A career in general practice can be likened to a dynamic pipeline of decision making.1 Developing a sense of identity and finding fulfilment is central to the process of becoming and remaining a general practitioner (GP).1,2 Mentoring a medical student in your practice can be a satisfying long-term experience that is mutually beneficial for both parties.3 Medical students seek passionate mentors4,5 who are positive role models and assist the students in their own problem-solving in the early stages of their career. A in any caring relationship, the mentoring relationship can present challenges for mentor and mentee.6,7 Considering these issues in advance will assist with successfully mentoring a medical student in your practice.

The aim of this article is to define mentoring and the roles of mentor and mentee in Australian general practice. Practical suggestions are made on how to structure a mentorship program in your practice.

What is mentoring?

Mentoring within the practice can occur informally when a GP is approached by an interested medical student8 or via formalised programs such as the Rural Australia Medical Undergraduate Scholarship9 and John Flynn Scholarship programs.5 Mentoring is a long-term relationship between an experienced GP and the student, based on shared professional and personal interests.10 It is a caring and supportive relationship outside the formalised course of the university environment.7,9 In this context, it differs from shorter term medical placements of the medical course. However, there are exceptions to this relationship.

Some universities have developed mentoring roles as part of their formal course. An example is the longer rural clinical placements offered by rural clinical schools of many Australian universities. Students often rotate between hospital, general practice and the community in these placements.11,12 Mentors are identified as positively fostering an interest in rural medicine by medical students in these programs.11 When mentors become involved in the formal undergraduate course, they need to be clear on their role. This is particularly true if the university asks the mentor to be involved in summative assessment. This dual role can impair the caring, supportive relationship of the traditional mentor.

Clarifying the supervisor’s and student’s roles is important to the success of mentoring in any of these settings, whether formal or informal. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) considers mentoring to be an important role for GPs. It differs13 in function from leadership and teaching. Leadership is the demonstration of positive professional attributes and its promotion, in this case, to medical students. Teaching can be short term or long term, with specific learning goals and aims, delivery, assessment and evaluation. It can be didactic or focused on the learner.14 Benjamin Franklin eloquently described this difference in describing the leader (role model), teacher and mentor respectively:15

Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.

Rather than solving a mentee’s problems, the mentor’s role is to provide a confidential, trusted space to allow the mentee to solve problems, often balancing their own professional and personal needs. This requires defining the problem, setting goals, planning, learning and reflecting on achievement.8 Sustainable general practice requires balancing the demands of GPs’ professional and personal lives with self-care and having one’s GP being central to this process.16 Both mentors and students should have their own GP. A positive mentor demonstrating sustainable practice over a period of time offers a powerful learning experience likely to encourage more students to enter rural practice.5

Mentoring has a variable meaning based on the lived experiences and actions of the mentor and mentee.10 Most4 medical students will want to explore career counselling, acquiring educational skills and knowledge needed for practice,17 professionalism and personal issues. An effective mentor needs to be available on a regular basis, non-judgemental, encouraging, providing role modelling and professional networks, and assisting in the medical student’s personal and professional development.4 Time needs to be allocated to the mentoring relationship.7 Mentors can benefit from the relationship, gaining career satisfaction and personal gratification.3

Forming a mentorship

The literature is divided on whether medical students should be matched on the basis of factors such as gender and minority groups in their mentoring relationship. In some studies, female students2,18 and students with overseas backgrounds19 value the guidance of mentors who are female and/or from their country of origin respectively. It is more important, however, that the mentor is an experienced GP,20 develops rapport with the student, is positive about general practice20 and is respectful and mindful of differences concerning gender and background.4

Confidentiality is central to the mentoring relationship. The key to a long-term mentoring relationship is defining roles and obligations at the start, and revisiting these periodically as an interactive process between mentor and mentee.7,8 Learning will be more powerful in the mentoring relationship if the mentee is proactive and responsible for planning meetings and the agenda.4,8

Confidentiality in any caring relationship may at times be challenged. Notification to the Medical Board of Australia of a medical student whose impairment places the public at risk is now mandatory.21 Mentors dealing with a stressed student can experience stress themselves and may require their own mentor.7 If handled well, the mentor can offer the student a safe environment to access assistance in a non-threatening way, hopefully assisting them to continue in their medical career and developing resilience.

Mentors need to avoid two factors in order to facilitate the development of a safe, trusted environment. First, the mentor needs to avoid summative assessment of the medical student. Knowledge of a student’s professional and personal life means that an objective assessment will be, or be perceived to be, invalid when a mentor conducts a high-stakes barrier exam. Blurring of summative assessment and mentoring roles can result in situations where the mentor has been described as a ‘tormentor’ by disempowered doctors in training.6 Furthermore, the knowledge that the assessor may be aware of personal information is seen as a significant barrier to a successful mentoring relationship by junior doctors.20

Second, the mentor’s role is to be a safety net for a medical student at risk. Knowing the medical student’s personal and professional background can reduce the mentor’s objectivity. The mentor needs to avoid treating an impaired medical student and/or

doing work on their behalf. The student may need assistance to access a GP skilled in treating medical colleagues.

Structuring mentoring in your practice

An open-ended question such as, ‘How are you going?’7 may be all that is needed for setting the agenda for a mentoring session. However, providing structure to the mentoring session will assist. Box 1 provides some prompting questions that may assist the interaction. Alternatively, giving the student the responsibility of setting an agenda should be considered. This will provide a richer learning experience as it includes skills in negotiating with their mentor.8 These skills in dealing with more experienced clinicians can be important in the workplace after graduation.8 Enthusiasm from students and mentors will foster a rewarding, sustainable mentorship.3,8

Box 1. Possible trigger questions to think about and discuss in the mentorship

|

|

What knowledge and skills do you want or need to develop as part of your mentorship?

