Case 1

A man aged 44 years, who tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), presented with a hard, painless anorectal lump that he noticed during self-examination. He had intermittent bright rectal bleeding for several weeks. He has had two male partners since he was last tested, two months earlier, for sexually transmissible infections (STIs) . He had condomless, receptive anal sex with both partners.

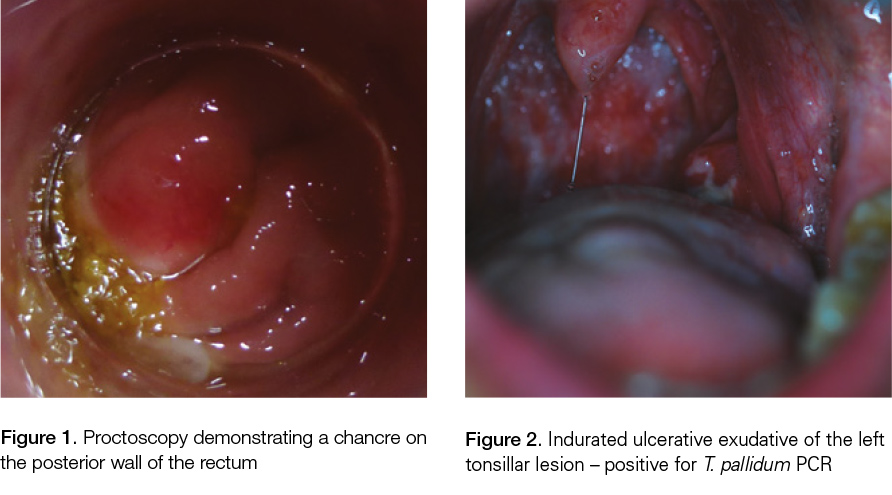

Proctoscopy confirmed a firm lump measuring 1 cm in diameter with superficial ulceration on the posterior wall of the anorectal junction 4 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy, genital ulceration or rash. An STI screen was performed, including a direct swab of the lesion via the proctoscope for the Herpes simplex virus (HSV), syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). The patient was contacted to attend for treatment five days later when his Treponema pallidum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result from the anorectal lesion returned positive. His syphilis serology was also positive: chemilluminescent immunoassay (CLIA), T. pallidum particulate agglutination assay (TPPA), immunoglobulin M (IgM) enzyme immunoassay (EIA) were all reactive, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was reactive with a titre of 256.

Case 2

A man aged 37 years, who had tested negative for HIV, presented with a small, painless, healing lump in the right pubic area and a sore throat he has had for several days. He also reported swelling in the left side of his neck, which he noticed on the morning of this presentation. He has had three male sexual partners since his last STI screen three months earlier. He had condomless insertive anal sex, protected receptive anal sex, and receptive and insertive oral sex with these partners. Physical examination revealed an ingrown hair in the right pubic area and a diffuse, non-tender swelling on the left side of his neck. He was screened for STIs and advised to follow up with his general practitioner (GP) if the neck swelling persisted.

The patient was contacted four days later with positive syphilis serology: CLIA total Ab, TPPA and IgM-(EIA) all reactive, and an RPR titre of 32. At the second visit, he reported night sweats and lethargy. On examination, there was a unilateral, indurated, ulcerated exudative swelling on the left tonsillar bed and associated left cervical tender lymphadenopathy (Figure 2). A fine erythematous maculopapular torso rash and several erythematous macular lesions on the soles were also present. The patient had not noticed the rash. Swabs from the tonsillar lesion were tested for T. pallidum PCR, HSV PCR and Streptococcus pyogenes culture. The T. pallidum PCR was positive.

Question 1

When should you consider syphilis in your differential diagnoses?

Question 2

What is a chancre?

Question 3

What investigations should you do if you suspect the patient has a chancre?

Question 4

In the context of rising rates of syphilis, what should you do?

Answer 1

The rate of syphilis among men who have sex with men (MSM), especially those living with HIV, has risen in many high-income countries since the early 2000s.1 This may have been accentuated in settings where HIV PrEP has been associated with increased number of partners and/or reduced condom use between men.2 Consideration should also be given to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in remote areas, who have increased risk of syphilis infection.3

Individuals may present to a health professional when there are obvious symptoms of syphilis, such as genital ulcers in primary syphilis or a rash from secondary syphilis. However, chancres acquired through oral or anal sex may be hidden in the oral cavity or anorectum, as illustrated in this case report. Taking a thorough sexual history may indicate the need to examine the mouth or anus. Differential diagnoses of anal lump or ulcer should include anal carcinoma and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Answer 2

A chancre is a lesion that develops at the site of T. pallidum inoculation. While clinicians may consider primary syphilis as mainly genital lesions, primary lesions in MSM may be oral or anorectal,4 reflecting acquisition from oral or anal sex. As chancres occur at the site of inoculation, these may also present in other sites, such as the cervix, and non-genital sites (eg lips, fingers), and are often painless and may go unnoticed.

Answer 3

T. pallidum PCR is a sensitive and specific test for primary syphilis and is more sensitive than dark ground microscopy.5,6 Serological testing for syphilis should also be performed where lesions of possible syphilis are present, but may be negative in the primary stage. While the clinician noticed the lesions on both men, in practice, such lesions may be overlooked by the patient and clinician. This may explain why some patients with serological evidence of early syphilis do not recall recent cutaneous lesions that are suggestive of primary syphilis when asked about these. Furthermore, primary syphilis can present as multiple painful lesions that mimics herpes, rather than a single, painless ulcer.7

At least annual screening for syphilis in MSM who are sexually active is recommended, with up to three-monthly screening for higher risk MSM (ie any condomless anal sex, more than 10 partners in the last six months, participate in group sex, use recreational drugs during sex, sexually active men living with HIV). This should be part of a comprehensive STI screen that includes urine, pharyngeal and rectal swabs for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, and an HIV test.8 Syphilis antibody tests (eg TPPA/TPHA, EIA/CLIA) are likely to remain positive for life, and non-specific syphilis tests (eg RPR) rise with new infection and decrease after treatment.

Answer 4

Clinicians should remain vigilant for syphilis when patients who identify as MSM present with mucosal or cutaneous lesions.4,9,10 Regular screening of MSM for syphilis will help detect syphilis earlier and allow treatment to stem further transmission. Contact tracing and treatment of all male and female sexual partners are advised, according to the Australian STI management guidelines for use in primary care.11 It is recommended that MSM should receive an annual

STI/HIV test, and up to four times a year for those at higher risk (eg reporting condomless anal sex).11

Key points

- The incidence of syphilis is rising in Australia, especially among MSM.

- Syphilitic chancres occur at the site of inoculation, which may be oral, anorectal or at other sites, and may be painless and go unnoticed.

- Clinicians should carefully examine the anorectum and/or oral cavity in patients who identify as MSM presenting with symptoms to exclude syphilis.

Authors

Jason J Ong PhD, MMed(Hons), MBBS, FRACGP, FAChSHM, Post Doctoral Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic. jong@mshc.org.au

Janet M Towns BMed, MForensMed, MPH, FRACGP, FAChSHM, FFCFM(RCPA), PhD candidate, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic

Marcus Y Chen PhD, FRCP, FAChSHM, Medical Services Manager, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic; Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic

Christopher K Fairley PhD, MBBS, Director, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred, Carlton, Vic; Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Vic

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who provided written consent to publish their clinical histories.

JJO (number 1104781) is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship.