

At times, a registrar could encounter a difficult patient and a quick response from their supervisor might be necessary for the registrar’s physical safety. Registrars discussed feeling the need for interventions by their supervisors when patients made a request that they were unwilling to meet (eg requests for drugs of addiction or for false certification). Refusal of these requests might have resulted in threatening behaviour by the patient.

Occasionally [the reason for the ad hoc encounter is] physical safety, if they’ve got a really dreadful person in the room with them. – Supervisor E

Practice safety

Ad hoc encounters were considered important to the safety of the practice. General practices are private businesses that have financial and reputational considerations.19 Negative outcomes from a consultation with a registrar may reflect badly on the practice as a whole.20 While participants commented that ad hoc supervision of registrars increased the workload of supervisors, it was perceived that ad hoc encounters could assist with the flow of patient appointments as registrars’ queries were dealt with quickly. Thus, ad hoc supervision provides the practice with an important opportunity to maintain its professional reputation.

Overall there’s kind of a corporate confidence [patients] have, you know. They’re going to the [practice name’s] doctor and they’ll expect certain outcomes regardless of whether [they see a registrar]. – Supervisor B

Education

Ad hoc encounters were perceived as being important in the provision of different teaching and learning opportunities, and in matters of assessment.

Teaching and learning opportunities

An important feature of ad hoc encounters was the teaching and learning opportunities these provided. Supervisors commented that ad hoc encounters provided ‘teachable moments’ from a registrar’s immediate need for help. Ad hoc encounters were valued by registrars and provided the chance to tap into the experience of their supervisors’ knowledge and skills.

[Ad hoc encounters are] certainly very good for teaching. They’re certainly rated very highly by all the learners. I would think there’s no doubt that they’re very good for teaching. – Supervisor D

Registrars’ responses focused on the learning opportunities of ad hoc encounters.

I think that [ad hoc encounters are] the best learning opportunity because you learn more when you have a question which is bothering you and you’re looking for the answer. You tend to remember this much better than when you sit down and read or talk with the supervisor. – Registrar D

We identified three categories of teaching and learning opportunities: clinical learning, the craft of being a general practitioner (GP), and systems knowledge.

Clinical learning

Ad hoc encounters provided an opportunity for registrars to learn clinical issues that arise during their consultations with patients.

For clinical things I definitely learn better through experience. So I could have 10,000 tutorials on rashes and I still wouldn’t understand them, but then I’ll see a particular rash [during an ad hoc encounter] and I won’t forget it. – Registrar A

The craft of being a GP

Ad hoc encounters were viewed as important opportunities for registrars to learn the craft of being a GP. The encounters allowed the registrar to learn public, interpersonal and intrapersonal professionalism,21 which encompasses skills such as communication, relationship building, knowledge of social issues and the management of patients’ expectations. In this example, the registrar reported how the supervisor could act as a role model:

I think being able to see how [supervisors] approach a patient in a real setting … When they examine, what sort of questions they ask that you missed [laughs]. And how they reassure the patient too and give them feedback or information on whatever it is they’ve got. I think it’s beneficial seeing that. You wouldn’t see that in the planned teaching because it’s not with a patient. – Registrar B

Systems knowledge

How to use and navigate through the systems and bureaucratic processes of working as a GP was an area of learning supported by ad hoc encounters.

[Ad hoc encounters] might be for issues around the actual medical side of things – other times, they might be around computer issues, like, ‘How do I print up this or that?’ And sometimes, it’s around more of the bureaucratic systems, where [the registrar] is not exactly sure which form to use, or how exactly to go about a procedure. It might be around WorkCover, TAC [Transport Accident Commission], things like that. – Practice Manager C

Assessment

Ad hoc encounters were perceived as providing the opportunity for two types of assessment: formative assessment by the supervisor, and self-assessment by the registrar.

Formative assessment

Ad hoc encounters provide an opportunity for supervisors to assess their registrar’s performance.

Well, it helps you with assessment in a lot of ways. One is at what point have they called for help; how well have they thought it through before they’ve rung? How good are they at assimilating the information they want to give you? If they ring and say, ‘This guy’s got a sore toe and what do I do?’, it’s obviously very different to ringing and saying, ‘Look there’s a man here and his right toe is inflamed, there’s some redness in this area and I think I should start an antibiotic and I’m thinking of Keflex, but do you think I should start Diclocil?’ Massive difference in what I’m going to think of those two registrars. – Supervisor D

Self-assessment

Registrars were able to use their own performance in ad hoc encounters to monitor their training progress.

They’re one of the tools of assessment, of how I’m progressing. What I mean is that when I become briefer and clearer about describing what’s been happening, that shows that I’m improving, rather than the supervisor trying to pull all the strings together. When I do it myself, that means I’m in control and I’m improving. – Registrar D

Professional identity of the registrar

Ad hoc encounters were seen as important for the development of registrars’ professional identity: their professional self-concept based on the attitudes and values that inform their practice.22 The response by a supervisor to an ad hoc query could have an impact on how the registrar perceived themselves as a GP.

