In Australia, children and young people under the age of 18 years who cannot live with their families because of neglect, abuse, abandonment or death of parents are placed in out-of-home care. This process is initiated by a report to the relevant state or territory child protection service and, once verified, is subject to legal processes administered by the courts. Out-of-home care refers to three main types of care:1 kinship, foster and residential care. Kinship care is provided by people known or related to the child. Foster care is pro-vided by volunteers in their own homes; the volunteers receive a government subsidy. Residential care refers to group homes of up to four young people, supported by paid, rostered staff.

In general, residential care is provided to young people aged >12 years and up to 18 years. However, in some instances, younger children may be placed in residential care settings to keep sibling groups together. Residential care is generally the preferred option for young people aged >12 years with complex needs, a history of placement instability, and who do not manage in a family environment.2 Unfortunately, residential care has also been described as a ‘place of last resort’ and criticised for exposing young people to high rates of drug-taking and other risky and criminal behaviours.3

The three forms of out-of-home care in Australia have replaced the institutional care of the recent past, as a solution to better care for vulnerable young people. Orphanages and other types of institutional care have been (and still are in many countries) associated with conditions that are detrimental to mental and physical health, including strict routines, lack of personal relationships, isolation from wider society and, regrettably, abuse.4 Foster care programs need to be well designed and support stable placements; unstable placements are likely to be as harmful as institutionalisation to a child’s future mental health and function.4

A range of court orders exists to address the short-term and long-term care requirements of young people. Their outcomes range from short-term loss of guardianship to permanent care or adoption by carers. These differing arrangements mean that guardianship may be held by biological parents, kinship or foster carers, or the state or territory. There is no lower limit to the age that children can be placed in out-of-home care. Currently, the upper limit is 18 years.

Young people in out-of-home care typically have worse mental and physical health outcomes than their peers who grow up within a family of origin.5–7 This may be due to adverse experiences prior to or during out-of-home care, inadequacies in addressing mental health and wellbeing in care, and the systematic undermining of any sense of stability that might have been achieved in out-of-home care that is associated with enforced withdrawal of services (‘leaving care’) at 18 years of age.8

The number of children in out-of-home care has grown by 20% between 2010 and 2014.1 Carers face increasing burdens in providing care while being important sources of support.9,10 In 2014–15, 54,025 children and young people were in out-of-home care in Australia. One in 20 were in residential care settings, with some variation between the states.11 Significant levels of sexual and physical abuse, and neglect of young people in care, particularly residential care, have been recently reported.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people are over-represented in out-of-home care (52.5 per 1000 children versus 8.1 per 1000 children among non-Indigenous Australians).11 Past federal, state and territory government policies (resulting in, for example, the Stolen Generation) have contributed to the loss of family structure and connections, language, culture and land (S Lindstedt, KMS, C Black, HH, unpublished data). Present policies directly affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families,3,13 and liaison with Aboriginal community controlled health services is indicated for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care and their carers.14

Therapeutic goals of care

General practitioners (GPs) are seen as crucial to establishing and maintaining continuity of healthcare for children in out-of-home care. One of the first tasks of the GP is to identify that the child lives in out-of-home care, to take as much history as possible about placements, and establish a relationship with the child and carer. The carer may have limited information about the child’s health and life, as some children experience multiple placements during the out-of-home care period. The carers may also feel left out or ignored, and less consulted and informed than they would like to be.

