Most teenage pregnancies in Australia, as elsewhere, are unintended, and around half are terminated.1 Pregnant teenagers and their children are vulnerable to numerous adversities. However, if these young people receive appropriate healthcare intervention, including non-judgemental medical and psychosocial support, outcomes can be improved for both the young parent and their child. We recognise that teenage fathers also have important health and wellbeing concerns, but in this review we focus on teenagers who become pregnant, teenage mothers, and their children. Box 1 summarises clinical recommendations for general practice.

Box 1. Interventions and practice recommendations for the general practitioner

|

Establish trustful relationships with young patients

Ask about substance use, relationships, experience with violence and sexual abuse:

- Validated screening instruments recommended by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists include TACE and Substance Use Risk Profile Pregnancy Scale.

- For general mental health screening, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire can be scored instantly online (www.youthinmind.co.uk).

- Screen sexually active teenagers annually for sexually transmissible infections (STIs)

- Confirm hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccination status and test and vaccinate if coverage is incomplete

Identify teenagers at increased risk for unintended pregnancy:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, disadvantaged or rural/remote residents

- Born to teenage mothers

- Home life is disrupted or abusive

- Sexual abuse survivors

- Teenage mothers

Act to reduce the risk of unintended adolescent pregnancy:

- Sensitive and developmentally appropriate exploration of pregnancy and contraceptive beliefs

- Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) have been shown far more reliable in this age group than any other option, and should be the first-line recommendation

- The Family Planning Alliance of Australia provides training in intrauterine device and contraceptive implant insertion (http://familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au/services/)

- Developmentally appropriate sexual health and contraceptive counselling, with particular attention to correct condom use, access to condoms and emergency contraception

Where unintended adolescent pregnancy occurs:

- Provide nonjudgmental support and counselling, including all options

- Screen for sexual abuse and exploitation, particularly among younger adolescents – coercive relationships may be difficult to identify, as many adolescents who fall pregnant to older partners describe caring, consensual relationships

Antenatal care:

- Assess nutritional adequacy

- Screen for STI and bacterial vaginosis at first antenatal visit, third trimester, postpartum and where symptomatic; for positive STI tests, treat partners presumptively

- Screen routinely for alcohol use, substance use, violence and mood disorders each trimester

- Provide access to smoking cessation

- Teach about signs and symptoms of preterm labour

- Discuss contraceptive options before delivery

- Encourage and facilitate breastfeeding

- Include fathers where possible

Postpartum and beyond:

- Encourage return to school and continuing healthy lifestyle changes made during pregnancy

- Facilitate home visitation by nurse where possible for enhanced support

- Screen regularly for alcohol and substance use, violence and mood disorders

- Assess nutritional adequacy, particularly of breastfeeding mothers

- Provide access to smoking cessation

- Reinforce contraceptive options, particularly LARCs, and safer sex

|

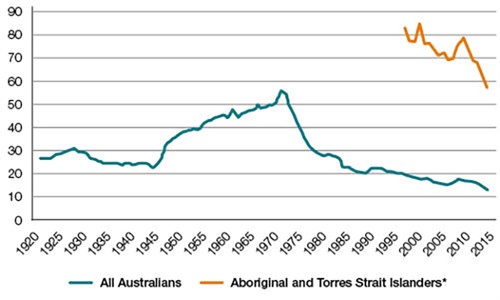

Teenage births over-represented in some communities

The teenage fertility rate is the number of births per year per 1000 females aged 15–19 years; rates in girls under the age of 15 years are unstable because of low numbers and are not routinely collected. The fertility rate among Australian teenagers fell to a historic low of 12.9 births/1000 in 2014 (Figure 1).2 This downward trend has been attributed to Australian teenagers’ increasing control of their fertility.3 The legalisation of abortion in some states and territories may also have contributed to this decline, but access to medical and surgical abortion is highly variable by region, rurality, and individual socioeconomic status. Barriers to pregnancy termination and contraceptive services are more pronounced for teenagers.

