Case

A Caucasian man, 64 years of age, who is an ex-smoker (50 cigarettes/day, stopped 14 years ago) and social drinker, saw his general practitioner (GP) over a three-month period with persistent symptoms of odynophagia and sore throat. No other symptoms were reported and a repeated diagnosis of bacterial tonsillitis was made. Despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics, his symptoms failed to improve. His past medical history included osteoarthritis and gout.

While on holiday, the patient experienced increasing difficulties with eating solids because of food ‘sticking,’ as well as difficulty swallowing liquids. This prompted assessment by a duty doctor. On examination, the tonsils were enlarged and asymmetrical. Along with the above symptoms, this prompted immediate repatriation.

Question 1

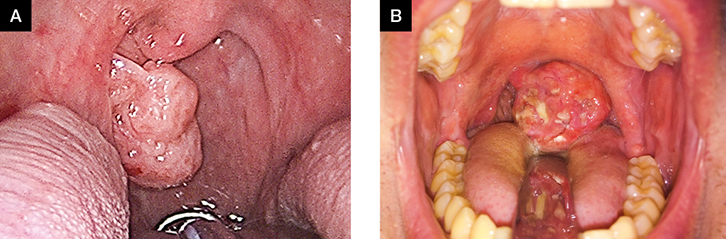

How can true tonsillar asymmetry, as seen in Figure 1, be differentiated from a peritonsillar abscess?

|

Figure 1. Clinical photographs of the oral cavity and oropharynx showing examples of tonsillar asymmetry

A. Intraoperative photograph of right tonsillar asymmetry due to squamous cell carcinoma (in a different patient to the one presented in the text);

B. Clinical photograph of a left tonsillar lymphoma |

Question 2

How should a patient with these findings be investigated and referred?

Question 3

What lifestyle factors are associated with an increased risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma?

Question 4

How is this patient likely to be managed in secondary care?

Answer 1

|

Figure 2. Clinical photograph of the oral cavity and oropharynx

This shows an example of left peritonsillar abscess. The asymmetry can be seen to arise from within the anterior tonsillar pillar rather than from the tonsil itself. |

The key feature of a true tonsillar asymmetry on examination is the position of swelling. In cases of peritonsillar abscess (ie quinsy), the swelling arises from the peritonsillar space. The tonsil itself is not asymmetrical but pushed into a medial position by the lateral oropharyngeal swelling. In both panels of Figure 1, the soft palate and tonsillar pillars are symmetrical but the tonsil on one side is clearly larger than the other. In Figure 2, the left tonsillar pillar is expanded by a peritonsillar abscess, the uvula is deviated to the right and the tonsil itself is not noticeably prominent.

Fortunately, malignancy rates in adults remain low in the context of asymmetrical tonsils that are not associated with risk factors, associated symptoms or mucosal abnormalities.1–7 Benign tonsillar asymmetry can be explained by hypertrophy, anatomical factors2,3 and extrinsic compression.8,9 There is a diverse range of causes for extrinsic compression, such as aneurysm, neoplasms of the deep lobe of the parotid and parapharyngeal neoplasms.8,9

Answer 2

Blood tests with particular attention to the full blood count can help to identify haematological malignancies. Depending on local protocols, throat swabs or serological tests can be sent with liver function tests to identify Epstein–Barr virus or group A streptococcal infection. Depending on the social and sexual history, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology may also be warranted.

