Advance care planning (ACP) is a process whereby a person’s values and preferences for medical decision-making are made known.1 ACP initiates psychosocial mechanisms that enable thought and dialogue to acknowledge, clarify, document and share values, care preferences and end-of-life goals.2,3 ACP is an important step towards assuring that a person’s preferences and values are known at the end of their life.4

Despite the suggested benefits and implementation of ACP in Australia, Europe and North America for more than 20 years,3 the number of people completing ACPs is low. In the UK, 8% of a target audience surveyed had completed an ACP document of any kind.5 In Australia, ACP completion is believed to be low, although the exact figure is unknown. This is despite professional and public endorsement, coupled with supporting legislation in every state and territory.6–8

Barriers to initiating and completing an ACP are numerous. Health professionals reported barriers such as:2,9

- competing workplace demands

- fear of undermining people’s positive coping strategies

- depriving people of hope by talking about death

- lacking skills to have difficult conversations with patients and family.

In an Australian study of healthcare professionals, administrators and consumer representatives, it was suggested that low uptake was due to inadequate awareness of ACP, societal reluctance to discuss end-of-life issues and lack of health professional involvement in ACP.10

Increasing health professional engagement with ACP could be an effective strategy to overcome some of the barriers mentioned earlier.10 General practice, where trusted relationships already exist, might be the optimal location for introducing and promoting ACP.6,11,12 Consumers expect that general practitioners (GPs) will initiate end-of-life discussions.13 However, sufficient time, interest or skill needed to complete these discussions with the GP might suggest that other health professionals need to be involved.6 Co-locating skilled ACP facilitators in general practice could be an effective method to increase participation.

Background to the current study

Barwon Health is one of Victoria’s largest and most comprehensive public health services. It provides acute and subacute care, residential aged care and community health services to approximately 350,000 people in the Barwon region.14 One in six people in the Barwon region is aged over 65 years (n = 41,000; 16.5%),15 with 421 GPs providing services in 86 clinics.

Barwon Health modelled its ACP program, commencing in 2005, on the ‘Respecting patient choices’ initiative that is now overseen by Advance Care Planning Australia.8,16 Healthcare professionals with Barwon Health who cared for patients with chronic or life-limiting illnesses received training to complete ACP with their patients in acute and subacute care, aged care and community settings. In addition, an ACP facilitator was available to assist consumers with the process in an outpatient setting, and to train and mentor staff.

In 2008, the program was publically promoted to community members and healthcare providers, including GPs. Consumers who were referred to the program were consulted within community-based offices, and home visits were provided to those with physical incapacitation. Facilitators were nurses or social workers with additional training specific to the role. The ACP facilitator supported consumers to identify their values, goals and preferences regarding possible future treatment and end-of-life care and, in doing so, complete their ACP.17 Consumers were then encouraged to discuss and sign their ACP documents with their GP.

In 2010, the program expanded to include an ACP facilitator who is co-located at two general practices for four hours per week per practice. GPs and practice nurses referred consumers to the facilitator; the elderly and those with chronic or life-limiting illnesses were considered particularly appropriate for referral. In 2012, all general practices in the Barwon region were invited via the then Barwon Medicare Local to co-locate an ACP facilitator; 18 practices were willing and able to do so. Four facilitators provided 76 hours of service per week between these practices. Early in 2013, funding for the ACP program decreased and this reduced the ACP facilitator time to 60 hours per week, which was shared between 15 general practices and three facilitators. Within the Western Victoria Primary Health Network (previously Barwon Medicare Local), ACP was promoted throughout their general practice network and GPs attending ACP training workshops.

Study aims

The current study investigated whether co-locating ACP facilitators in general practice:

- increased the number of referrals to the ACP program

- increased the proportion of plans completed

- decreased the number of consumers declining participation.

Methods

Data collection

The ACP program routinely collected service-related data, including the number and source of referrals and plans completed, the number of consumers declining ACP when referred, and consumer satisfaction with the program, using a locally designed questionnaire. The questionnaire and a reply-paid envelope were mailed or handed to consumers who completed the ACP program, at the end of their final ACP consultation. The primary question was ‘Overall, how satisfied have you been with the advance care planning process and assistance provided by the “Respecting patient choices” program staff?’ Responses were collected using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = ‘Not at all satisfied’ and 5 = ‘Very satisfied’.

Data analysis

To determine if the number of referrals to the ACP program increased from the pre-substantive co-location period (2008–11; ‘T1’) to the post-substantive co-location period (2012–15; ‘T2’), the number of referrals for each period was counted and the percentage of change was calculated. The number of referrals from general practices with a co-located facilitator was distinguished from all other referral sources.

Chi-square tests were used to compare general practices with co-located facilitators to all other referral sources to determine if, during T2:

- a higher proportion of referrals were made

- a higher proportion of consumers referred to the ACP program completed an ACP

- a lower proportion of consumers declined ACP participation.

