Ageing population trends create a strong clinical and fiscal imperative for healthcare systems of developed nations to develop sustainable and safe models of care that reduce dependence on emergency and inpatient hospital services. People living in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) present to emergency departments (EDs) at rates of 0.1–1.5 transfers per RACF bed/year,1 and 40–60% of these presentations are admitted to hospital.2,3 Although EDs are specialised in delivering acute care to the critically ill and injured, current models of ED care may not optimally meet the needs of frail older patients in RACFs.4,5 Patients (or their families) express a preference to receive (or have their relatives receive) treatment within their home environment.6 Studies conducted in Australia and overseas suggest that older persons treated in such settings are less likely to suffer iatrogenic complications commonly incurred during hospitalisation, including confusion, urinary complications, constipation, faecal incontinence, pressure areas and medication errors.1,7–9 Compared with older persons in general, residents of aged care facilities have longer lengths of stay in the ED and inpatient settings, and higher rates of re-presentation to ED and re-admission to hospital.10 The 2011 Productivity Commission inquiry into caring for older Australians identified people in RACFs as being marginalised in terms of access to and quality of appropriate medical care.11 It was identified that continuity of care for RACF residents with acute healthcare needs and access to information of available services to fulfill their care needs were suboptimal.

Alternative models of care are required that substitute, whenever clinically appropriate and in keeping with resident wishes, outreach or in-home care for inpatient hospital care of people in RACFs. In addition to providing care in a more suitable environment preferred by patients and family, hospital substitutive care also has the potential to achieve several hospital system efficiencies. It minimises costs by providing equivalent care in a lower cost environment,12 reduces in-hospital stays13 and avoids inappropriate use of ambulance transfers to ED.14 Finally, it reduces ED overcrowding, resulting in reduced waiting times and improved ability to meet National Emergency Access Targets.15 The purpose of this article is to describe a unique multimodal program that focuses on maximising quality of care for residents of RACFs with acute healthcare needs, reducing the need for inpatient care as much as possible, and optimising the use of existing community and hospital resources.

Setting

South-east Queensland is Australia’s fastest growing metropolitan region. The population is expected to increase by 30% by 2025, and the 70 years-plus population is expected to grow by 224%.16 The Metro South Hospital and Health Service (MSHHS) services a population of more than 1 million over a 3856 square km area and comprises a 640-bed tertiary hospital and three secondary hospitals with a total of over 710 beds, each having an ED. Within the MSHHS catchment area, there are 84 RACFs with over 7200 beds.

Designing a new model of care

The Comprehensive Aged Residents Emergency and Partners in Assessment, Care and Treatment (CARE-PACT) program is a hospital substitutive care-and-demand management project that was established in early 2014 to better meet the needs of RACF patients in the MSHHS district. The Health Innovation Fund of Queensland Health is funding it for 2 years with a grant of

$3.71 million.

In designing CARE-PACT, note was taken of the successes of earlier models of care developed for the RACF population, which have variously encompassed hospital in the nursing home models,1,17,18 nurse practitioner or nurse-led models,1,19,20 disease-specific clinical pathways1,21 and programs to improve rates of advance care planning in facilities.1,22 However, CARE-PACT also sought to overcome the limitations of some prior models of care for the management of acute health needs of this population. These include poor clarity of clinical governance; limited referral sources; lack of adoption of innovations to increase capacity of services, such as tele-health and nurse practitioners; failure to address the lack of knowledge and under-utilisation of existing community services; lack of an outreach ED assessment service that avoids the need for presentation to hospital in order to access the acute care substitution service; and sole focus on service delivery with failure to provide education and skills sharing that would avoid ongoing dependency on substitutive care services.

Model of care

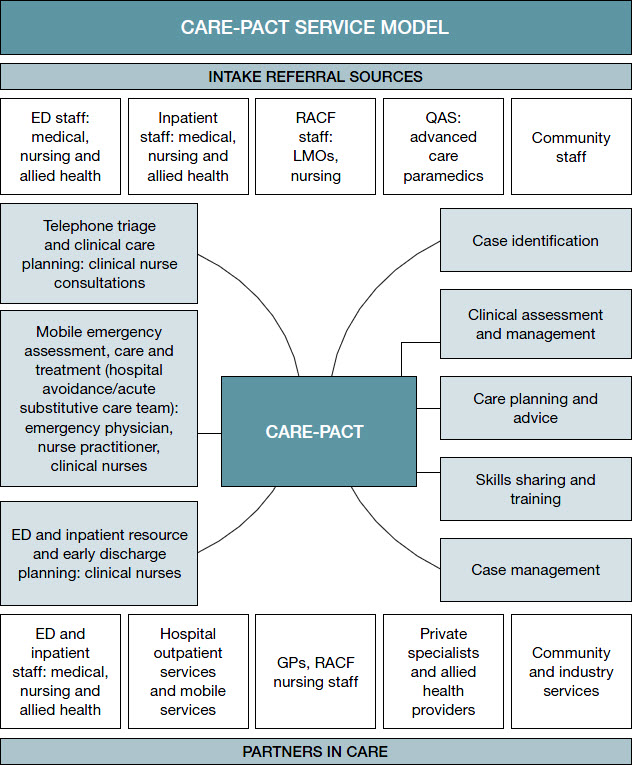

|

Figure 1. CARE-PACT service model

ED, emergency department; LMOs, local medical officer; QAS, Queensland Ambulance Service |

The CARE-PACT model of care, comprising hospital-based and mobile resources, is depicted in Figure 1. Clinical governance for all mobile activity is held by the emergency physician clinical lead, who is accountable to the MSHHS clinical stream lead for medicine and chronic diseases. CARE-PACT has a consultative role for hospital-based activity; clinical governance is retained by treating teams. CARE-PACT services the EDs of the four hospitals within the district and aims to:

- Identify the most appropriate management resource for residents with acute healthcare needs, where these exceed the capacity of the general practitioner (GP) and RACF staff to manage independently of the hospital sector.

- Improve continuity of care and achieve more seamless transition between care settings by developing interagency partnerships and collaborative care planning.

- Improve responsiveness to individual needs of residents, resulting in increased options for care and more selective use of inpatient care.

- Facilitate education and skills sharing across the care continuum involving GPs, RACF and hospital staff in a collaborative effort to provide responsive, evidence-based care for this vulnerable patient group.

- Establish collaborative resource and data-sharing networks involving RACFs, GPs, Medicare Locals, and private businesses to ensure optimal efficiency in resource allocation and to remediate, where possible, current system gaps such as mobile imaging services, including plain X-rays, ultrasonography and echocardiography.

CARE-PACT provides a dedicated, hospital-based, single point of telephone contact for referral of deteriorating RACF residents for GPs, paramedics, RACF staff and community health providers. On ringing CARE-PACT, an acute gerontic nursing assessment (with emergency physician input and using a collaborative care planning approach) links the resident to one of four types of services, whichever is most appropriate for his or her care needs. These four types of services are described below with case examples. For each of these services, there is active involvement of the resident (or their substitute decision maker) in the collaborative care planning process.

ED/inpatient resource and early discharge service

The CARE-PACT ED/inpatient resource and early discharge staff assess and manage acute conditions common to RACF residents who cannot be treated within the RACF (see Case 1). This dedicated service:

- optimises continuity of care and effectiveness of discharge with informed collaborative care planning involving RACF staff and GPs

- improves quality of gerontic nursing care in the ED

- reduces hospital length of stay by having ED receive prior warning of a forthcoming ambulance transfer and facilitating early discharge through recognising and remediating barriers to discharge early in the presentation, and facilitating hospital acute-care substitution services for eligible residents.

Case 1

A woman, 72 years of age, is referred to CARE-PACT after an unwitnessed fall that resulted in acute pain to her right hip, on a background of 2 days of increased urinary incontinence and confusion. CARE-PACT advised transfer to the ED and contacted the ED physician at the referral hospital, who ensured that the ambulance was able to offload the resident in a timely manner. On arrival to the ED, the CARE-PACT clinical nurse informed the ED medical team of the collateral from the facility staff and GP, including a history of dementia, Parkinson’s disease and recurrent falls. Furthermore, the clinical nurse and the ED nursing staff (to foster education of ED staff) undertook:

- a cognition-appropriate pain assessment, identifying a need for further analgesia, prompting the ED staff to perform a femoral nerve block

- a delirium screen, which was positive, prompting an organic screen for infection, which revealed a urinary tract infection (in conjunction with the history of increased incontinence)

- a skin integrity check identifying a grade 1 pressure injury to the right buttock.