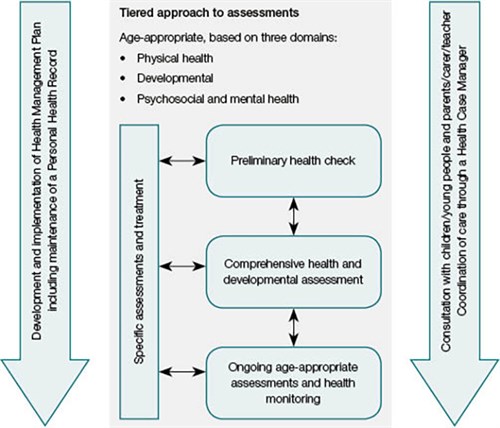

The National clinical assessment framework for children and young people in out-of-home care (National Framework)15 proposes a tiered approach to identifying and responding to these young people’s health needs (Figure 1). This National Framework recommends a collaborative approach between the GP, the young person and their ‘care team’ to achieve the best outcomes. As a minimum, this team should include an out-of-home care case manager and/or child protection case manager, biological parent or other family member, carer, as well as health professionals. The out-of-home care case manager will usually take responsibility for practicalities such as appointments. However, depending on the care order and who holds case management responsibilities, this might be the responsibility of the carer or child protection case manager.

Figure 1. National clinical assessment framework – Children and young peoplein out-of-home care

Reproduced from the National Clinical Assessment Framework for Children and Young People in Out of Home Care, Department of Health, Australia, 2011

Considering the likelihood of a complex mix of mental and physical health problems, along with marked social and relational problems (eg severe traumatic experiences and mistrust of others), clinicians are encouraged to initially focus on creating a safe and trusting environment. Techniques to achieve this include active listening, demonstrating warmth and genuineness, and encouraging and enabling the young person to participate in their own healthcare decisions. The Blue Knot Foundation’s Factsheet for general practitioners – Understanding complex trauma16 emphasises ‘trauma-informed practice’, which pays careful attention to the relational context of treatment. Treatment can be experienced as re-traumatising, even if unintended, if the young person does not feel that the practitioner has listened , or if the practitioner is perceived to be untrustworthy or intimidating. This is especially the case if treatment involves practices that the young person experiences as coercive, controlling or potentially punitive. Such experiences can result in the young person feeling misunderstood or punished, and/or mistrusting the healthcare practitioner. A professional, expert manner can facilitate trust when it is balanced with validation of the young person’s experience, regardless of whether this experience does or does not make sense to the practitioner at the time. While practitioners might see this as excessively time-consuming or indulgent, investing in this aspect of care ultimately facilitates information sharing and good outcomes.

This assumption of young people’s capacity to make informed choices about their healthcare may often be in marked contrast to the young person’s beliefs and actual experience that, as a consequence of being ‘in care’, they have very limited agency or control over their life.

Preliminary and comprehensive assessments for young people in out-of-home care

The National Framework recommends a preliminary health check within 30 days and a comprehensive health and developmental assessment to be conducted within the first three months of a young person entering out-of-home care placement. The National Framework aims to redress the fracturing of care by promoting integration and planning across the physical and mental health, developmental and psychosocial domains. Therefore, the resulting health information should be integrated with that derived from other assessments (eg educational or vocational) into a comprehensive management plan for the young person. As many young people present with complex problems, it is very likely that these health assessments will indicate the need for paediatric or psychiatric referral. Early involvement of such specialists is also important for the support of carers.

Common problems: Mental, psychosocial and developmental

Young people in residential care can experience a range of health and psychosocial problems (Table 1).17

Table 1. Research evidence for common health and psychosocial problems for young people in out-of-home care

|

Physical health problems

|

|---|

|

Poor nutrition, obesity and lack of exercise

|

62% of young people in residential care are overweight or obese (versus 27% of general population of young people)6

|

|

Dental

|

Half of Australian children entering out-of-home care have dental problems10

|

|

Tiredness and sleep

|

23% of young people in out-of-home care do not get enough sleep.34 Sleep problems are associated with mental ill-health in younger children in out-of-home care.35 Less is known about the mechanisms of sleep disturbance in adolescents in out-of-home care

|

|

Sexual and reproductive health, including contraception, early pregnancy and sexually transmissible infections

|

Young people with experience of out-of-home care reported engaging in sexual activity at an earlier age; having more sexual partners; a greater likelihood of engaging in sex in exchange for money, goods or services; and a higher prevalence of sexually transmissible infections.36 One third of young women had become pregnant or given birth within one year of leaving care37

