Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience greater morbidity and mortality, compared with non-Indigenous Australians.1 Chronic disease accounts for 80% of disease burden for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.2 In response to the National partnership agreement on Closing the Gap on Indigenous health outcomes,3 the $805 million ‘Indigenous chronic disease package’ (ICDP) was introduced in 2010.4 The ICDP included:4

- funding to employ Aboriginal health promotion officers and Aboriginal outreach workers to increase awareness in general practice

- funding to expand the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce

- reduced cost prescriptions (known as Closing the Gap [CtG] scripts) under the Indigenous Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) co-payment measure

- Practice Incentives Program Indigenous Health Incentive (PIPIHI), which allowed eligible general practices to receive additional payments for the chronic disease management of their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

One of the key performance indicators of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (and integral to the ICDP) is the uptake of the Health Assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People3 (Medicare Benefits Schedule item number 715 [MBS-715]), which encourages early detection and intervention of preventable chronic disease.5,6 On the basis of the 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census population data and Medicare billing data, there has been an increase in the uptake of MBS-715 nationally from 14.3% in 2011–12 to 21.3% in 2013–14.7

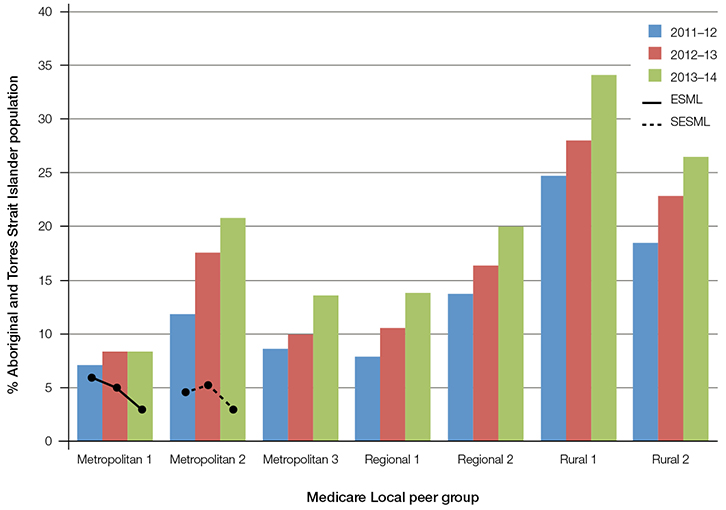

While there has been considerable improvement, rates of uptake are still below 22%, and there is variability across rurality,7 and both within and between primary healthcare services.8 Figure 1 shows the uptake of MBS-715 by Medicare Local peer groups from 2011–12 to 2013–14. Medicare Locals were a group of 61 regional organisations across Australia that coordinated healthcare services for a geographic area. They were organised into metro, regional and rural peer groups based on the socioeconomic indexes for areas and remoteness area categories.9 Medicare Locals have since been reorganised into Primary Health Networks. Although the uptake of MBS-715 has been increasing in many areas, rates in the Eastern Sydney and South Eastern Sydney Medicare Local areas have decreased (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. MBS item number 715 billed by Medicare Local peer group as percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population by financial year (2011–12 to 2013–14)

ESML, Eastern Sydney Medicare Local; SESML, South Eastern Sydney Medicare Local |

A number of barriers to MBS-715 uptake have been identified, including:

- access – affordability, appropriateness, acceptability and availability10–13

- lack of knowledge of its existence14

- lack of systematic Indigenous status identification systems.4–16

Much of this research either pre-dates the ICDP or was conducted in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific health services. A recent evaluation of the ICDP8 does not provide specific information on the barriers to MBS-715 uptake in metropolitan general practice, particularly in areas with decreasing uptake.

Considering the large investment made in the ICDP, and that approximately one-third of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples live in metropolitan areas17 and 50% access general practice18 from time to time, the aim of this study was to explore the current barriers to the uptake of MBS-715 in two metropolitan Medicare Local areas where the uptake had declined. This was done as part of a before-and-after study to improve Indigenous status identification rates and the acceptability and appropriateness of care provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in general practice.

Methods

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (UNSW HREC 11222) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee (AH&MRC HREC 796-11).

Recruitment and study population

The study was conducted in the South Eastern Sydney Medicare Local (SESML) and Eastern Sydney Medicare Local (ESML) areas. The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in each area based on the 2011 ABS census data was 0.8% (n = 3816) and 1.3% (n = 4541) respectively, although, these figures are generally accepted as being an under-estimation.19 There were 201 health services providing general practice services in SESML and no Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander–specific health services. ESML had 234 services providing general practice services and one Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander–specific health service, although it did not offer general practice services.

The Medicare Locals distributed an expression of interest form to general practices in their area. As this was a pilot study with limited funding, recruitment stopped once three eligible general practitioners (GPs) from separate practices in each Medicare Local area were recruited. One GP moved practices and wanted to remain in the study, so an additional practice was recruited in the ESML area. Given the nature of the intervention and limited funding, recruitment could not be extended to all GPs within a practice. Once a GP was recruited, permission to conduct the study was obtained from the practice principal. All administrative and nursing staff from the recruited practices were then invited to participate. In total, 31 out of a possible of 44 participants agreed to take part in the study (eight out of eight GPs, two of four nurses, one of one allied health professional, four of six practice managers, 16 of 25 receptionists). Recruited practices included two solo-GP and five multi-GP practices; of these, five were practitioner-owned and four corporation-owned practices (Table 1). Six practices were accredited against The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) Standards for general practices and four were enrolled in the PIPIHI (Table 1).

Table 1. Consultations, health assessments and number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients ≥18 years of age enrolled in PIPIHI and CtG Scripts 2010–12

|

| |

Practice code

| Total |

|---|

| 101* | 102*† | 103*† | 104*†‡ | 201†‡§ | 202*†‡ | 203†‡§ |

|---|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients identified

(% patient base) |

0

(0)

|

1

(0.02)

|

0

(0)

|

4

(0.1)

|

13

(1.1)

|

34

(0.2)

|

21

(1.3)

|

73 |

| Consultations past 2 years |

0 |

14 |

0 |

20 |

153 |

154 |

250 |

591 |

| MBS item number 715 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| MBS item numbers 703, 705, 707 and 10986|| |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| MBS item numbers 10987 and 81300# |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| PIPIHI |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| CtG scripts |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| PIPIHI and CtG scripts |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

6 |

0 |

5 |

11 |

CtG scripts, Closing the Gap (Indigenous Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) scripts; MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; PIPIHI, Practice Incentive Program

Indigenous Health Incentive

*Practice with more than two GPs

†Practice accredited against The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ Standards for general practices 4th edition

‡Enrolled in Practice Incentives Program Indigenous Health Incentives (limited to accredited practices)

§Solo-GP practice

||MBS item number 10986 is the healthy kids assessment. This item was searched in case any health assessments had been performed and miscoded in the medical record or individuals who just turned 18 or in case a health assessment had been performed in the two years prior to them turning 18

#MBS item numbers 10987 and 81300 are follow-up to MBS item number 715. These assessments were searched in case health assessments had been performed and miscoded in the medical record or in case a health assessment had been previously performed but not coded in the medical record |

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted following a series of standard questions and audio-recorded with the participants’ consent. Participants also completed a self-complete mail survey. The interview and survey questions (Boxes 1, 2) were based on broad themes identified in the literature as barriers to MBS-715 uptake10–15 discussed previously. The surveys and interviews were designed to cover similar topics for data triangulation purposes, and to obtain as many participant responses as possible (it was thought that some may have elected to complete only the survey or the interview, not both).

The first author attended each practice to identify what Indigenous status identification systems were in place. Then, the electronic medical records of patients aged 18 years and older were manually audited to determine:

- the number of patients with their Indigenous status recorded

- the number of consultations and health assessments that each patient who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander had in the previous two years

- whether these patients were enrolled in the PIPIHI and CtG scripts.

