Case

A woman, 70 years of age, presents to her general practitioner (GP) and mentions in passing that she has had some memory loss. Her GP excludes common causes of memory problems, such as depression or urinary tract infection, and asks the practice nurse to perform a mini-mental state examination (MMSE). The patient scores 25, which is close to but above the cut-off point for probable dementia, which would trigger further investigation. The GP decides to take a watch-and-wait approach, assuring her that this is not unusual for her age. No medication review is undertaken.

The GP sees the patient every few months for routine medical care, and the patient denies any further memory or functional problems. The GP assumes that she has some degree of cognitive impairment, but is functioning reasonably well. No further cognitive function test is performed as the patient is below the age for the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) rebatable 75+ health assessment, which may include cognitive function testing in those with symptoms.

After a number of years, the patient’s daughter presents to the GP and explains that she has been increasingly involved in her mother’s care and is concerned about her mother’s memory loss, confusion, anxiety and difficulty managing self-care. It becomes apparent that the patient has developed dementia, but the GP was unaware of the extent of her symptoms within the community. The daughter expresses that she no longer feels able to care for her mother, given her mother’s difficult moods and behaviour, and asks for advice on the process for admission to residential care.

The case presented is a familiar scenario in Australian general practice. In this country, almost one in 10 people aged 65 years and older has dementia.1 Most people with dementia (84%) first report symptoms to their GP,2 but a delay between the appearance of symptoms and diagnosis of dementia is common.1 It is estimated that 50% of people with early dementia are not diagnosed when presenting to primary care.3–5

The Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre’s Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia (Guidelines) was approved by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in February 2016.6,7 The Guidelines were developed by adapting the UK’s guidelines for dementia8,9 by a committee of experts in dementia, including carers of people with dementia and a GP. The Guidelines were released for public consultation and were reviewed by many medical colleges, including The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP).

The scope and target audience of the Guidelines are broad. This article summarises the recommendations that are most relevant to GPs. They are identified as practice points (PPs), consensus-based recommendations (CBRs) or evidence-based recommendations (EBRs). CBRs are those formulated when a systematic review of available evidence did not identify high-quality evidence to inform the recommendation. PPs were outside the scope of the systematic reviews and were based on expert opinion. Quality of evidence was determined using the grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) approach10 and indicates the confidence in the effect estimate and how likely further research is to have an important impact. Key evidence-based recommendations for GPs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Key evidence-based recommendations for implementation by GP, formulated following systematic review of the available evidence

|

Recommendation type

|

Guidance

|

|---|

|

EBR (low)

|

Offer referral to memory assessment specialists or services

|

|

EBR (low)

|

Occupational therapy interventions, including assistive technologies, tailored interventions to improve independence, and environmental assessment and modification are useful for those living in the community

|

|

EBR (low)

|

Exercise is important for people with dementia; if appropriate, refer to a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist

|

|

EBR (low)

|

The impact of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia can be reduced by providing person-centred care (care that is consistent with the 10 principles of dignity in care)

|

|

EBR (low)

|

Carer(s) and families of a person with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia should be offered training in communicating effectively, managing symptoms, management planning, activity planning, problem solving, and environmental modifications

|

|

EBR (very low to low)

|

People who develop behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia should be offered involvement in meaningful activities that are individually tailored and, ideally, multicomponent. Individual activities that have evidence of benefits include music and/or dancing, support and counselling, and reminiscence therapy for depression and/or anxiety; and behavioural management, music and/or dancing, massage or reminiscence therapy for agitation

|

|

EBR (low)

|

If an observational pain assessment tool indicates a person with dementia is likely to be in pain, analgesic medication should be trialled for a set time period in a stepwise manner

|

|

EBR (moderate)

|

The role of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in people with dementia is uncertain. Nevertheless, people with dementia with a history of major depression (prior to developing dementia) who develop comorbid major depression should be treated in the usual way

|

|

EBR (moderate)

|

Antipsychotic medications should not usually be prescribed to people with mild-to-moderate behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia because of the increased risk of cerebrovascular adverse events and death

|

|

EBR (moderate)

|

People with severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (ie psychosis and/or agitation/aggression) causing significant distress to themselves or others, may be offered treatment with an antipsychotic medication if the following is followed:

- Discuss the benefits and risks openly with the person with dementia, their carers and family, assessing cerebrovascular risk factors and considering the possible increased risk of stroke/transient ischaemic attack and adverse cognitive effects

- Clearly document the target symptoms

- Consider the effect of comorbidities, including depression

- An individual risk–benefit analysis should inform the choice of antipsychotic

- Commence with a low dose and titrate as necessary

- Carefully monitor for side effects including metabolic syndrome

- Discontinue treatment within one to two weeks if not efficacious

- Conduct assessment, recording any changes in symptoms and cognition at 4–12 week intervals, considering whether ongoing treatment with antipsychotics is necessary

|

|

EBR, evidence-based recommendation

|

Diagnosis

Although there is often a lengthy gap between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of dementia,11,12 the Guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence on the relative benefits and harms to support general population screening (CBR).13 Nevertheless, GPs should look out for symptoms of cognitive decline, particularly in those aged ≥75 years (CBR), and investigate symptoms when they are first raised (PP; Figure 1).