Figure 1. Births per 1000 females aged 15–19 years among all Australians and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, 1921–2014

*National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data have been published only

since 1997. Data source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia

Teenage fertility rates are not consistent across the Australian population. The birth rate for teenagers living in the most rural and remote areas is 57/1000 per year, and those living in the most socially disadvantaged areas have birth rates almost eight times higher than those in the most advantaged areas (30 versus 4 births/1000).4 Nationally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenagers have a fertility rate of 57/1000, which is more than four times higher than in the general population (Box 1).2 The disparity is even greater in Western Australia where, in 2014, there were 88 births per 1000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenagers, and 15 per 1000 teenagers in the general population.2

Earlier age at first sexual intercourse increases risk of teenage pregnancy

In Australia, the median age of first intercourse among teenage females has decreased to 17 years.5 Teenagers who start sexual activity at a younger than average age are at greater risk of unplanned pregnancy and early parenthood.6 Risk factors for earlier sexual activity are early puberty, childhood adversity, low socioeconomic status, dysfunctional family relationships, childhood sexual abuse, single-parent or blended family structure, poor school adjustment, adolescent depression, low self-esteem, and childhood externalising behaviour.7–9 Thorough history-taking should include assessment for these risk factors.

Inconsistent or ineffective contraceptive and condom use

Not using effective contraception at first sexual intercourse increases the risk of an unintended pregnancy and abortion.10 However, we do not have national data on the contraceptive behaviour of teenage parents. Nationally, 91% of male and 97% of female adolescents report using contraception at first intercourse.5 Despite this, Australian adolescents’ knowledge of the most effective contraceptive options is poor.11,1.Young people report a variety of barriers to access to prescribed contraception, including discomfort in disclosing and discussing concerns, concerns about confidentiality, and expense.13 Rural/remote settings have fewer providers and longer waiting times.

Brief one-on-one counselling sessions by general practitioners (GPs) have been shown to modify condom and contraceptive behaviour in adolescents,14 and multiple interventions (combining health education with contraception promotion) have been shown to reduce teenage pregnancy.15

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are the most effective, are well tolerated and have high continuation rates.16 Contrary to widely held misconceptions, intrauterine devices can be inserted safely in a primary care setting, and there is no increase in the risk of infection, perforation or bleeding in young or nulliparous women.17 Despite LARC methods being recommended as first-line for adolescents,17 uptake in this age group (7.5%12) appears to be limited by misinformation about their suitability and side effects, as well as their relatively high upfront costs and the requirement for a specially trained clinician.18

Family disruption and violence is a common experience for pregnant and parenting teenagers

Teenage motherhood is intergenerational: the daughters of adolescent mothers are more likely to become teenage mothers themselves.19,20 Disrupted family structure with parental separation, and social disadvantage, are common.21 Family violence has also been associated with subsequent teenage pregnancy.22

Physical and sexual maltreatment during childhood are associated with teenage pregnancy.23 One fifth of pregnant Australian adolescents experienced violence from a partner or family member before age 16 years.24 Teenage mothers may be at higher risk of family violence,25 possibly because of a link between partner violence and reproductive coercion.26 Screening for partner and family violence should be routine in the primary care setting, but as pregnant teenagers and teenage mothers are often exposed to stigma and isolation, this increases the difficulty of addressing it clinically. This presents challenges to the GP that can be addressed in part by having previously laid the groundwork of engagement with the teenage patient.27