[Ad hoc encounters] develop confidence because sometimes I’ve been told [by the supervisor] it’s all good and they cannot add anything and it means that I have … exhausted all the options. – Registrar D

Ad hoc encounters were an opportunity for the registrar and supervisor to engage in what Wenger calls ‘social practice’.17 This is a key process where registrars learn to become GPs, and highlights the link between social practice and identity formation (Figure 1). Through social practice, registrars learned that even experienced supervisors encounter uncertainty and that it was a legitimate activity to ask a colleague for their opinion. An important part of developing the identity of a competent GP was being able to be ‘satisfied with uncertainty’.23

And I realised that [my supervisor] doesn’t know either, but he is able to convey this to the patient and say, ‘I’m not sure exactly what this is, but we are going to do this and this test and find out’. And I found that actually people with 30, 40 years’ experience, they can communicate this to the patient and the patient is not saying, ‘What doctor is that? He doesn’t know what he is doing’. – Registrar D

Stress for supervisors

Although the participants were overwhelmingly positive in their perceptions of ad hoc encounters, some responded that ad hoc encounters could place extra stress on supervisors. It was acknowledged that this was something that was expected when there are trainees with different levels of confidence and competence in the practice.

It probably places more strain on the supervisors … if they’ve had a complicated case or something has occurred and they’re trying to catch up and then the ad hoc encounter comes up. I think it’s just something that just comes along with GPs who don’t have the same experience as more experienced GPs. I think that it is probably something that you just have to accept if you’re a training practice, that’s going to occur. – Practice Manager C

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study reporting on the perceptions of ad hoc supervisory encounters within general practice from the perspectives of supervisors, registrars and practice managers. A significant aspect of this study’s contribution is that it provides empirical data to complement general practitioners’ previously unpublished experiential knowledge regarding ad hoc encounters. Participants articulated that ad hoc encounters played a central role in ensuring the safety of participants and that registrars are expected at times to request supervision. Other research findings highlighted registrars’ obligations to request supervisory assistance and the potentially dangerous risks to patients of failing to do so.24 In one study of general practice registrars, a small but significant number of critical incidents occurred because trainees felt reluctant to ask for help. The registrars feared that they would look stupid or lose credibility with patients or supervisors.5

Ad hoc encounters are also viewed as important opportunities for registrar education, which echoes the discourse in the broad clinical supervision research and policy literature.6,7 More specifically, these are valued for their relevance and applicability.25 The findings also supported registrars’ claims9 that ad hoc supervision is extremely beneficial for their education.

Ad hoc encounters allow the registrar to engage with the patient and supervisor together. The immediacy of ad hoc encounters supports patient safety and enables these to be powerful learning experiences (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. How ad hoc encounters support safety, education and professional identity |

Our findings highlight that safety in ad hoc supervision is multifaceted, extending to patients, registrars and the practice. Ad hoc encounters are important for the registrar to learn clinical skills, the craft of being a GP, and systems knowledge, and to develop their professional identity. These provide an opportunity for assessment arising from supervisors’ observations and registrars’ self-assessments.

This study underlines that ad hoc supervision encounters are important in the training of general practice registrars and are highly valued by the three participant groups: supervisors, registrars and practice managers. We posit that effective ad hoc supervision requires expertise and time. Supervisors need training and adequate resourcing. Time taken by supervisors to engage in ad hoc supervision of registrars may mean that they run late for, or lose time with, their own patients; pressures that are not conducive to maximising the potential value of ad hoc encounters. While safety is the cornerstone of ad hoc encounters,4 the educational value of ad hoc encounters can be secondary. Readers are referred to the aforementioned research report for further discussion of how greater use can be made of ad hoc encounters as teaching and learning opportunities. We recommend that provision of ad hoc supervision be prioritised in the training of GP supervisors and that resources be provided to enable them to allocate the time to deliver effective ad hoc supervision.

Study limitations

Our study focused on supervisors’, registrars’ and practice managers’ perceptions of ad hoc encounters in general practice training. This was part of a small exploratory study in rural Victoria. Participants were purposively selected and willing; therefore, findings may be limited in their generalisability. We did not have input from patients, who are likely to contribute another perspective on the value of ad hoc supervision and should be considered for inclusion in future studies.

Implications for general practice

Ad hoc supervision encounters in general practice:

- are important for the safety of patients, registrars and the practice

- are valued for the learning opportunities they provide to registrars

- engender the development of registrars’ professional identity

- require adequate resourcing.

Authors

Jane Morrison MA, Research Officer, Southern GP Training, Warrnambool, VIC; Clinical Associate Lecturer, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, VIC. jane.morrison@sgpt.com.au

Tim Clement PhD, Quality Assurance and Education Development Advisor, Southern GP Training, Warrnambool, VIC; Clinical Associate Lecturer, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, VIC

Debra Nestel PhD, Professor of Simulation Education in Healthcare, School of Rural Health, HealthPEER, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, VIC

James Brown MBBS, MFM (Clin), Director of Training, Southern GP Training, Churchill, VIC; Clinical Associate Lecturer, School of Rural Health, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, VIC

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge General Practice Education and Training (GPET) for its funding of this study through the GPET Education Integration Program (II). We also acknowledge and thank the registrars, supervisors and practice managers who participated in this project.