The clinical nurse then contacted the facility to relay the findings and to confirm that the facility has access to:

- a pressure reducing mattress

- physiotherapy services.

The resident had her neck of femur operatively managed on day 2 (24 hours after the last documented temperature) and had an uncomplicated post-operative course. She was discharged on day 4, with the discharge plan developed in collaboration with RACF staff and GP.

Mobile emergency assessment, care and treatment service

This service involves ED-trained CARE-PACT staff travelling to the RACF and reviewing patients with acute illness in their own environment after a telephone assessment by the CARE-PACT emergency physician confirms that this is a clinically appropriate option (see Case 2). Where indicated, the assessment involves the formulation, in consultation with the resident (or their substitute decision maker), GP and RACF staff, of advanced care plans and use of the Residential Aged Care End-of-Life Care Pathway (RAC-EoLCP).23 The presence of hospital-based staff within the RACF facilitates skills sharing, such that hospital and RACF staff develop enhanced capacity to provide appropriate patient care. Common conditions managed by the mobile assessment service include:

- fever unresponsive to oral antibiotics or requiring intravenous antibiotics

- lacerations or skin tears requiring sutures

- dehydration

- congestive cardiac failure

- uncontrolled symptoms in residents on a palliative pathway

- complications of indwelling catheters (IDCs).

Each patient interaction involving the mobile services of CARE-PACT is seen as an opportunity for educating ED staff, RACF staff, GPs and other health professionals about clinical care pathways and gerontic nursing care for defined conditions, in the context of a skills sharing approach, allowing each craft group to contribute their specific expertise to the consultation. Clinical pathways developed with broad consultation and endorsement, unlike pathways of existing services across Australia, are designed to be used by all professionals (RACFs, GPs, ED staff) across the care continuum and include key resources and referral guidelines. These pathways promote standardised, evidence-based, high-quality care of residents from the point of acute illness onset to, if needed, presentation to ED. They also provide a resource to assist RACF staff in identifying early deterioration of their residents, based not only on ‘traditional’ vital signs, but also on changes in functional and mental status that may be more readily detected by RACF staff. There is emphasis on early involvement of the GP as a key step in potentially preventing deterioration that may then necessitate transfer to ED.

Case 2

|

| Figure 2. Wound on resident’s left temple |

A man aged 92 years was referred to CARE-PACT for consideration of intravenous antibiotics for a chronic wound on the left side of his face, which had grown methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Figure 2). The wound had been first noted after a fall and, despite recurrent courses of antibiotics, there was no resolution of the discharge, nor healing of the wound. The resident was systemically well, had normal vital signs and no fevers. The CARE-PACT emergency physician reviewed a clinical photograph of the wound and, given the apparent raised edge (confirmed on subsequent review) and no evidence of surrounding cellulitis, determined that a more appropriate approach was a punch biopsy to rule out other diagnoses. Punch biopsy, performed in the facility, subsequently confirmed a squamous cell carcinoma and the resident elected to undergo an operative procedure.

Referral service to existing community or hospital-based teams

CARE-PACT partners with existing community and hospital-based services to facilitate linking of residents with acute care needs to the service best able to fulfill these needs (Cases 3, 4).Referral to existing services may be via telephone triage or following mobile emergency assessment team review. Existing services referred to include:

- hospital-based services (eg high-risk foot service, dermatology and endocrine tele-health services, day procedure unit)

- hospital-run mobile services (eg dementia outreach service, palliative care service, hospital in the home, alternate site infusion service)

- non-government organisation services (eg Alzheimer’s Australia, Ostomy Association)

- industry organisations (eg percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy trouble-shooting)

- private specialists and allied health providers

Case 3

A woman aged 78 years was referred to CARE-PACT for consideration of intravenous antibiotics for bilateral lower limb cellulitis unresponsive to repeated courses of oral antibiotics. The resident was systemically well, had normal vital signs and no fevers. A clinical photograph revealed bilateral lower limb erythema with occasional vesicles (Figure 3). Given the rarity of bilateral lower limb cellulitis and the chronic nature of the clinical findings, the CARE-PACT emergency physician facilitated a tele-dermatology review. A diagnosis of stasis (venous) dermatitis was confirmed.

|

|

Figure 3. Lower limb erythema

A. Bilateral lower limb erythema

B. Lower limb erythema with occasional vesicles |

The resident had the following management instituted to good effect:

- betamethasone diproprionate 0.05% ointment twice daily for 2 weeks then once daily for 2 weeks

- dermeze twice daily 2 hours after the betamethasone

(to continue even when skin not inflamed)

- soap-free wash only

- legs to be kept elevated when lying down

- grade I compression stockings (after confirmation of a normal ankle-brachial arterial index).