|

|

Asthma

|

Young people in residential care have fewer outpatient visits for asthma but are four times more likely to be hospitalised for asthma than other young people.7 This is despite higher rates of prescription of controlled medications for young people in residential care. The stressful nature of residential care settings, and the frequency of behavioural and mental health issues among young people, may be triggers for asthma attacks. Lack of access to primary healthcare may contribute

|

|

Mental health and psychosocial problems (social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing)

|

|---|

|

Substance use and addictions

|

Out-of-home-care populations engage in earlier initiation to tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, and report higher and escalating rates of illicit drug use on exiting care38

|

|

High levels of psychological distress and behaviour problems

|

45% of young people in out-of-home care have a diagnosable mental disorder, versus 10% of their peers.5 Externalising and behaviour problems are three times more common34

|

|

Criminal behaviour and youth justice involvement

|

Young people under a child protection order are 23 times more likely to be under youth justice supervision in the same year, compared with their peers39

|

|

Suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide

|

Just under 50% of young people had attempted suicide within four years of leaving care37

|

|

Educational, health and social problems

|

Young people in residential care are more likely to have changed schools or received special or remedial education compared with young people in home-based care.34 Non-attendance at school is reported by 27% of young people in residential care

|

Developmental delay is common and may be due to genetic, environmental or interactional effects, and can affect responsiveness to other treatments.18 Common problems include intellectual impairment, such as learning, communication, language and speech difficulties; autism spectrum disorders; and sensory–motor disturbances. As a result of limited and disrupted access to healthcare and education, these problems are diagnosed much later than in the general population, and the opportunity for early intervention might be missed.

Mental health and psychosocial problems constitute the greatest disease burden among young people.19 Those in out-of-home care have higher rates of mental disorder than their non–out-of-home care peers and are less likely to access care in a timely manner.5,20–23 Proactive, regular and voluntary help-seeking is infrequent among vulnerable young people.22 Along with the common mental state disorders (eg mood, substance use, and post-traumatic stress and anxiety disorders), severe personality disorder, especially borderline personality disorder (BPD),24 is also relatively common among young people in out-of-home care. People with BPD have been unjustifiably stigmatised, but Australian treatment guidelines suggest there is cause for optimism in the treatment of BPD.25 Chanen and Thomson provide helpful prescribing advice on BPD.26

Recent research suggests that some young people preferred to be supported by carers who could communicate and attempt to understand their needs, over being ‘sent for counselling’ (unpublished data, K Monson, C Humphreys, C Harvey, S Malcolm, HH). There are factsheets to assist GPs to manage the broad range of challenges encountered by young people in out-of-home care.16 First-line treatment is most often psychosocial and includes counselling or psychotherapeutic approaches.16 Medication may be indicated for more severe mental disorders, but should be prescribed judiciously and monitored regularly for effectiveness and safety. Failure to respond to an adequate trial of medication would normally be an indication for psychiatric referral. Those with particularly complex or persistent problems may need multidisciplinary teams that are more likely to be available at a child and adolescent/youth mental health service. Such programs may include developmental delay/autism spectrum screening, mobile youth outreach, or early intervention for BPD.22,27,28 Wait times for such programs can vary widely, and while there are some with considerable wait lists, others have developed ways to prioritise those most in need.

The national headspace network of youth mental health centres provides accessible care for young people with mild-to-moderate mental health problems. GPs can refer young people with complex presentations to child and adolescent/youth mental health services.29 Young people in Victoria who are child protection clients and in out-of-home care do not need to meet the full criteria for a diagnosis of a mental disorder to access public mental health services.29 Nonetheless, young people in out-of-home care experience extraordinary difficulties in accessing necessary tertiary mental health services. The process can be time-consuming and frustrating for GPs and for the patients. In the most difficult situations, especially where there is perception of a very high level of risk for the young person, practitioners are advised to consult with the relevant director of the clinical mental health service or, ultimately, with their state or territory chief psychiatrist.