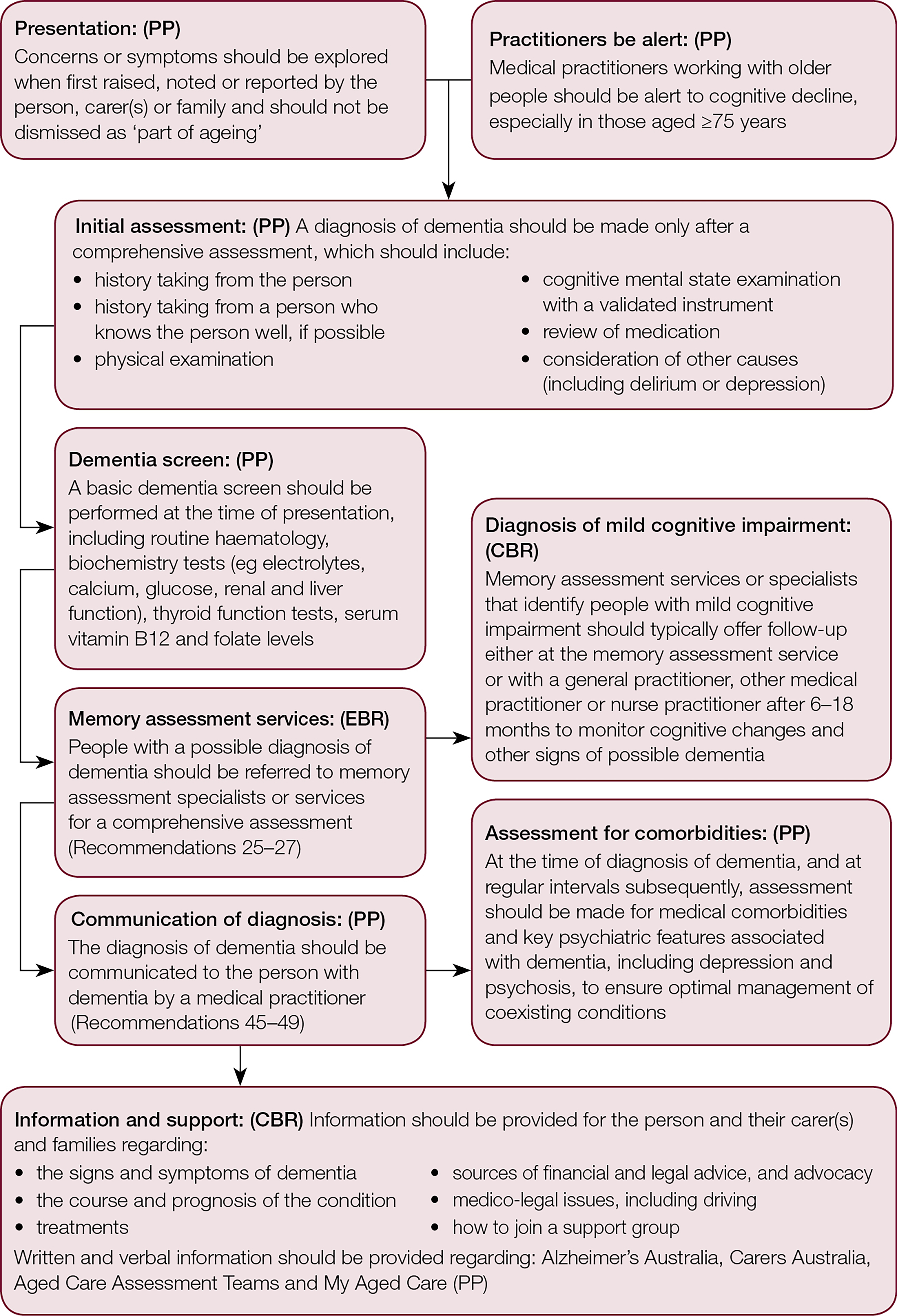

Figure 1. The assessment process for dementia diagnosis

CBR, consensus-based recommendation; EBR, evidence-based recommendation; PP, practice point

Dementia is diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria following comprehensive clinical assessment (PP; Figure 1), including consideration of delirium and depression, and a medication review to exclude medications with an adverse effect on cognitive function. Research suggests that GPs may not routinely conduct formal cognitive assessments when investigating symptoms.14 It is recommended that a validated instrument is used (refer to the Dementia outcomes measurement suite, available at www.dementia-assessment.com.au; PP). These include the 'GP assessment of cognition' (GPCOG; www.gpcog.com.au), a tool specifically designed for use in primary care settings. At the first assessment, a battery of screening blood tests should be performed (PP; Figure 1).

