Case

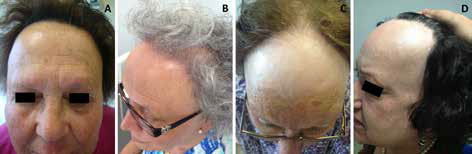

Four women aged 68 (Patient 1, Figure 1A), 74 (Patient 2, Figure 1B), 70 (Patient 3, Figure 1C) and 76 years (Patient 4, Figure 1D) presented with progressive hair loss affecting the frontotemporal area that had been developing for approximately 10, 8, 5 and 12 years, respectively. All four patients also presented with loss of eyebrows. The skin in the affected area was pale in Patients 3 and 4, and shiny and wrinkle-free in all four women. Close inspection revealed mild erythema and scaling around the hair follicles at the margins of the bald areas. In Patient 2, a diffuse thinning of hair over the crown was noted.

|

| Figure 1. Clinical appearance of the patients |

|---|

Question 1

What is the most likely diagnosis in these patients?

Question 2

How would you diagnose this condition?

Question 3

What differential diagnoses would you consider?

Question 4

What therapeutic measures would you recommend?

Answer 1

The diagnosis in all of these presentations is frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), an acquired cicatricial (or scarring) alopecia characterised by recession of the frontotemporal hairline, which predominantly affects postmenopausal women.1 It is considered a clinical variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP) as the histological findings are similar. Other variants are classic LPP and Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome.1 The exact pathophysiology of FFA is unknown. A possible cause is the disturbed immune response to a component of the intermediate-sized and vellus scalp hair follicles.2 Another possibility that remains under debate is a hormonal cause. This hypothesis is supported by the strong association with postmenopausal onset and the occasional improvement with anti-androgen therapy.3,4 However, there is no association with hormonal abnormalities and no response to hormone replacement therapy.5,6 In addition, FFA rarely affects men or premenopausal women.7

Answer 2

FFA is a primary scarring alopecia that usually affects the frontotemporal hairline as an asymptomatic symmetrical and progressive band of hair loss, often accompanied by eyebrow loss.5,8 The hairless skin may be pale, smooth, atrophic and shiny with destruction of the follicular openings.2,6,7 The hairline recession may seem moth-eaten and a few remaining hairs may persist in the alopecic areas.2 Sometimes, clinical features of LPP, such as inflammatory papules and follicular or perifollicular erythema, can be found, particularly in the initial stages of FFA.6 Progression is unpredictable, but generally alopecia progresses slowly and stops spontaneously a few years after onset.2,7 Some women with this condition also have female androgenic alopecia, as observed in Patient 2.6

A skin biopsy is helpful in making the diagnosis. The histopathological features are identical to those of LPP and include destruction of hair follicles by an inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate and perifollicular lamellar fibrosis, which are localised around the upper portion of the hair follicle.1,7,9 Therefore, FFA is considered a primary lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia.1

Answer 3

Conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis of FFA are listed in Table 1. A clinical history and physical examination, including the distribution pattern of the alopecia, the involvement of other hairy areas and the existence of other cutaneous manifestations, may be enough to differentiate some of the conditions. However, skin biopsy for histological examination can be necessary.6

Table 1. Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of frontal fibrosing alopecia1,7,8

|

Disease

|

Differentiating features

|

|---|

|

Scarring alopecia

|

Lichen planopilaris

|

Multifocal alopecic plaques in the scalp

Lichen planus lesions in other locations, including the skin, mucous membranes, and nails

|

|

Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome

|

Multifocal alopecic plaques in the scalp

Non-scarring alopecia of the axillae and/or groin

Keratotic follicular papules on trunk and limbs

|

|

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus erythematosus)

|

Solitary or multiple alopecic plaques showing active inflammation, scaling, follicular plugging and atrophy with variable degrees of telangiectasia and dyspigmentation

Can be sensitive, itchy and worse after UV exposure.

Other manifestations of DLE or systemic lupus erythematosus; antinuclear antibodies can be positive

Histology: lymphocyte-mediated interface dermatitis that shows basilar vacuolar degeneration and a thickening of the basement membrane

|

|

Pseudopelade of Brocq

|

Often begins on the parietal scalp

Small flesh-toned alopecic areas with irregular margins (‘footprints in the snow’)

Typical absence of follicular hyperkeratosis and erythema

|

|

Non-scarring alopecia

|

Alopecia areata, ophiasis type

|

Occurs in both sexes and at any age

Non-inflammatory band-like pattern of hair loss along the periphery of the temporal and occipital scalp, presence of exclamation mark hairs and preservation of follicular orifices

May be associated with other autoimmune diseases (thyroid disease, coeliac disease, vitiligo and atopy) and nail abnormalities

Histology: lymphocytic infiltrate around the peribulbar area

|

|

Female pattern hair loss (female androgenic alopecia)

|

Diffuse central thinning of the crown with preservation of the frontal hairline. Does not cause eyebrow loss. Hair miniaturisation is the typical finding

Normal levels of androgens in blood in most cases

Histology: follicular miniaturisation and minimal inflammation

|

Answer 4

FFA is an irreversible process. Therefore, our aim should be to prevent disease progression. At present, there are no therapeutic options that have proven to be effective with an appropriate level of evidence.5 Treatments that have been used include corticosteroids (topical, intralesional and systemic), 5-α reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride), topical minoxidil, antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine) and antibiotics.3,5,6

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line therapy, mainly in the early inflammatory stages. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (1 mg/cm2 every 3 months using a solution of 20 mg/mL for scalp and 2 mg/mL for eyebrows) is a possibility. However, it may worsen fibrosis and atrophy in advanced stages.6 In rapidly progressive cases, oral antimalarials, mainly hydroxychloroquine, may be used.2 Antibiotics such as tetracyclines, finasteride and topical minoxidil are other possible choices.2,5 Other treatments that have been used, although with no evident benefits, include retinoids, calcineurin inhibitors, griseofulvin or hormone replacement therapy.6 There is little experience regarding the outcome of hair transplantation in FFA. However, some studies suggest that long-term results can be disappointing, and all potential patients should be advised of the possibility of hair graft loss over time.10 A wig or hairpiece, or the use of hair bands and clever hairstyling that disguise the frontal hair loss, may be recommended.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.