Rosacea is a chronic cutaneous condition characterised mainly by facial flushing and erythema. Persistent erythema in the central portion of the face lasting for at least three months is the primary feature of rosacea.1 Other characteristic findings that are often present, but not needed for diagnosis, include flushing, telangiectasia, oedema, inflammatory papules, pustules, ocular symptoms and rhinophyma or hyperplasia of the connective tissue.1–3 These findings help determine the subtype of rosacea. Although rosacea is largely a cosmetic issue, it can significantly affect a patient’s self-esteem.1

Rosacea most commonly affects those with fair skin, blue eyes, and those of European or Celtic origin.1 However, patients of any ethnic group may be affected. While flushing may start as early as in childhood,5–7 symptoms of rosacea typically peak from ages 30 to 50 years. Rosacea is more common in females than males; however, males develop phymatous rosacea more frequently.1–3 A Swedish study reported the incidence of rosacea to be 10%,1 while a UK study reported an incidence ranging from 0.09% to 22%.2

Pathophysiology of rosacea

The aetiology of rosacea comprises a number of factors, which are detailed below. Often, these factors overlap.

Genetic vascular reactivity

Rosacea is thought to have a genetic component, with a higher incidence found in fair-skinned individuals of Celtic or northern European descent.3

Genetic vascular reactivity results in increased blood vessel density near the skin surface. Increased blood flow to the facial vasculature then leads to flushing or transient erythema. This is controlled by vasodilatory mechanisms.4

There are a number of factors that may trigger flushing in rosacea, including harsh climate, extreme temperature, solar radiation, emotion, spicy food, alcohol and hot beverages (Box 1).13

Demodex mites

An association between Demodex follicularum and rosacea has been reported. D. follicularum is a mite that lives in sebaceous follicles. In vitro investigations have found that D. follicularum has antigens that react with sera from patients with rosacea, and are capable of stimulating mononuclear cells to proliferate.5 Patients with rosacea have more mites in the follicles around the nose and cheek, compared with other patients,5,6 and these often have a surrounding inflammatory response.7 Studies have shown that treatment of Demodex mites with topical ivermectin improves inflammatory rosacea.5–7

Cathelicidin

Patients with rosacea have elevated epidermal serine protease activity, which causes the deposition of cathelicidin-derived peptides in the skin.8 These are pro-inflammatory peptides. Abnormal skin barriers often show elevation of serine proteases. The level of serine proteases normalises when the skin barrier is restored.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical presentation for rosacea is varied. There are four primary subtypes – erythrotelangiectatic (ETR; also known as vascular), inflammatory (also known as papulopustular), phymatous and ocular. There are also rarer variants, such as granulomatous rosacea, pyoderma faciale and oedematous rosacea. Determining the subtype enables the clinician to choose the correct therapy.

Erythrotelangiectatic (vascular) rosacea

ETR is characterised by flushing and vasodilation and, over time, this leads to the development of permanent erythema, then telangiectasia on the affected areas. Usually, the central area of the face is most affected,9 although, the ears, neck or upper chest can also be affected.10 Common triggers of flushing are listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Triggers associated with worsening rosacea symptoms1

|

Trigger

|

|---|

|

Emotional stress

Hot or cold weather

Sun exposure

Wind

Exercise

Hot drinks

Alcohol consumption

Spicy foods

Dairy products

Hot baths or showers

Certain skin care products

Certain cosmetics

Medications (eg topical steroids, niacin, beta blockers)

|

Box 2. General measures for rosacea3,9,22

|

General measures

|

|---|

|

Inform patient of chronic, intermittent and inflammatory nature of rosacea

|

|

Identify factors that trigger patient’s signs and symptoms

|

|

Encourage patient to keep a journal documenting exposures, diet and activities that cause flare-ups

|

|

Daily use of broad-spectrum sunscreen, avoidance of midday sun, shade, protective clothing

|

|

Soap-free and abrasive-free cleansers

|

|

Moisturisers should be used if the skin is dry

|

|

Avoid use of abrasive materials and pat dry for better absorption of moisturisers

|

|

Cosmetics with green or yellow tint applied to the central face may conceal redness

|

|

Topical corticosteroids are relatively contraindicated on the face

|

Papulopustular rosacea

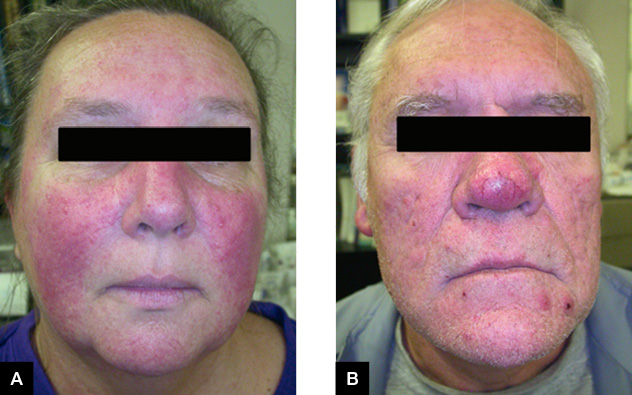

Papulopustular rosacea (PPR), also known as inflammatory rosacea, is characterised by persistent or episodic development of inflammatory papules and pustules, often on the central face. There may be background ETR. Patients are typically middle-aged women (Figure 1A).2