Consumer satisfaction was determined as being ‘Satisfied’ or ‘Very satisfied’ with the ACP process.

Ethical considerations

Barwon Health’s Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (reference 15/164).

Results

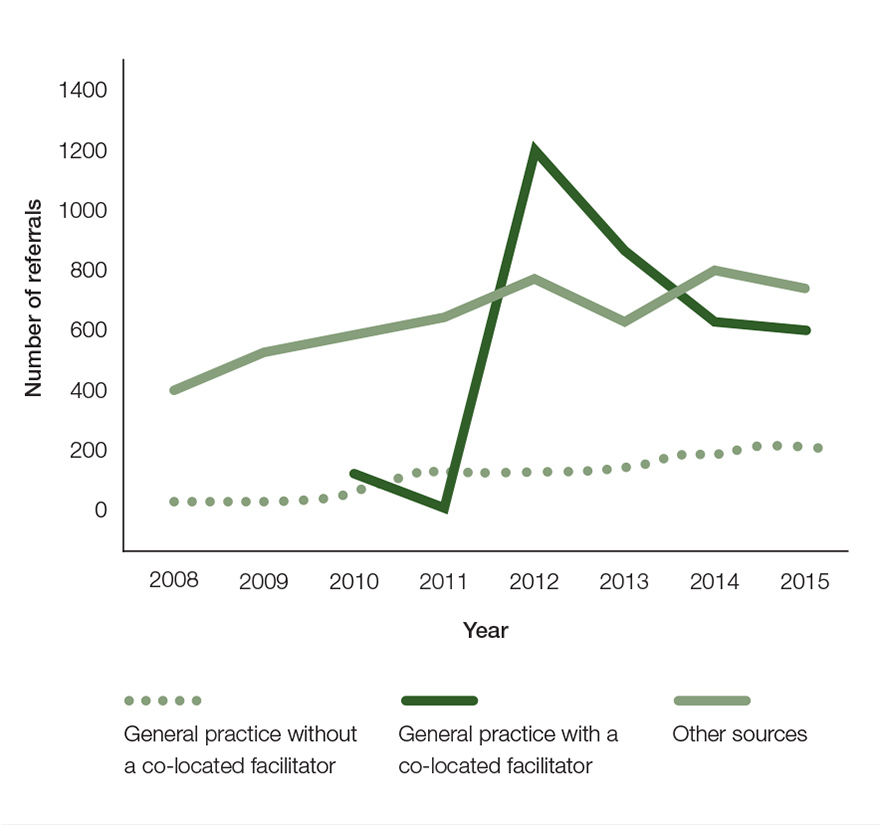

The ACP program received 2520 referrals between 2008 and 2011 (T1) inclusive and 6847 referrals between 2012 and 2015 (T2) inclusive. This represents a 172% increase in the number of referrals received from all sources (Table 1). During T2, general practice staff with co-located facilitators referred 47.6% of all referrals to the ACP program, significantly more than the prior period (ie T1; P <0.01). The largest number of referrals from co-located facilitators occurred in 2012, which subsequently decreased by 28.5% in 2013, 24.6% in 2014 and 9.4% in 2015 (Figure 1). The proportion of referrals that resulted in ACP completion varied significantly between referral sources during T2 (Table 1), with co-located facilitators resulting in plan completion 92.7% of the time (P <0.01). Two hundred and nine consumers (3.1%) declined ACP after they were referred to the program during T2 (Table 1). The proportion of declines varied significantly between referral sources during T2, with the highest proportion from all other sources (P <0.01).

The ACP consumer satisfaction survey was completed by 2776 consumers between 2008 and 2015, representing 33% of all consumers who were referred to the ACP program. Satisfaction scores were consistently high; at least 90% of consumers each year reported being ‘Satisfied’ or ‘Very satisfied’ with the ACP process and assistance provided by the program staff.

Table 1: Number of ACP referrals and completions, and consumers declining ACP

| |

2008–11

|

2012–15

|

|---|

|

Referrals*

|

n (%)

|

n (%)

|

|---|

|

From general practices with a co-located facilitator

|

112 (4%)

|

3256 (48%)

|

|

From general practices without a co-located facilitator

|

248 (10%)

|

688 (10%)

|

|

From all other sources

|

|

|

|

|

354 (14%)

|

683 (10%)

|

|

|

240 (10%)

|

118 (2%)

|

|

|

200 (8%)

|

388 (6%)

|

- Other community programs or services

|

588 (23%)

|

714 (10%)

|

|

|

778 (31%)

|

1000 (15%)

|

|

Total

|

2520

|

6847

|

|

Completions†

|

n (%)

|

n (%)

|

|---|

|

From general practices with a co-located facilitator

|

99 (88%)

|

3017 (93%)

|

|

From general practices without a co-located facilitator

|

127 (51%)

|

512 (74%)

|

|

From all other sources

|

|

|

|

|

148 (42%)

|

263 (39%)