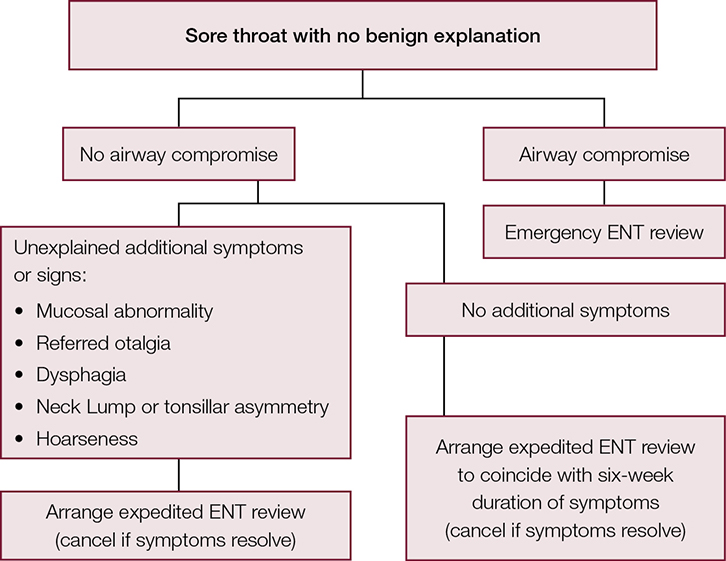

A diagnostic algorithm for patients with an unexplained symptom of sore throat can be seen in Figure 3. Sore throat with tonsillar asymmetry of the duration seen in this case should prompt expedited referral to ear, nose and throat (ENT) – head and neck services. Despite a low (approximately 2%) incidence of malignancy,5 the significance of missing tonsillar malignancy means that asymptomatic patients should still be referred on the basis of their signs.

|

| Figure 3. A diagnostic algorithm for patients with sore throat |

Persistent tonsillar asymmetry alone is an indication for referral and tonsillectomy (if there is progressive enlargement of the tonsil, associated neck lymphadenopathy or family history of malignancy).2 The presence of any mucosal abnormality, such as red, white or bleeding patches, is concerning and should also prompt expedited referral.4,10

Regardless of symmetry, progressive tonsillar hypertrophy in adults can be due to lymphoma. Therefore, direct questioning should screen for symptoms such as shortness of breath when lying flat, night sweats and lethargy. Depending on the results of the history and examination, which would also include abdominal examination for splenomegaly, head and neck or haematology referral can be made as appropriate.10

Answer 3

Smoking, alcohol consumption and betel quid chewing are all risk factors for tonsil carcinoma.11 Human papilloma virus (HPV) is also a risk factor, which should be sensitively explored by taking a sexual history, as HPV is associated with 40–90% of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas.12

Answer 4

Following clinical examination, fibre optic nasendoscopy would be performed to identify any nasal, postnasal space, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal abnormalities. This would allow airway assessment to determine the likelihood of airway compromise. In addition, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck and appropriate chest imaging would be arranged. If cancer is suspected, the patient is likely to be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting prior to tonsillectomy or biopsy to obtain a histological diagnosis.

Case continued

An MRI of the patient’s neck and CT of his chest showed a locally advanced right tonsillar tumour, which had metastasised regionally to the draining lymph nodes, but not to the chest. He was listed for urgent panendoscopy and incisional biopsy of the right tonsil. Histology revealed a small squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil with the presence of HPV, and he was referred for radical radiotherapy with curative intent following a multidisciplinary team meeting discussion.

Key points

- Smoking, alcohol and betel quid chewing are risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract.

- HPV is associated with 40–90% of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas.

- Duration of symptoms with no obvious benign cause for six weeks or longer should prompt expedited referral to ENT – head and neck services.

- If tonsillitis fails to respond to repeated courses of antibiotics, this should prompt specialist referral for the exclusion of a malignant cause.

- Tonsillar asymmetry can be differentiated from peritonsillar abscess by determining whether the swelling is intrinsic or extrinsic to the tonsil.

- The standard of care is still for persistently asymmetrical tonsils to be removed for histological examination.

Authors

Chrysostomos Tornari MB, PhD, MRCS, DOHNS, ENT Registrar, St George’s Hospital, London, UK. t.tornari@gmail.com

Krishan Ramdoo MBChB, MRCS (ENT), Research Registrar, Northwick Park Hospital, London, UK

Tse Choong Charn MBBS, MRCS (Edin), MMed (ORL), DOHNS, EBEORL, Associate Consultant in ENT, Sengkang Health, Singhealth, Singapore

Taran Tatla MBBS, BSc (Hons), DLO, FRCS(Eng), ENT – Head and Neck Consultant, Northwick Park Hospital, London, UK

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.