Structural imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should usually be used to exclude other reversible causes (PP), but this may not be necessary in people with moderate to severe dementia, or when otherwise inappropriate. The use of 18F‑fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and other newer diagnostic technologies, including fluid biomarkers, in routine clinical practice is considered premature (PP).

Research has shown that attending a memory assessment service is associated with improved carer psychosocial status;15 in a study in The Netherlands, there were no significant differences in the costs of care between attending a memory clinic and usual care.16 The guidelines recommend that people with a possible diagnosis of dementia should be offered referral to memory assessment specialists or services. GPs should expect that the memory assessment specialist or services should organise referrals for required health and aged care services (PP).

The committee engaged in detailed discussions regarding the manner in which medical practitioners should communicate the diagnosis of dementia. Key principles (as outlined in the recommendations) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Recommendations addressing communicating the diagnosis of dementia

|

Recommendation type

|

Guidance

|

|---|

|

PP

|

Follow the ‘Talk to me’ good communication guide and Alzheimer’s Australia Dementia language guidelines when communicating with people with dementia (www.fightdementia.org.au)

|

|

PP

|

Use an individual, gradual, respectful and honest approach when communicating the diagnosis

|

|

PP

|

People have the right to know or not know their diagnosis. If the person with dementia indicates that they do not wish to know their diagnosis, although this is rare, this desire should be respected. Ensure that the carer(s) and family receive adequate support and manage the consequences of this (eg driving). Resolve conflicts, such as when the carer(s) and family request the diagnosis not be communicated to the person with dementia, by further discussions over time. Provide information about dementia clearly, and emphasise that progression is often slow, treatments for symptoms are available and research into a cure is continuing

|

|

PP

|

After diagnosis, those with a history of depression and/or self-harm may be at particular risk in the first few months. While instances of self-harm or suicide are believed to be uncommon, support through counselling should be offered

|

|

CBR

|

After diagnosis, provide the person with dementia, their carer(s) and family with accessible information in verbal and written forms about dementia signs and symptoms, course and prognosis, treatments, medico-legal issues, including driving and sources of advice on financial, and legal and advocacy matters

|

|

PP

|

Provide information in a verbal and written form on community services, and record the advice and information given. Include information on services available through Alzheimer’s Australia, Carers Australia, Aged Care Assessment Teams and MyAged Care

|

|

CBR, consensus based recommendation; PP, practice point

|

Support for carers

Carers also need to have their health regularly reviewed and need to be made aware of respite services. There is a large body of research showing that providing comprehensive training for those who provide informal, unpaid support and care for a person with dementia (carers) can delay functional decline, reduce symptoms such as agitation and improve quality of life in the person with dementia and their carer(s).17–20 Alzheimer’s Australia and Carers Australia are good sources of information and support programs.

Living well and promoting independence

There is an increasing focus on promoting good health and independence in people with dementia. Consumers have been advocating for rehabilitation for people with dementia, and the government’s home care packages are now underpinned by the principles of restorative care and re-enablement.21 There is evidence that occupational therapy programs22 and regular exercise can delay functional decline (EBRs, low; Table 1).23 GPs should support patients with dementia to maintain a healthy, balanced diet (PP). An appointment with a dentist is recommended after diagnosis to determine a long-term treatment plan (PP).

Management of cognitive symptoms: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine

Many people with Alzheimer’s disease in Australia receive prescriptions for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme [PBS]).24 There is evidence that these agents can improve cognitive function and independence in activities of daily living in those with mild to moderately severe dementia (EBR, low).25 For a PBS-subsidised prescription, the condition must be confirmed by a specialist.

Recent evidence has also shown benefits of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in people who have dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease dementia,26 vascular dementia27–30 and severe Alzheimer’s disease (EBRs, low). In addition, the combination of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor plus memantine has been shown to improve cognition and reduce symptoms such as distress and agitation (EBR, low).31 However, these indications and combination therapy are not currently listed on the PBS. Medication review should be conducted within approximately one month of commencing therapy, assessing possible adverse effects and evaluating the appropriate dose, and within six months to consider if there is a demonstrated improvement in quality of life, behaviour and cognitive symptoms for prescription to be continued under the PBS.