Sexually transmissible infections are more common in pregnant teenagers

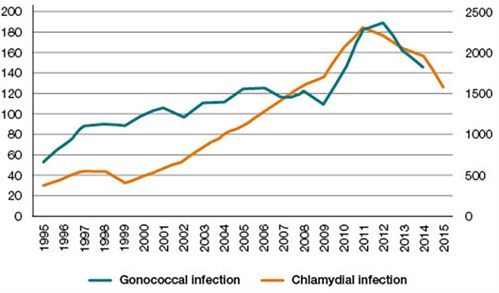

The incidence of sexually transmissible infections (STI) is particularly high among pregnant teenagers.28 STIs increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for mother and child. Rates of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among women aged 15–19 years rose through the 2000s, and have fallen slightly in recent years (Figure 2).29 Untreated chlamydial infection is associated with preterm labour, premature rupture of membranes and low birthweight; untreated gonococcal infection is additionally associated with pregnancy loss and chorioamnitis. Both infections transmitted during delivery can cause blindness. The risk of STIs is much higher in young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women than in their non-Indigenous counterparts: a fourfold increase in the the risk of chlamydia, and 70 fold increase in the risk of gonococcal infection.30

Figure 2. Chlamydial and gonococcal infection rates per 100,000 females aged 15–19 years

Data source: Australian National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System

Patients may not readily reveal behavioural risk factors in routine antenatal history-taking, so testing should be guided by risk groups. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and Australasian Sexual Health Alliance (ASHA) guidelines recommend routine annual chlamydia screening in all sexually active young people (15–29 years) and pregnant women.31 Gonorrhea screening is recommended only for high-risk populations, such as Aboriginal and Torres strait Islander people living remotely. General STI screening is recommended in all women at the first antenatal visit and in the third trimester, postpartum period and where symptomatic.32 Postpartum teenagers should be advised on the use of condoms with all new partners and prescribed LARC to prevent a repeat pregnancy.

Smoking is common in pregnant and parenting teens

Around 35% of adolescents smoke during pregnancy.4,33 Although smoking rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been decreasing, female Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescents continue to be three to four times more likely to smoke than their non-Indigenous counterparts.34 Smoking cessation rates in pregnancy have been rising, but teenagers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and remote residents are less likely to stop smoking during a pregnancy.35 Teenagers are also more likely to resume smoking in the peripartum period.36

Smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period carries extensive risks for mother and child. Smoking during pregnancy carries a stigma, so pregnant women may be less likely to ask for assistance to quit.37 Consequently, it is recommended that physicians ask pregnant and breastfeeding adolescents about smoking at every patient contact during and after pregnancy. ‘Vaping’ and waterpipe use, although less common and less a focus of guidelines, should also be assessed.

Evidence-based strategies for cessation include counselling, pregnancy specific self-help materials, referral to QuitLine, problem-solving and facilitating social support.38 Nicotine replacement is less risky than continuing to smoke, but there is no evidence for its efficacy in long-term smoking cessation among pregnant women or among adolescents. Varenicline and bupropion are not licensed for use in people under the age of 18 years and have not been shown to be safe or effective for smoking cessation treatment in pregnancy.38 Multifaceted interventions may be needed to address the complex relationships underlying motivation for smoking and use of other substances.39

Alcohol and other drugs are also used more commonly by pregnant teenagers

Recent Australian data on the use of alcohol and other drugs during pregnancy are sparse. Pregnant adolescents who use alcohol and other drugs experience societal scrutiny in relation to their capacity to protect their child, and risk losing custody.36 In the late 1990s, consumption of alcohol, marijuana, solvents and heroin was shown to be higher among pregnant Australian adolescents than in the general population of pregnant mothers.24 A small Australian study of young pregnant smokers found 43% used illicit drugs.40 The most recent National Drug Strategy Household Survey found that among all pregnant women surveyed, 42% had used alcohol, 2.2% had used illicit drugs and 0.9% had misused prescription drugs during pregnancy.41 US data show that adolescent mothers are more likely to use alcohol and other drugs, and less likely to complete treatment than adolescent females generally.42,43