Case 4

A man aged 89 years was referred by his GP for consideration of intravenous antibiotics for management of pneumonia. He was febrile, with a temperature of 38.3°C, and his heart rate was 98 beats per minute, blood pressure was normal for him and oxygen saturation was 94%. In the 3 days prior to developing fever, he had been declining oral intake. His findings met Loeb’s clinical criteria for warranting intravenous antibiotics.21 Despite the resident having advanced dementia and significant comorbidities, there was no advance care plan. He was reviewed in the facility by the CARE-PACT emergency physician, after consultation with his substitute decision maker (SDM), who expressed a preference that he not be transferred to hospital. After clinical review, which confirmed clinical findings consistent with pneumonia and dehydration, and bedside blood tests revealing acute renal impairment, a meeting was held with his SDM outlining his clinical findings, likely prognosis and options for care. His SDM opted for a palliative approach in the RACF in view of his relative’s poor quality of life and wish not to have life prolonged by use of intravenous antibiotics. He was referred to the palliative care team who, in partnership with the RACF and GP, managed his symptoms in the facility and he passed away peacefully 4 days later. This case highlights the importance of advance care planning in decisions around management of this patient cohort.

Consultation service with GP leading to resolution of care need

CARE-PACT provides a consultative service for GPs regarding their resident’s acute healthcare issues. This process may result in resolution of the care need without a requirement for referral to another resource (Case 5).

Case 5

A woman aged 72 years was referred to CARE-PACT by her GP for intravenous antibiotics for management of a multi-resistant Escherichia coli. The urine was cultured on the basis of nursing reports of cloudy urine. The resident had no apparent urinary symptoms, no fever, no evidence of delirium (negative Confusion Assessment Method), and normal vital signs and clinical examination. The absence of localising symptoms and clinical evidence of infection suggested a likely diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria. On discussion with the GP it was agreed that the GP and RACF staff would defer antibiotic therapy, monitor vital signs and clinical condition regularly for 1 week, and refer to CARE-PACT if there were any concerns. The resident continued to be well in the absence of further antibiotic treatment, both at 7 days and 28 days follow-up.

Conclusion

Residents of RACFs are a vulnerable group whose acute healthcare needs, where these exceed the capacity of the GP and RACF staff to manage independently of the hospital sector, require a collaborative approach of health professionals across the care continuum. The aim of this approach is to maximise resident-centred care that avoids hospital transfers, where appropriate. CARE-PACT is a model of care that facilitates such care within a robust quality and safety framework. Early experience suggests the model is implementable and can be adopted in other jurisdictions, although its cost-effectiveness in specific sites will depend on geographic spread of RACFs, facility bed numbers and rates of ED presentation. In rural areas, for instance, where the number of facility beds and rates of ED presentation are lower than in metropolitan areas, it may be cost-effective to implement only some aspects of the CARE-PACT model, such as the care pathways and telephone triage. To date, no instances of preventable patient harm or inappropriate non-use of inpatient care have been reported. Health professionals across the care continuum appreciate the input that CARE-PACT provides in caring for their patients, and patients and families have welcomed the delivery of non-intrusive care within the facility. Over the next 12 months, more detailed process and outcome data pertaining to CARE-PACT will become available in an attempt to validate its operations and effects on patient care.

Competing interests: Ellen Burkett received a grant from the Health Innovation Fund for the CARE-PACT project.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding contributed by Health Innovation Fund (Queensland Health) and Greater Metro South Brisbane Medicare Local.

The authors also acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dawn Bandiera (CARE-PACT project co-lead) and Dr Raelene Donovan (CARE-PACT emergency physician), and the inspiration for the program provided by Dr David Green (Director of GCUH Emergency Department and founder of GCH Hospital in the Nursing Home).