The Guidelines recommend regular medication review that includes considering discontinuation (PP). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are not recommended for mild cognitive impairment (EBR, low).32

Management of other symptoms

Symptoms such as agitation, distress, apathy and depression are common in people with dementia. These symptoms are frequently expressions of unmet needs (eg lack of interesting activities or privacy, pain, need to eliminate, hunger or communication problems), and the first step is to identify and address these needs (PP). People with symptoms should be offered comprehensive assessment using an ABC approach (antecedents, behaviour description and consequence; PP). Symptoms should be measured using objective, validated tools so that the behaviours and effectiveness of any treatments can be monitored (PP). Non-pharmacological approaches, such as engaging the person with dementia in activities that are interesting and meaningful, should be implemented first (PP).

If someone is suspected to be in pain, a trial of analgesic medication should be undertaken with a stepped approach33 (EBR, low; Table 1). Medication, particularly opioids, should be used to complement, not replace, other options and only be used for a specified period (PP). Only if patients with dementia have severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (eg psychosis and/or agitation/aggression) should treatment with an antipsychotic medication be considered, given the increased risk of death and cerebrovascular adverse events associated with such medications (EBR, moderate). People who have dementia with Lewy bodies should not be prescribed antipsychotics as there is a high risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects (PP). For detailed recommendations on antipsychotics and other pharmacological treatments, refer to the full version of the Guidelines.6 Key evidence-based recommendations are provided in Table 1.

Ethical and legal issues

It is important to always seek valid, informed consent from patients when they have capacity, otherwise, the relevant laws for the jurisdiction should be followed (PP). It is also important to discuss the use of an enduring guardianship, enduring power of attorney and advance care plans with patients with dementia, their carer(s) and family while they have capacity (PP).

Palliative approach

A number of practice points addressing the palliative approach are provided in the full version of the Guidelines. The key points are that a palliative care service should be involved, when necessary, and that food and drink should continue to be offered. Consider referral to a speech pathologist for assessment of swallowing and feeding. For people with severe dementia, artificial feeding should not usually be used and any decisions regarding rehydration should involve the carer(s) and family.

Conclusions

New Guidelines for dementia provide practical recommendations for dementia care in Australia. The Guidelines emphasise timely diagnosis, living well with dementia, non-pharmacological management of behavioural and psychological symptoms, and supporting carers. GPs should refer to the full Guidelines for more detail. Work is underway to produce a consensus guide that addresses complex issues faced by GPs in more detail. This is expected to be released in 2017.

Declaration

This article is prepared for the purposes of dissemination of the Guidelines, and although it is targeted to a different audience, by necessity, it includes some duplication of material included in other dissemination articles published in the Medical Journal of Australia,7 Australasian Journal of Ageing34 and Australian Occupational Therapy Journal.35

Authors

Suzanne M Dyer PhD, GradCertPH, BSc (Hons), Senior Researcher, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

Kate Laver PhD, MClinRehab, BAppSc (OT); NHMRC–ARC Dementia Research Development Fellow, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA. Kate.Laver@flinders.edu.au

Constance D Pond MBBS, FRACGP, PhD; Professor, Discipline of General Practice University of Newcastle, NSW

Robert G Cumming MBBS, MPH, PhD, Professor of Epidemiology, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Craig Whitehead FAFRM, FRACP, Regional Clinical Director of Rehabilitation and Aged Care, Southern Adelaide Health Service, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

Maria Crotty MPH, PhD, FAFRM, Professor of Rehabilitation Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

on behalf of the Guideline Adaptation Committee, Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia in Australia.

Competing interests: A procedure was in place for managing conflicts of interest during development of the Guidelines, details can be viewed in the full Guideline document.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The guideline recommendations discussed in this article were formulated by the voting members of the Guideline Adaptation Committee comprising Robert G Cumming (Chair), Meera R Agar, Kaarin J Anstey, Elizabeth Beattie, Henry Brodaty, Tony Broe, Lindy Clemson, Maria Crotty, Margaret Dietz, Brian M Draper, Leon Flicker, Margeret Friel, Louise Mary Heuzenroeder, Susan Koch, Susan Kurrle, Rhonda Nay, C Dimity Pond, Jane Thompson, Yvonne Santalucia, Craig Whitehead and Mark W Yates. This work was supported by the NHMRC Partnership Centre on Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People (grant no. GNT9100000).