Many guidelines recommend face-to-face psychological interventions, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), as a first step for the treatment of depression and anxiety.3,4 Although theoretically sound, in reality this can be difficult because of cost, availability and geographical limitations, despite recent changes in the availability of Medicare rebates for allied mental health professionals. Recently, internet therapies have been shown to be a validated and efficacious alternative to face-to-face therapies. Additional benefits include cost neutrality, unlimited scale and overcoming barriers of location and time.5,6 These therapies can be conceptualised as part of stepped care, being a simple and lower cost first step after which standard psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy protocols can follow. However, the current challenge is to increase the familiarity of internet therapies among GPs and to facilitate the widespread use of these therapies into routine care.7,8 The potential barriers to existing face-to-face care experienced by patients are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient barriers to face-to-face care

- Distance to care

- Time constraints

- Unavailability of suitably skilled professionals

- Privacy concerns

- Cost

- Stigma

- Unwillingness to disclose

- Childcare logistics

- Transport

- Physical disability and impaired mobility

|

What is e-mental health?

e-Mental health (eMH) refers to mental health services and information delivered or enhanced through the internet and related technologies.9 Broadly, it includes internet programs, telehealth, mobile phone applications and websites. This article focuses specifically on eMH resources and services that are delivered via the internet. These mental health services are available in two forms:

- automated self-help services such as online CBT

- clinician-supported online services.

Both forms are clinically effective, cost effective and acceptable.10–12 GPs can improve outcomes for patients who use these resources by being actively involved in their use, either as referrers, guides and mentors, or therapists. However, GP involvement requires that GPs know what is available and what their patients are using or would be open to using. In this article, we will consider:

- portals to care that are available to guide both patients and practitioners

- websites for psycho-education and support

- online therapy programs

- risks of eMH

- introducing eMH to patients

- online eMH training for GPs.

What evidence-based eMH resources are available?

1. Portals to care

Mind Health Connect (www.mindhealthconnect.org.au)13 is a website developed and funded by the Australian Government to provide information about mental health problems and access to all the Australian mental health services available online. A guided search helps users to find the resources they need.

Beacon (www.beacon.anu.edu.au)14 is a website developed by the Australian National University that rates online resources for a range of health issues in terms of their supporting evidence. It has a large section devoted to mental health resources and uses a simple classification system to rate the scientific evidence available for each resource.

2. Websites for psycho-education and support

There is a variety of reliable websites for GPs to recommend, depending on the mental health issues and the individual involved. A number of websites are especially designed for young people. The Black Dog Institute’s Bite Back website (www.biteback.org.au)15 is designed for those aged 12–18 years and is based on the principles of positive psychology. Its aim is to build skills in resilience and improve overall wellbeing in young people through interactive self-help activities, quizzes, blogs, forums, stories and videos, as well as educational information about various mental health topics. ReachOut (http://au.reachout.com),16 Headspace (www.eheadspace.org.au)17 and beyondblue (www.youthbeyondblue.com)18 all provide youth-focused websites. These websites present online CBT and positive psychology strategies designed to reduce distress and build resilience in a youth-friendly format. Other online services that provide reliable patient education and support for adults include Blue Board (www.blueboard.anu.edu.au)19 and Blue Pages (www.bluepages.anu.edu.au).20 Patients can find each of these sites independently but may not be aware that such sites are available, or that they can be effective tools for self-management of mental health issues. However, if their practitioner recommends these online programs, it is likely that patients would be more willing to use these resources. Asking questions about the online resources at follow-up, GPs may also increase the likelihood that patients will benefit from their use.

3. Online therapy programs

Each program has its own evidence base, but a summary of the evidence for eMH programs overall is outlined in Table 2. A small group of Australian institutions are responsible for developing most of the local online therapy programs.

Table 2. Evidence supporting the use of

e-mental health programs

- Depression – trials show effect sizes of eMH are at least as large as effect sizes for face-to-face psychological treatments in primary care and for antidepressant medications

- Anxiety – trials show that effect sizes for eMH programs are equivalent to face-to-face therapy for panic disorder and social phobia

- Effect sizes for anxiety are greater than for depression but this may reflect differences in the way participants were selected

- Conflicting evidence exists around the question of whether therapist guidance adds to the effect size

- Effectiveness has been demonstrated over the long term

|

The Australian National University’s MoodGYM program21 is free, well established and of proven value for moderate stress, anxiety and depression.

The Black Dog Institute’s myCompass22 is a free program for use on smartphones as well as computers. It provides CBT for mild-to-moderate stress, anxiety and depression in a modular format, with the additional benefits of real-time monitoring of mood and behaviour, reports, reminders, motivational messages and a diary.