Where do you think your strengths and weaknesses are?

What are your long-term goals? How can we assist in this process?

What particular opportunities exist in this practice to develop your clinical skills?

How confident do you feel in particular areas?

How do you manage time as a medical student?

How do you balance your personal and professional life at this stage of training?

What challenges have you faced recently?

|

An initial face-to-face meeting needs to be conducted in a safe environment with allocated time. It is important to avoid situations or venues where claims of unprofessional behaviours from either party could arise. A neutral location such as a coffee shop away from the clinical setting will reduce interruptions and may make the student more comfortable, particularly if they want to discuss confidential matters. Ongoing contact, either by phone or email, should be arranged between face-to-face sessions to ensure student wellbeing.

Box 2. Sources of information in general practice to base

a formative assessment

|

|

Personal observation

Case discussion during mentoring sessions

Medical student presenting a case

Feedback of practice patients

Impressions of receptionist or practice nurse

Acquisition of skills and progress

Progress documented in learning plan

|

While our role as mentor should avoid being summative, our medical students crave formative feedback.4 They often ask questions about their competence and progress. Box 2 lists areas in which a mentor may consider providing formative feedback, which needs to be specific, timely and linked to behaviours. Generalised feedback such as ‘I think you are going well’ does not provide specific feedback and is unlikely to help the student. Instead, more useful and specific feedback would include, for example, ‘The thing I believe made your case presentation particularly impressive was the patient-centred insight you gained about managing chronic illness in a small community’.

To date, most of the literature on feedback has been written from a teaching and learning background, with learner exploration and reflection assisted by the supervisor. Examples include the work of:

- Pendleton et al22 – providing positives prior to negatives, with learner issues explored initially

- vanWeel-Baumgarten et al23 – using the process of a consultation and its content to explore communication skills and learning

- Moorhead et al24 – providing a broad overview of feedback in Australian general practice and adult learning.

With the expansion of mentoring in medical education, there is a need to evaluate frameworks of feedback and learning best suited to a mentoring relationship. In the absence of this exploration, by necessity, this article argues that the mentor will need to use medical education pedagogy to optimise the mentorship experience for their students.

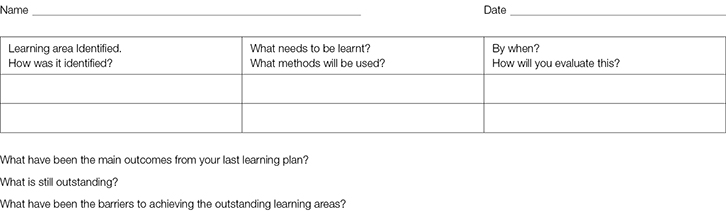

Longer term placements lend themselves to planned learning in the clinical domains, personal and professional development, and cultural training, which can increase the preparedness of medical students for practice.12 Additionally, mentees can develop competency in a number of skills that will assist in the day-to-day running of the practice. For example, students under supervision can be taught to clerk some patients and conduct simple procedures before they are seen by their supervising GP.12 Breaking a complex procedure into a number of learning skills and stages on the basis of the medical student’s experience and progress assists in skills acquisition.25 There may be a role for mentees to talk to high school students or junior medical students to inspire more to consider a career in general practice.1,5 Developing a learning plan between student and mentor for the mentorship will assist in setting goals, planning learning and assessing progress. This can be formalised, as in Figure 1, or an informal agreement in the mentorship. This can form the basis for setting agendas of contact meetings.

|

| Figure 1. Learning plan |

Orientating medical students to the practice will assist them to develop a sense of belonging. Patient-centred care is influenced by an understanding of the services and resources available in a work environment. An example from rural practice that could be applied in any setting is the ARTS (assessment, resources, transport and support) process developed by McConnel et al.26 ARTS is about translating best practice and evidence in a setting on the basis of available resources (Box 3).

Box 3. Orientation of the mentee to the practice and community

|

|

Patient-centred care in general practice is complex and based on environmental factors such as the following:26

Assessment of the patient:

- Complexity

- Socioeconomic

- Cultural and psychological

- Public health

Resources availability:

- Human (other members of the health team)

- Advice

- Technical and equipment

Transport

Support

- Psychological and professional

- Management and organisational

This needs to occur in the context that each health professional is part of a larger team.

|

Conclusion

Mentoring a student in your practice can be a rewarding experience for mentor and mentee. Providing medical students with a safe, reflective environment will assist them to gain the skills for lifelong, sustainable practice. Hopefully, with time, these students will go onto to train and mentor the next generation of GPs in the workforce pipeline.1 To date, much of the medical literature on mentoring has focused on short-term evaluation. More research is needed to assess the longer term impact and cost-effectiveness of mentoring medical students in general practice and other settings.3,4 There is a need to develop and evaluate methods for feedback and learning in mentorship. This will avoid the pitfall of mentors undermining the mentorship process by blurring this role with that of teacher or assessor undertaking summative assessment on their students.

Author

John Fraser MD, FRACGP, FAFPHM, FACRRM, FACTM, Dip RACOG, MBBS (Hons), Adjunct Professor, School of Rural Medicine, University of New England, Armidale, NSW; General Practitioner, Manilla, NSW. jfrase22@une.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed.