Behaviour problems are common

Parents are increasingly bringing their children to doctors, with concerns about their behaviour and development.1,2 In fact, every parent finds their children difficult to manage from time to time. Usually, these behaviours are statistically normal and part of normal developmental variation (Table 1). Occasionally, they represent a more serious underlying disorder, such as developmental delay, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), attachment disorder, anxiety disorder or adjustment disorder to environmental stresses or trauma. Asking questions about developmental milestones, family history, parent–child emotional attachment, parental emotional state, and the severity and context of specific behaviours will shed further light on environmental and biological contributions to the behavioural and/or developmental variation. It is always worth asking: ‘Why is this child behaving in this way, in this situation, at this time?’

Most severe behaviour in the preschool period usually fades progressively with time and does not carry long-term negative prognostic significance. The Montreal longitudinal study that followed 1000 boys from birth to age 15 years found that aggression peaked at three to four years of age.3 If those aged three years were the size of adults, most of them would be in jail!

Table 1. What is normal

|

|

Behaviour

|

Age 2

%

|

Age 3

%

|

Age 4

%

|

|

Eats too little

|

50

|

26

|

37

|

|

Resists going to bed

|

70

|

46

|

56

|

|

Night-time waking

|

52

|

52

|

56

|

|

Wets bed at night

|

82

|

49

|

26

|

|

Hits others or takes things

|

68

|

52

|

46

|

|

Stubborn

|

95

|

92

|

85

|

|

Disobedient

|

82

|

76

|

78

|

|

Constantly seeks attention

|

94

|

48

|

42

|

|

Whines and nags

|

83

|

65

|

85

|

|

Active, hardly ever still

|

100

|

48

|

40

|

Principles of management

Box 1. Principles of behaviour management

|

|

Stabilise routines

Provide special time

Praise and reward positive behaviours

Prioritise difficult behaviours

Ignore minor difficult behaviours

Immediate consequences for major difficult behaviours

Minimise talking at time of misbehaviour

Debrief later when things are calm

|

The principles of behaviour management for preschoolers who are difficult are listed in Box 1. Young children lack internal control, and are therefore more dependent on a clear, calm and firm behavioural scaffolding to help them with emotional containment. Walking parents through these principles step by step can be very valuable. Irrespective of the origin, severity and complexity of the difficult behaviour, high-quality handling remains an essential, if not necessarily a total, fix for their problems. General practitioners (GPs) are in an excellent position to help parents with behaviour management of their children and, just as importantly, to also provide the emotional support that frazzled parents almost always need. Some parents will struggle to implement even the simplest strategies because of powerful subconscious influences from how they were parented as children and in light of their own mental state. This work is therefore best done in brief chunks, one step at a time, over several short sessions. This also helps with the parents’ emotional containment.

Praise and rewards

Parents should be encouraged to go out of their way to ‘catch the child being good’. Praise should involve eye contact, getting physically close, making praise immediate, and praising the behaviour and not the child. ‘Nice sharing your toys with your sister’ is more effective than ‘Good boy, Darren’. Similarly, ‘You are playing very gently, Candice. Well done’ is superior to ‘Good job, Candice’. Good behaviour does not impose itself on parental consciousness as much as bad behaviour, and is easy to ignore.

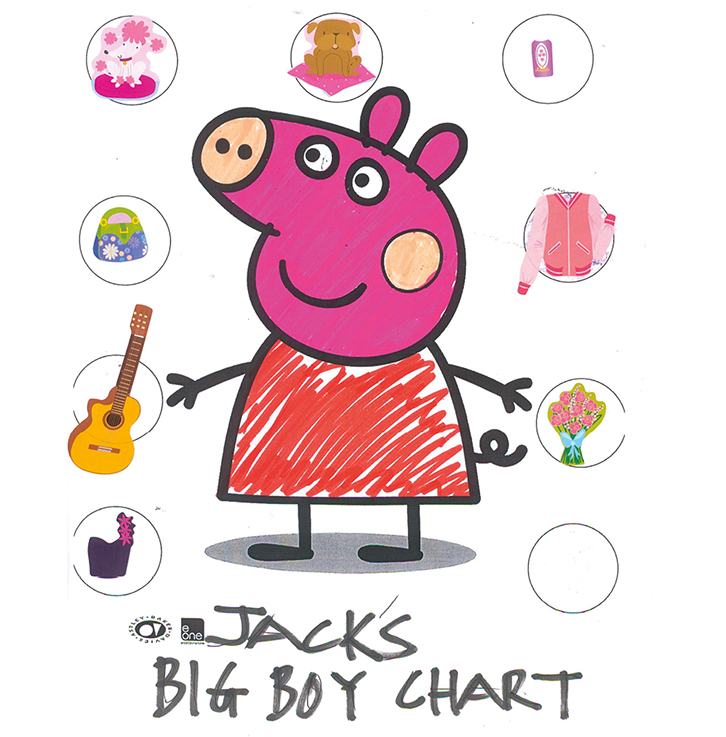

Reward charts in various forms are valuable for children two to eight or nine years of age. These are a concrete way of acknowledging positive behaviours and providing a balance between positive and negative attention. Stickers or stamps on the back of the hand, sticker charts culminating in lucky dips, points charts, or random rewards used in short, sharp bursts can be used depending on the child’s age and interest. Points or stickers for specific positive behaviours need to be awarded at least three or four times per day, and the chart or tally completed after several days. Then, have a break for one week before running another chart for several days, culminating in another reward. Spacing out charts wider and wider, and finishing them up quickly, is crucial for maintaining interest and novelty. Any chart running for more than one week is too long and usually just fizzles out without effect.

If children get bored with stickers or points, then use various tokens (eg poker chips, twenty cent pieces, marbles in a jar, footy cards or other random knick-knacks) in short, sharp bursts in a similar way.

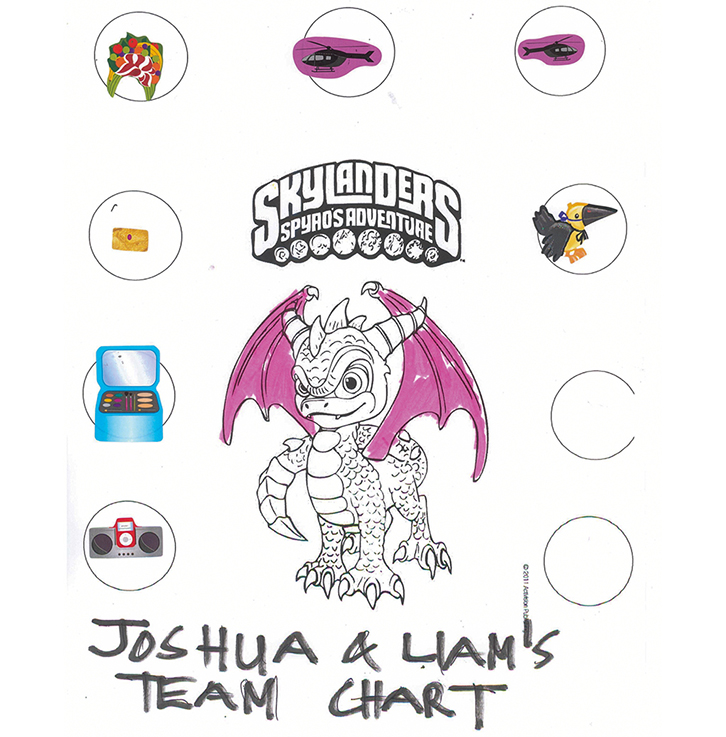

If points, stickers or tokens are awarded for good behaviour, it is crucial that they should not be withdrawn for negative behaviour. Charts can be generic, for any positive behaviour (Figure 1), or for more specific behaviour (Figure 2). If there are siblings closely spaced in age, team charts are preferred over separate charts for each child (Figure 3).

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Reward chart for any good behaviour |

Figure 2. Reward chart for specific behaviour |

Figure 3. Sharing a reward chart with siblings |

Prioritising difficult behaviours

Negative behaviours need to be prioritised. The GP can help parents to make a list of behaviours that are best ignored, where attention needs to be withdrawn (low-priority behaviours), and behaviours that are more serious and require a disciplinary consequence (high-priority behaviours). The number one mistake most parents make with young children is doing too much talking at the time of misbehaviour. When children are upset, they not amenable to reasoning, which should be saved for later when things are calm.