This Way Up clinic at St Vincent’s Hospital and the University of NSW (CRUfAD) have developed a suite of CBT interventions called This Way Up23 for anxiety and combined anxiety and depression. Three of these programs (‘Shyness’, ‘Stress Management’ and ‘Worry and Sadness’) are available in a 3-module format free of charge. The 6-module evidence-based programs cost $55 for 90 days access and involve a referral and follow-up with a treating GP.

Macquarie University’s MindSpot clinic24 offers modular CBT for obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder and a wellbeing program designed for people suffering from mild-to-moderate stress, anxiety and depression. There is also an additional program specifically designed for the people aged ≥60 years. MindSpot provides email and telephone therapist support for participants while they are enrolled in the programs.

Self-guided assessment and CBT courses for the spectrum of anxiety disorders (eg panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and social anxiety disorder) are provided by Swinburne University at Anxiety Online.25 Self-help courses are free of charge and do not require a referral. Users who would prefer a therapist to guide them through the program can pay a fee of $120.00 for online therapist support.

Queensland University of Technology has developed the OnTrack suite of programs,26 which includes programs for depression, alcohol problems and comorbid depression and alcohol problems.

The University of Melbourne and Deakin University have developed resources for bipolar disorder, aimed at both consumers27 and caregivers.28