Phymatous rosacea

Phymatous rosacea is characterised by hyperplasia of skin because of chronic inflammation. The most commonly affected area is the nose, leading to rhinophyma. (Figure 1b). This subtype of rosacea occurs mostly in older men. In addition, significant telangiectasia can also often present over the affected regions.

Figure 1A. Erythrotelangiectatic rosacea overlapping with papulopustular rosacea

Figure 1B. Phymatous rosacea with the characteristic skin thickening, irregular surface and bulbous nose

Ocular rosacea

Ocular manifestations of rosacea often precede the development of cutaneous signs, but can also occur concurrently. Ocular rosacea primarily affects adults, but occasionally may also affect children. It can affect males and females alike.1,12 Blepharitis and conjunctivitis are the most common findings.13 In some cases, ocular rosacea may also be associated with corneal damage.13 In severe cases, assessment by an ophthalmologist is recommended.

Differential diagnosis

There are many skin conditions that share similar features to those of rosacea. These conditions may overlap with rosacea.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis presents with scaling and erythema, often on the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, scalp and pre-sternal areas. ETR can resemble seborrhoeic dermatitis, which, in fact, can co-exist with rosacea (seborosacea).

Periorofacial dermatitis

Periorofacial dermatitis usually presents with inflammatory papules around the mouth, eyes and nasal area. This is often caused by the prolonged use of potent topical corticosteroids on facial skin.

Acne

Acne vulgaris is typically seen in the younger age group, and is characterised by comedonal lesions, papules, pustules and cysts, often on the face, but some acne may affect the back and chest. Some acne lesions also cause scarring. Patients in their 20s and 30s may experience rosacea and acne simultaneously.

Keratosis pilaris

Keratosis pilaris is a facial disease that can be difficult to differentiate from rosacea, and may occur in patients simultaneously. It is characterised by a fixed blush appearance, especially on the lateral cheeks, with fine follicular keratotic plugs. Keratosis pilaris is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and can also affect the posterior surface of the arms and the anterior thighs.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experience a malar erythema, which is difficult to differentiate from rosacea. SLE is characterised by photosensitivity, pigment change, follicular plugging and scarring. The presence of systemic disease, such as arthritis, will also favour a diagnosis of SLE.

Treatment

Rosacea is managed mainly with general measures (Box 2) and treatments targeted at the specific presenting symptoms (Table 1). The goals of pharmacotherapy for rosacea are to reduce morbidity and symptoms, and achieve disease control, as rosacea is not curable.

Systemic treatment

Oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics reduce the inflammatory lesions, such as papules and pustules, as well as the ocular symptoms of rosacea. They are usually prescribed for 6–12 weeks, and this can be variable, depending on the severity of the rosacea.

Doxycycline 50–100 mg once daily is recommended as initial oral therapy.14 Further courses may be required, as inflammatory rosacea is chronic and often recurs. Use of a sub-antimicrobial dose of doxycycline avoids the development of bacterial resistance while enhancing safety and tolerability.15 Adverse reactions of doxycycline that patients need to be made aware of include photosensitivity, Candida vaginitis, pill oesophagitis and diarrhoea.

Alternative antibiotics include minocycline, erythromycin, cotrimoxazole or metronidazole. Anti-inflammatory effects of antibiotics aid in the overall reduction of inflammation associated with rosacea.14

Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin, prescribed by a specialist dermatologist, is used for the management of refractory papulopustular and phymatous rosacea.16 When antibiotics are ineffective or poorly tolerated, isotretinoin may be very effective. When used in the treatment of rosacea, the dosage is usually small (10–20 mg/day) and for a duration of four to six months. Although the mechanism by which isotretinoin is effective is unclear, inflammatory lesions and refractory nodules typically respond well to isotretinoin.13 Isotretinoin is also useful for preventing the progression of rhinophyma, and the best results are achieved if treatment is commenced before significant fibrosis has developed.13

Topical treatment

Metronidazole and azelaic acid

Topical agents are first-line therapy in the treatment of mild‑to‑moderate rosacea. For mild rosacea, it is recommended to use metronidazole cream or gel intermittently or long term. For more severe cases, antibiotics should be added to this regimen.

Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of topical metronidazole have demonstrated beneficial effects.17 Metronidazole reduces oxidative stress. In Australia, metronidazole 0.75% gel and cream are available. Adverse effects, including pruritus, irritation and dryness, are mild.18

Azelaic acid is also helpful. Randomised controlled trials have also shown effectiveness in the use of 20% azelaic acid lotion and 15% gel in reducing inflammatory lesions.15

Ivermectin

Ivermectin cream is used to control Demodex mites. Ivermectin 1% cream has been shown in randomised controlled trials to be effective.15,19

Brimonidine

Brimonidine (eg Mirvaso) is shown to be effective in the treatment of ETR. In Australia, it is used in gel form (0.5%) and acts as an alpha adrenoceptor agonist to reduce erythema temporarily. Adverse effects include irritation, burning, dry skin, pruritus and erythema.17

Vascular laser therapy and intense pulsed light

Vascular laser therapy specifically targets haemoglobin in vessels, and hence, effectively treats facial erythema and telangiectasia. Laser treatment is generally not as effective for the treatment of papulopustular lesions. Intense pulsed light (IPL) has also been reported to be effective in the treatment of rosacea. Adverse effects of IPL, which patients must be informed about, include blistering purpura, rarely loss of pigmentation, ulceration and scarring. IPL and vascular laser treatment are not curative; recurrence is the norm and intermittent re-treatment is often necessary.

Specific measures for phymatous rosacea

Phymatous rosacea can be disfiguring and difficult to treat. Results have been more effective in patients who are treated early. Oral isotretinoin is used to reduce nasal volume in early disease; however, after discontinuing the medication, recurrence is often seen. Unfortunately, mucinous and fibrotic changes are unresponsive to isotretinoin.10 Mechanical dermabrasion, ablative laser resurfacing and surgical shave techniques may produce cosmetic improvement of rhinophyma.10

Table 1. Management of rosacea2,3,8,14

|

Central facial erythema without papulopustular lesions

|

Central facial erythema with papulopustular lesions

|

Phymatous

|

|---|

|

|

Mild-to-moderate

|

Moderate-to-severe

|

|

|

General measures

|

Begin with a mild non-alkaline skin cleansing and moisturising routine

Avoid abrasives and fragrances (eg alcohol, acetone)

Use broad-spectrum sunscreen, SFP 30 or greater

Educate on trigger avoidance

|

Begin with a mild non-alkaline skin cleansing and moisturising routine

Avoid abrasives and fragrances (eg alcohol, acetone)

Use broad-spectrum sunscreen, SFP 30 or greater

Educate on trigger avoidance

|

Same as mild-to-moderate

|

Trigger avoidance

Photoprotection

|

|

First-line therapy

|

Topical metronidazole (eg Flagyl, Metrogel) for inflammatory lesions or brimonidine (eg Mirvaso) for erythema

Azelaic acid also advised as an alternative for inflammation

|

Topical metronidazole for inflammatory lesions

Topical brimonidine for erythema if needed as adjunctive therapy

Topical ivermectin for inflammation; may be used in combination with metronidazole

|

Topical metronidazole for inflammation plus anti‑inflammatory dose of doxycycline (50–100 mg daily)

Topical brimonidine for erythema if needed as adjunctive therapy

|

Mid-to-high dose isotretinoin for 12–28 weeks

Microdose therapy for maintenance

Topical and/or oral antimicrobials as needed for inflammatory lesions

|

|

Second-line therapy

|

Vascular laser therapy (eg pulsed dye laser, intense pulsed light) for erythema and telangiectasia

|

Sub-antimicrobial (anti‑inflammatory) dose doxycycline (50–100 mg daily)

Vascular laser therapy for erythema and telangiectasia

|

If limited or no response at 8–12 weeks, consider antimicrobial dose of doxycycline (100–200 mg daily)

Vascular laser therapy for erythema and telangiectasia

|

Vascular laser therapy

|

|

Third-line therapy

|

|

If limited or no response at 8–12 weeks, consider antimicrobial (antibiotic) dose of doxycycline (100–200 mg daily)

|

If limited or no response, consider alternative oral antibiotic (eg metronidazole, azithromycin)

|

Ablative laser treatment, dermabrasion, surgical debulking

|

|

Refractory

|

|

Systemic isotretinoin

Consider treatment in the moderate-to-severe category

|

If refractory to treatment consider oral isotretinoin

|

|

Conclusion

Rosacea is a common, chronic problem. The subtype of rosacea and its associated clinical features determine which therapeutic modalities a clinician will use. Often, patients require a combination of therapies for effective treatment, as different subtypes co-exist, and because of the recalcitrant and persistent nature of rosacea.

Authors

Danit Maor MBBS, Research Fellow, Skin and Cancer Foundation Inc, University of Melbourne, Vic

Alvin H Chong MBBS, MMed, FACD, Senior Lecturer, Skin and Cancer Foundation Inc, University of Melbourne alvin.chong@svha.org.au

Competing interest and funding: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, internally and externally peer reviewed.