More than 500 000 encounters were recorded in BEACH over the study period and 12 380 of those encounters were with patients who had a repatriation health card. Half of these veterans (50.2%) were aged 85 years or over and another 26.1% were aged 75–84 years. One in five (19.8%) were 55–74 years and almost 4% were 18–54 years. Males accounted for 48% of the sample. We analysed patients by these age and sex groups.

PTSD management rates

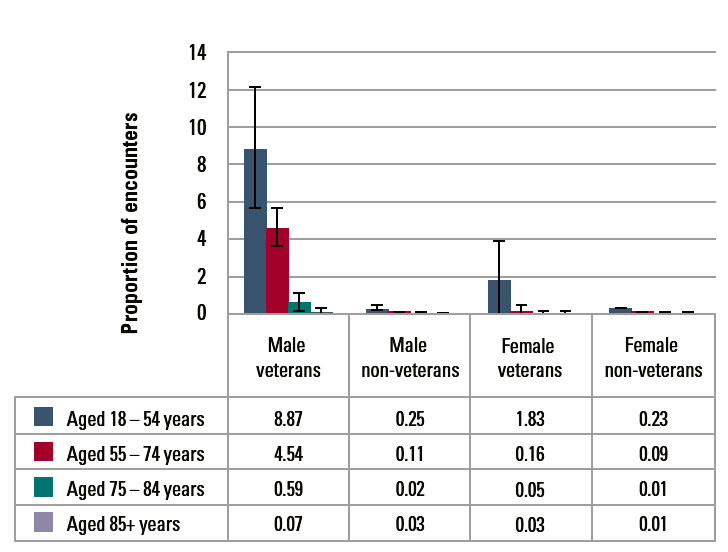

PTSD was managed at 8.9% of encounters with male veterans aged 18–54 years, which was significantly more often than at encounters with non-veterans (0.3%). The same result was found for males aged 55–74 years (4.5% compared with 0.1%) and those aged 75–84 years (0.6% for veterans and 0.02% for non-veterans). A similar trend was seen for the younger female veterans, but the sample size lacked enough power to reach significance (Figure 1).

|

|

Figure 1. Proportion of GP encounters where PTSD was managed: veterans and non-veterans

|

|---|

|

Our sample of veterans is of necessity limited to those who hold a repatriation health card. The card is issued by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs to former members of Australia’s defence force and their dependants who are deemed ‘entitled to treatment’, and to all veterans aged 70 years and over.2 This will have affected the age distribution reported here. Also, the higher attendance rates among elderly patients in general may have lessened the relative rate of PTSD management found in the older age groups.

Our findings agree with past studies showing that Vietnam veterans (those aged 55–74 years) have elevated levels of PTSD.3 The high rate among veterans in the 18–54 age group, which includes men and women who have served in the Middle East and Afghanistan, should be kept in mind by general practitioners when managing veterans’ health.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the GP participants in the BEACH program and all members of the BEACH team. Financial contributors to BEACH 2009–2014: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs; Abbott Australasia Pty Ltd; AstraZeneca Pty Ltd (Australia); Bayer Australia Ltd; CSL Biotherapies Pty Ltd; GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd; Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd; Merck, Sharp and Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd; National Prescribing Service Ltd; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd; Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd; Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd; Wyeth Australia Pty Ltd.