4. Risks of eMH

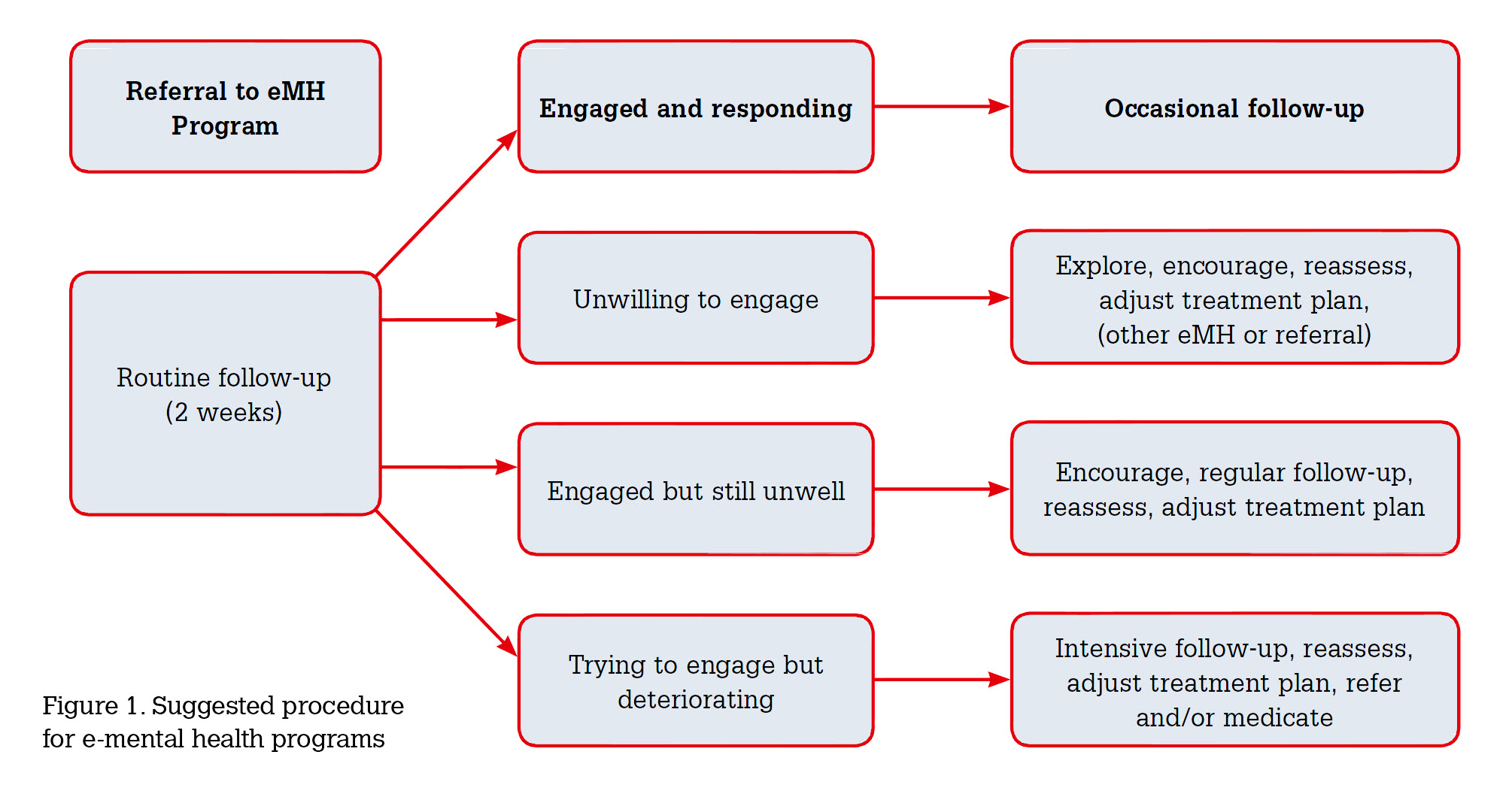

There are theoretical concerns about possible safety issues and risks in using eMH programs. Practitioners need to be aware that many programs can be found and accessed on the internet without the suggestion or direction of practitioners at all. There is no guarantee that the programs patients are using are likely to provide positive outcomes. Given that it is normative for patients to seek information on the internet, and sites vary widely in quality, it is appropriate for practitioners to take the lead in recommending and prescribing evidence-based programs to ensure that patients are using programs for which there is evidence of efficacy. Most programs contain mechanisms to alert the user or the referring practitioner (if one exists) to declining mental health and prompt the need for further action. However, it is important that practitioners arrange follow-up to review the content and impact of the program, as they would if they were prescribing medications or referring to a psychologist. A model for follow-up is outlined in Figure 1.

5. Introducing eMH to patients

GPs are aware that a significant proportion of the prescriptions they write are never filled. They also know that some of the medications that are dispensed are never taken or treatment courses not completed. It stands to reason that simply handing a patient a piece of paper with a website address will not lead to high uptake of eMH programs or good outcomes of their use.

Every GP has a unique style in engaging with patients and as they become more familiar with the idea of referring patients to e-mental health programs as a resource, will develop preferred methods to promote and guide patients through such programs. The referral process may be facilitated by incorporating eMH programs as one of the options available to a patient when developing a mental health treatment plan or when informally discussing the situation with patients.

In providing eMH as an option, it is helpful to briefly explain and demonstrate what that means for a patient. First and foremost, the GP needs to determine whether the patient has internet access. Although the majority of Australians now have access to broadband internet,29 there may be older patients or those with lower literacy levels who do not engage with internet technology. As such, GPs could consider arranging private computer access in their practices. Second, it is advantageous if the GP has a preferred eMH program in mind as this allows the GP to log on to that program within the consultation and familiarise the patient with the design and structure of the program. Some patients may prefer to investigate other options that are available for them, and may wish to look at the portal websites to choose a program for themselves. Guiding patients to these websites will ensure that they choose from quality, evidence-based programs. Third, discussing patient confidentiality within the internet program is also important. Some patients may have concerns regarding their personal information and it is important that their confidentiality is discussed prior to engaging with such programs. While safe and secure, internet programs operate using different security packages and consumers should be encouraged to consult the terms and conditions of their use.

Written material for use on GP desktops available at www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/eMHPrac30 explores the details of the eMH resources that are available. This information can be printed out and provided to patients for their consideration, accompanied by an explanation of how such a program could fit into the broader treatment plan. Table 3 provides a summary of the place that eMH programs can have in treatment planning in general practice.

GPs need to be mindful of not giving the impression that they are offloading their patients to cyberspace, even if the internet program is self-directed or does not have clinician support. To avoid this, it is necessary for the GP to clearly articulate the place that eMH programs will have in the overall treatment plan and make firm, time-limited arrangements for follow-up. This provides time frames for the patient and the opportunity to check wellbeing and compliance, encourage participation, overcome obstacles and assess whether alternative plans are necessary. It also ensures that the patient feels adequately supported by the healthcare system. Again, Figure 1 provides a guideline for such a follow-up procedure.

Table 3. Online therapy program descriptions and indicators

|

Online therapy program

|

Developing institution

|

Indications

|

|

myCompass

www.mycompass.org.au

|

Black Dog Institute

|

Mild-to-moderate distress, anxiety and depression

|

|

MoodGYM

www.moodgym.anu.edu.au

|

Australian National University, Centre for Mental Health Research

|

Mild-to-moderate distress, anxiety and depression

|

|

This Way Up

www.thiswayup.org.au

|

Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression (CRUfAD)

|

Panic disorder

Generalised anxiety disorder

Depression

Social anxiety

Mixed anxiety and depression

Obsessive compulsive disorder

|

|

MindSpot

www.mindspot.org.au

|

Macquarie University

|

Obsessive compulsive disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Mild-to-moderate stress, anxiety and depression

As above in over 60s

|

|

Anxiety Online

www.anxietyonline.org.au

|

Swinburne University

|

Specific programs for a variety of anxiety disorders

|

|

OnTrack

www.ontrack.org.au

|

Queensland University of Technology

|

Specific programs for depression, alcohol and for depression combined with alcohol use

|

|

MoodSwings

www.moodswings.net.au

|

Melbourne University, Deakin University

|

Bipolar disorder programs aimed at both consumers and carers

|

6. eMH training programs for GPs

e-Mental Health in Practice (eMHPrac) is a project funded by the Australian Government to provide training for GPs, allied health professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health professionals in the use of eMH resources and services.