Administrative paperwork was also checked for enrolment in the PIPIHI and CtG scripts. Wherever possible, health assessments performed and billed were cross-referenced to see if additional health assessments could be identified. Baseline data collection occurred between May and September 2012.

Box 1. Interview schedule for general practice staff and GPs

|

- What do you think are the barriers to Indigenous identification in general practice?

- What do you think are the enablers to Indigenous identification in general practice?

- What do you think are the barriers to providing culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in general practice?

- What do you think are the enablers to providing culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in general practice?

- What are your views on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander–specific MBS item numbers available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients?

- What are you views on the new PBS co-payment measure available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients?

- (If the practice is accredited) What are your views on the practice guidelines and requirements for the PIP Indigenous Health Incentive and the Indigenous PBS co-payment measure?

- What are your attitudes, understanding and skills in the area of providing culturally appropriate service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

- What activities does the practice engage in to be more welcoming for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients?

- In your opinion, is the physical environment of the practice inviting to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community? Why/Why not?

- In what ways do you think this study could improve the acceptability of your practice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients?

- What other comments would you like to make?

|

| MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; PIP, Practice Incentive Program |

Box 2. Outline of the GP and practice staff self-complete questionnaire

|

- Demographics

- Indigenous status identification:

- How are patients identified?

- Who does the Indigenous-status identification in the practice?

- How effective is this method?

- Is Indigenous status recorded on the medical record?

- Engagement with AMS/ACCHS and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community

- Participant’s views on the barriers and enablers to the provision of culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, the CtG scripts and PIPIHI.

|

| ACCHS, aboriginal community controlled health service; AMS, Aboriginal Medical Service; CtG scripts, Closing the Gap (Indigenous Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) scripts; PIPIHI: Practice Incentive Program Indigenous Health Incentive |

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and thematic analysis was performed in Nvivo version 9.2. HS developed the initial code frame, and LJP and MH reviewed the coding of five interviews to identify differing or additional insights or meanings, which then informed the subsequent analysis. Data, source and researcher triangulation were used to increase rigour.20 Coded interviews were not taken back to the participants to verify the coding interpretation, as this may have influenced the intervention. Data saturation was reached within practices and professional groups.

Results

Response rates

Thirty out of 31 participants (97%) agreed to be interviewed and 29 (94%) surveys were returned.

Patient medical records software

Five practices used the Best Practice software, one used Medical Director and one used a custom-built package. All packages could record a patient’s Indigenous status according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW’s) National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets;21 however, there was no ‘refused’ option in Best Practice to enable staff to see if patients had already been asked their Indigenous status but had refused to disclose the information. The software capabilities varied; some did not have a prompt or reminder to perform MBS-715, and the MBS-715 templates in some versions did not pre-populate fields based on data available elsewhere in the patient medical record.16

Number of MBS-715 performed, enrolment in PIPIHI and CtG scripts

Table 1 shows that 73 patients were recorded as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent: five in SESML and 68 in ESML, which represents 0.1% and 1.6% of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander populations in those areas respectively. These patients had 591 consultations between them and three MBS-715s were performed; no other health assessments were performed. Eleven patients were enrolled in the PIPIHI and CtG scripts.

GP and staff knowledge and attitudes to, and beliefs about, Indigenous status identification systems, MBS item numbers and CtG scripts

A summary of coded response categories for themes arising from the interviews in relation to these three areas is provided in Table 2. More than half (17 out of 31) of the participants were not aware of MBS-715. Responses for those who were aware (mainly GPs) included:

- the MBS-715 allowed for earlier chronic disease detection and intervention

- it remunerated GPs for the additional time spent with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients

- the MBS-715 item number was not used

- the MBS item number system was complicated and laborious, and billing any health assessment was avoided as a result, or because of the work involved to try and recoup money if Medicare claims were rejected because patients has already had an MBS-715 billed elsewhere

- nursing staff at their practice were not actively involved in health assessments, which GPs considered too time-consuming to undertake without this support.