|

|

|

86 (36%)

|

54 (46%)

|

|

|

137 (69%)

|

315 (81%)

|

- Other community programs or services

|

269 (46%)

|

351 (49%)

|

|

|

371 (48%)

|

606 (61%)

|

|

Total

|

1237 (49%)

|

5118 (75%)

|

|

Declines†

|

n (%)

|

n (%)

|

|---|

|

From general practices with a co-located facilitator

|

3 (3%)

|

59 (2%)

|

|

From general practices without a co-located facilitator

|

8 (3%)

|

3 (0.4%)

|

|

From all other sources

|

|

|

|

|

21 (6%)

|

55 (8%)

|

|

|

17 (7%)

|

6 (5%)

|

|

|

12 (6%)

|

6 (2%)

|

- Other community programs or services

|

29 (5%)

|

75 (11%)

|

|

|

4 (0.5%)

|

5 (0.5%)

|

|

Total

|

94 (4%)

|

209 (3%)

|

|

*Denominator = total referrals; †Denominator = number of referrals from corresponding source

ACP, advance care planning

|

Figure 1. Number of referrals per year to the advance care planning program by referral source

Discussion

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process whereby a person’s values and preferences for medical decision-making are made known.1 ACP initiates psychosocial mechanisms that enable thought and dialogue to acknowledge, clarify, document and share values, care preferences and end-of-life goals.2,3 ACP is an important step towards assuring that a person’s preferences and values are known at the end of their life.4

Everyone is entitled to die with dignity and respect as defined by their preferences and values.4 This study demonstrated that integrating ACP facilitators into general practice was an effective strategy for increasing participation and plan completion rates, while lowering decline rates.

From a healthcare provider’s perspective, co-located facilitators became part of the general practice team and promoted ACP during interactions with staff and at team meetings. Staff had increased awareness and knowledge of ACP, which might have increased their confidence and trust in the process, and their willingness to initiate conversations and refer to the program. A co-located facilitator also provided a convenient and simple referral pathway. Co-locating a facilitator had little impact on GP workload. From the consumers’ perspective, co-locating a facilitator in a trusted and familiar environment could be perceived as endorsing the importance and credibility of ACP.

Introducing ACP facilitators into general practices led to an immediate increase in referrals to the program. After 2012, the number of referrals from general practices with co-located facilitators decreased. This could potentially be due to:

- funding cuts reducing the number of general practices with a co-located facilitator

- reducing the number of hours provided

- fewer people at the practices with co-located facilitators who had not been previously referred to the ACP program.

Moving facilitators to other practices would create opportunities for more consumers to access ACP and lead to ongoing high referral rates; however, room availability in general practices was often a principal barrier to co-locating a facilitator.

Limitations of the study

The study was conducted in regional Victoria with a predominantly English-speaking community. Other ethnic and minority groups might access and interact with health services and ACP programs differently from our community,18 and our results might not be generalisable to regions with different demographic profiles. We did not investigate the cost-effectiveness of co-locating facilitators in general practice, or compare these costs to other ACP referral or completion methods. We compared co-locating facilitators in general practice to a range of other referral pathways; other methods of increasing ACP participation not included in the current study, such as providing access to an ACP facilitator at community health sites, could also be effective. We also acknowledge that our study investigated the development of an ACP: further studies would be required to analyse whether these ACPs are followed or needed at future time points.

Conclusion

The current study supports co-locating facilitators in general practice as an effective method for increasing ACP participation. We agree with recommendations to incorporate ACP into routine healthcare practices, preferably when the person is medically stable and has time to reflect on their values and preferences.19 Initiating and integrating ACP as part of routine assessments in general practice (eg health assessments for people aged 75 years and older introduced by the federal government), appears to be a sensible strategy for encouraging ACP conversations in general practice and subsequent referrals to ACP programs.

We estimate that less than 25% of consumers aged over 65 years in the Barwon region have participated in ACP despite more than 10 years of ACP endorsement and facilitation. Continued promotion and resourcing of ACP are required to ‘ensure people’s preferences are discussed, documented, actioned and reviewed by implementing advance care planning’.4

Authors

Jill Mann RN Div 1, PGCert (Crit Care), PGDip (Crit Care), Program Coordinator, Advance Care Planning, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic. jmann@barwonhealth.org.au

Stephen D Gill PhD, BPhysio, Health Services Research Coordinator, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Lisa Mitchell MBBS, FRACP, MPH, Deputy Director, Dept of General Medicine, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Margaret J Rogers BSc (Hons), PhD, Research Analyst, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Peter Martin MBBCh, BAO, MMed, FAChPM, Regional Director Palliative Care, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Frances Quirk BSc (Hons), PGCert (Ed), PGDip (Couns), PhD, Director of Research, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Charlie Corke MBBS, MRCP, FCICM, FJFICMI (Hon), Senior Intensive Care Specialist, Barwon Health, Geelong, Vic

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.