Withdrawing attention

Ignoring low-priority behaviours (eg whining, whinging, tantrums, noisiness, hyperactivity and even swearing) is not saying these behaviours are okay, but is about withdrawing the attention the child may have previously received for engaging in these behaviours. Ignoring should involve breaking eye contact, walking away, going into another room, and paying attention and praising the child the moment the misbehaviour stops (eg ‘Nice calming down, Bailey’). This last step is often forgotten.

Providing consequences

For high-priority behaviours, such as hitting, hurting, defiance, dangerous behaviours or deliberately breaking things, disciplinary consequences need to be applied. Again, minimising talking at the time of misbehaviour is vital (debriefing can be undertaken later). Preferable disciplinary consequences are timeout alone for children aged 18 months to four years, timeout followed by withdrawal of privileges for children aged four to eight years, and withdrawal of privileges alone for those over eight years of age. Contracting and dispute mediation with their parents is preferred for older children and adolescents, and is beyond the scope of this paper.

Timeout is a symbolic act for thinking time and is not about making the child suffer. Sometimes, children will be distressed when placed in timeout, sometimes they will not. This does not matter. Timeout can be used in a playpen, sitting on a chair, in the bedroom, on a back step or outside the back door, depending on the child’s age and behaviour. In general, when at home, the author’s preference is timeout in the bedroom holding the door for one to two minutes only. Outside the home the preference is timeout standing aside holding the parent’s hand up against a wall in another room, against a shop window or standing next to a tree at the park, for 30 seconds to one minute only. Traditionally, one minute of timeout per year of age has been recommended but the child should not be removed from timeout until they are calm and quiet. However, the author’s preference is to finish timeout as soon as the time is up, irrespective of whether the child is calm or not. They can then be placed back in timeout for a second session if serious behaviour recurs or continues.

Parents should act immediately and impose timeout as soon as the misbehaviour occurs, not after five or 10 warnings or an escalating series of threats. One warning phrased as a ‘3, 2, 1’ countdown is appropriate for defiance. When the child is allowed out of timeout, they should be praised as soon as they are calm. If they continue to ‘carry on’, they should be ignored until the behaviour settles. If serious behaviour recurs, they should be placed back in timeout for a second session.

For children over the age of four years, short-term withdrawal of privileges should occur following timeout, or as a stand-alone consequence for children over eight years of age. Parents should draw up a list of six or eight privileges they can withdraw, and rotate through these rather than always withdrawing the child’s most treasured possession. Withdrawal of privileges may involve loss of a toy, withdrawal of screen time, missing out on a treat, or being sent to bed early. Just as with timeout, privileges should be withdrawn immediately after the serious behaviour occurs or, at most, after a single warning and ‘3, 2, 1’ countdown. Withdrawal of the privilege for two to 12 hours, usually until the next natural break, such as lunchtime, dinnertime, or until tomorrow morning, is sufficient. In the author’s personal opinion, extended withdrawal of privileges for 24 hours or longer is usually less effective. Removing a child’s iPad for one month is unlikely to be followed through; even if it is, this will not be any more effective than removing the iPad for 12 hours. Consequences are about symbolism, not about making the child suffer. Less is more. Similarly, delaying consequences is not advocated. ‘You are not going to Sally’s party next Thursday week’ will not work even if it is followed through.

Conclusions

The principles of behaviour management can be applied to a range of under-controlled behaviours, as well as to other challenges confronting parents, including problems around children’s toileting, eating, feeding and sleeping (Box 1). The principles are not a substitute for parent–child relationship therapies, counselling or cognitive behavioural therapy-based (CBT) self-control work in older children. However, love, affection, positive attention, stabilising routines, and boundary and limit setting are essential components of good parenting. A meta-analytic review of parent training program effectiveness indicated that components consistently associated with larger effects included increasing positive parent–child interaction and emotional communication skills, teaching parents to use timeout, parenting consistency, and requiring parents to practise new skills with their children during parent training sessions.4 GPs have a role to play in implementing some of these components with parents in a step-wise way, aided by excellent online resources such as the Raising Children Network compiled specifically for Australian families.5

Author

Rick Jarman MBBS, FRACP, Senior staff specialist, Centre for Community Child Health and Department of General Medicine, Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Vic; Founding Director, Melbourne Developmental and Behavioural Paediatrics, Donvale, Vic; Partner, Melbourne Paediatric Specialists, Parkville, Vic. rick.jarman@mdbp.com.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.