Ongoing assessment and monitoring

Ongoing assessment and monitoring are recommended in the Department of Health’s National clinical assessment framework. This might be challenging when working with young people who have multiple changes in placements, care staff and case managers. Detailed record keeping, good relationships with care team members, and ‘trauma-informed’ care with carers and the young person can assist GPs to provide effective and consistent ongoing healthcare. Suitable Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items can be found in the Department of Health’s National clinical assessment framework.15

Legal considerations

As with the treatment of any young person, GPs should first explain confidentiality (and its limits), along with mandatory reporting obligations. Given the high rates of physical and sexual abuse that occur while young people are in out-of-home care,12 GPs should be aware of the mandatory reporting requirements in their state or territory. A list of these requirements can be found at the Australian Institute of Family Studies website.30 Each state and territory is responsible for legislation governing child protection. Therefore, definitions of the need for care and protection, and the types of protection orders, differ across each jurisdiction. Consent for treatment of a person under 14 years of age must be sought from the guardian in the case of finalised guardianship, third-party parental orders and some administrative orders. In all other orders, the biological parents maintain legal guardianship and their consent is required for medical treatment. Patients under 18 years of age can consent to their own medical treatment, without their parents’ or guardian’s knowledge, if a doctor assesses that the young person has sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable them to fully understand the proposed treatment and also the consequences of not having the treatment. Young people fulfilling this requirement are referred to as ‘Gillick competent’ or a ‘mature minor’.31 Being in out-of-home care does not automatically exclude a young person from being a mature minor. Indeed, some young people have had extensive life experience and are well practised in such decision making.

Therapeutic challenges

The challenges associated with treating young people with complex health needs are best addressed by following basic principles.16 While these may seem to be ‘common sense’, it is important to acknowledge that the many and varied challenges posed by these young people can push even the most professional clinicians to provide less than adequate care. For example, a young person with disruptive and aggressive behaviour is not likely to be the one a clinician feels inclined to follow up after a missed appointment. The complexity of problems across physical and psychosocial health, and interpersonal and behavioural difficulties, combined with the difficulties in organising multiple agencies, placements and movement across regional boundaries can challenge the most dedicated clinicians. This has contributed to a situation in which the most vulnerable and needy young people receive the least care.32

Conclusion

The recommendations in the National Framework focus on the development of safety, trust, choice, collaboration and empowerment in the relationship between doctor and patient, as well as on the importance of the involvement of carers. Communication among multiple care providers is essential to maintain continuity of care. The National Framework also promotes a communication loop of reliable and timely feedback between GPs or other members of the general practice team, the young person, carers, family of origin and their care team.33 While enactment of these recommendations can be viewed as time-consuming and difficult, developing such relationships can ultimately save time, and are necessary if we are to provide effective healthcare to this group.

Authors

Kristen Moeller-Saxone PhD, Project Manager – Ripple Out of Home Care Project, Bounce Project, Orygen, National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic; Research Fellow, Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic

Louise McCutcheon DPsych, MAPS, Orygen, National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic; Centre for Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic; Senior Program Manager, Orygen Youth Health, Northwestern Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic

Stephen Halperin BSc, BPsych MAP (Clinical), Senior Psychologist, Orygen, National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic; Leader Youth Mood Clinic, Orygen Youth Health, Northwestern Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic

Helen Herrman MD, MBBS, BMedSc, FFPHM, FRANZCP, FAFPHM, Professor, President-elect, World Psychiatric Association; Director, Orygen, National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic; Centre for Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic

Andrew M Chanen MBBS (Hons), BMedSci (Hons), MPM, PhD, FRANZCP, Deputy Research Director, National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic; Professorial Fellow, Centre for Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic; Orygen Youth Health, Northwestern Mental Health, Melbourne, Vic. andrew.chanen@orygen.org.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.