Short-term perinatal complications

Pregnant adolescents present later to antenatal care, particularly if they are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders or rural/remote residents. Pregnant adolescents experience anaemia, urinary tract infection and pregnancy-induced hypertension more often than adults.44,45 Preterm birth, low birthweight, stillbirth and neonatal death are also more common outcomes for adolescent than adult pregnancies.33,45 Most of the disparities in neonatal death can be attributable to preterm birth, low birth weight, maternal biological immaturity, or lack of access to prenatal care. Group antenatal care has been shown to increase clinic attendance and breastfeeding, and reduce preterm birth among young women.46Nurse home visits in the antenatal and postnatal period have been shown to improve short-term and long-term health outcomes among adolescent mothers and their children.47

More positively, risks of caesarean and instrumental delivery are lower among adolescent than older mothers,48 although adolescents aged 15 years and younger are more likely to experience caesarean births for the indication of presumed cephalopelvic mismatch than older mothers.48 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers may be less likely to undergo a caesarean or instrumental delivery than non-Indigenous mothers.33,49

The rate of stillbirth among all Australian teenage mothers has risen from 9.5/1000 births in 1991 to 15.0/1000 in 2009.50 This may reflect a selective decrease in teenage pregnancy among more advantaged teenagers, who have fewer risk factors for stillbirth.51 Stillbirth rates are decreasing among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, but remain higher than in the general population.33,52

Longer term health and psychosocial adversities

Socioeconomic disadvantage is both an antecedent and consequence of teenage motherhood.53,54 Educational underachievement is particularly common among teenage mothers. Lower education contributes to reduced employment opportunities, and both perpetuate poverty.54 These disadvantages and the increased likelihood of adverse birth outcomes place children of teenage mothers at increased risk of poor health, educational disadvantage and social adversity.55 Socioeconomic disadvantages conferred persist well into adulthood.56 Evidence suggests that children of teenage mothers may have behavioural, emotional and cognitive disadvantages.55,57 GPs should encourage return to education after pregnancy.

Teenage mothers are at risk of further unintended pregnancies, including rapid repeat pregnancy (pregnancy within two years of the first).58 The use of LARC was shown to reduce rapid repeat adolescent pregnancy in an Australian sample and can be offered postpartum in hospital settings.59 The GP can play an important role in discussing this possibility at antenatal visits, and in requesting that hospitals arrange LARC before discharge. Depression is much more prevalent among pregnant teenagers than their adult counterparts or teenagers in general.32 Untreated depression may be related to increased maternal risk of premature death and suicide, and intergenerational disadvantage.60 Having a child as a teenager may have a long-lasting adverse effect on mental health that is only partly explained by socioeconomic status.61,62 GPs should routinely assess mental health in pregnant and parenting teenagers.

Policy recommendations

- Advocacy for evidence-based programs to support teenage mothers (eg local resources such as Victoria’s ‘Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies’ program; home nurse visiting programs) should be encouraged

- Additional support, such as bulk billing and reimbursement for ultrasonography without qualifying pregnancy complications, should be provided for access to care for this usually impoverished population.

- More research into the rates of and intervention strategies for partner violence, alcohol and other drug use, and strategies to promote increased uptake of LARC among Australian teenage mothers is required.

Authors

Jennifer L Marino MPH, PhD, Research Fellow, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic; Royal Women’s Hospital, Parkville, Vic

Lucy N Lewis MN, PhD, Midwifery Research Fellow, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedicine, Curtin University, Bentley, WA; Department of Nursing and Midwifery Education and Research, King Edward Memorial Hospital, Subiaco, WA

Deborah Bateson MA, MSc, LSHTM, MBBS, Medical Director, Family Planning New South Wales, Sydney; Clinical Associate Professor, Discipline of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Neonatology, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Martha Hickey MSc (Clin Psych), MBChB, FRANZCOG, MD, Head of Department, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic; Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Vic

S Rachel Skinner MBBS, PhD, FRACP, Professor, Discipline of Child and Adolescent Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW; Adolescent Physician, Children’s Hospital Westmead, Westmead, NSW. rachel.skinner@sydney.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

References