Online training modules, webinars and fact sheets, developed at the Black Dog Institute by GP educators and online learning experts, introduce GPs to e-therapies and demonstrate how these tools and technologies can be integrated into primary care. By completing eMHPrac training, GPs and GP registrars can gain continuing professional development points with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, exposure to practical case studies eMH use in primary care, and learn strategies for achieving better outcomes for patients with mild-to-moderate mental health problems. Details of the training are available at www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/eMHPrac.30

Conclusion

In Australia, GPs have access to a variety of free online mental health resources that deliver standardised, high-quality treatment. These online resources may be accessed as stand-alone therapy, be incorporated into a stepped-care approach, or complement traditional mental healthcare. They are also useful in introducing patients to the experience of psychological interventions before referral for face-to-face therapy, to reinforce information provided within sessions, to provide the structure needed for patients to complete therapeutic activities between sessions, and to allow the patient to see their progress and review what they have learned. The programs can also provide maintenance treatment once patients have completed face-to-face sessions.

Given that <50% of patients in need of treatment actually receive it,31 these free online resources have the potential to fill a significant unmet need in Australian healthcare. Internet therapy overcomes many barriers to receiving treatment, such as cost, geographic location, timeliness and concerns about confidentiality and anonymity. Indeed, patients report high levels of satisfaction with eMH programs, and scientific evidence shows that these programs can be just as effective as face-to-face therapy. eMH resources can be used alone as self-help tools or are often a very useful adjunct to pharmacotherapy or face-to-face therapy. eMH can contribute to and optimise the care of the mental health symptoms while the practitioner takes care of the person as a whole. As such, we should strongly encourage GPs to be open-minded about their inclusion into standard mental healthcare.

Case

David, 32 years of age, is a GP registrar in the third month of his rural placement. His wife and 4-year-old daughter live in Sydney, 350 km away, where his wife works as a lawyer in a large firm. At weekends when he is not on-call, David drives to Sydney to see his family. He is finding the responsibility of a rural practice and isolation from his family more difficult than he anticipated. Additionally, the practice in which he is placed, although professionally supportive, is not open to providing personal support.

In the past few weeks, David has noticed marked fatigue and irritability. He has lost interest in his patients and has had difficulty concentrating during consultations. On one occasion he came close to shouting at a patient whom he felt was trying his patience with minor complaints. David experienced an episode of untreated clinical depression while under stress at university. David is aware that he requires assistance to deal with these issues, but is unwilling to talk to any of the local mental health professionals to whom he refers patients, because he is concerned about issues of anonymity and boundaries.

At a professional meeting, David hears about the Beacon website.14 He explores the website himself and discovers a number of sites and programs he can use for information and support. He is drawn particularly to the myCompass program,22 because it is free and allows registration with a pseudonym and without a referral. He also likes the idea of being able to use the program on his smartphone.

David has never had any training in CBT, but through using the techniques described in the program, he finds the myCompass program helpful and his mood somewhat improved. He also uncovers a wealth of material that he realises might be useful for use in his own practice with his patients. He reinforces what he has learnt on myCompass by exploring the OnTrack depression program26 and MoodGYM.21

Once he has completed the myCompass program, David decides he is now feeling and functioning well enough to continue with his rural placement. He is able to use the mental health ‘survival skills’ he has learnt to help him throughout his placement. He also finds that his newfound enthusiasm for online mental healthcare means he is more likely to suggest these programs to his patients, that his patients are more likely to use the tools and he is better equipped to guide them through the programs as part of their overall treatment plan.

Competing interests:

Various payments and reimbursements were made by the BlackDog Institute to Helen Christensen and Jan Orman. Their institutions also received government funding in relation to the e-Mental Health in Practice Project.

Fiona Shand received a consultancy fee from Lundbeck for advice on vendor selection for e-health intervention and an honorarium from Servier Laboratories for speaking at a conference.

Michael Berk has received various payments from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Servier, Pfizer, Sanofi Synthelabo, Solvay and Wyeth.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.