Two-thirds (65%) of participants were not aware of CtG scripts. Responses for those who were aware (mainly GPs) included that it helped reduce the financial barrier of medications and should be available for all eligible patients, not just those enrolled in the scheme.

Within each practice, there was no full consensus on what the Indigenous status identification processes were. Six participants did not know how Indigenous status was identified in their practice or that it was recorded on the medical record.

Table 2. GP and staff awareness of their Indigenous status identification systems, MBS item numbers and CtG scripts

|

| Node sub-code | GP

(n = 8) | Nurse

(n = 2) | PM

(n = 4) | Receptionist

(n = 15) |

|---|

| Indigenous status identification systems |

| Not aware how Indigenous status identified for new patients |

2 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

| Not aware how Indigenous status identified for existing patients |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| Indigenous status not asked for existing patients |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| Not aware Indigenous status recorded on the medical record |

2 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

| MBS item number 715 |

| Makes it more economical to see patient |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Good for early detection/prevention |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Too time consuming |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Lack of organisational teamwork |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Item number system too complicated |

3 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

| Do not use item numbers |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Not aware of item numbers |

3 |

1 |

0 |

13 |

| CtG scripts |

| Reduces financial barrier, increases medication compliance |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Should not be restricted to GPs enrolled in PIPIHI |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Unaware of CtG scripts |

3 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

| CtG scripts, Closing the Gap (Indigenous Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) scripts; GP, general practitioner; MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; MBS item number 715, Medicare Benefits Schedule item number 715 – Health Assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People; PIPIHI, Practice Incentive Program Indigenous Health Incentive; PM, practice manager |

Discussion

Research on the Medicare-rebated Health Assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in 2000–200422 and 2004–200814 found that the uptake was low. Despite the uptake having increased on a national level to 21.3%, it has decreased in some metropolitan areas.7 This study confirmed previously described barriers to MBS-715 uptake in general practice, including low rates of Indigenous status identification and a lack of awareness of MBS-715. Additional barriers found in this study were avoidance of billing health assessments (which has also been found in later research8), and the importance of having practice nurses actively involved in health assessments to support GPs.

A strength of this study was that it did not rely solely on MBS billing data, but manually interrogated patients’ records and cross-referenced with billing data wherever possible. In addition, a broad search for other health assessments and follow-up to MBS-715 (which would indicate that an MBS-715 had been performed previously) was undertaken; however, no additional health assessments were found. This suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients may not be receiving appropriately targeted care in some practices.

In their ICDP sentinel site evaluation, Bailie et al found that MBS-715 uptake was higher in sentinel sites than elsewhere.8 These results are expected considering sentinel sites included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander–specific health services, and one would assume there was a greater awareness of the ICDP performance indicators in the general practice sentinel sites than in general practice elsewhere in Australia.

Interestingly, ESML and SESML had CtG officers and Aboriginal outreach workers to help increase awareness in general practice and reduce patient access issues. Four of the seven participating practices were registered for the PIPIHI. Despite these practices presumably being primed to provide better chronic disease care for their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, there were still only three health assessments performed for 73 patients identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander out of 591 consultations. This suggests that although Indigenous status under-identification and lack of awareness of MBS-715 are barriers to MBS-715 uptake in general practice, avoidance of billing MBS-715 may be a greater issue because of the perceived complicated and/or laborious nature of the MBS item number system or because of fear of a claim being rejected.

Limitations

Participants self-elected to be involved in the study and may represent a group of motivated individuals; however, the characteristics of the GPs are broadly similar to those in Australia.23 The results were consistent with previous research regarding the barriers to Indigenous status identification15,16,24,25 and uptake of health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,14,22 indicating that the sample was not positively biased.

Participating GPs were from metropolitan Sydney and may not be representative of GPs in all urban areas. A low number of practices were involved and the results may not be transferable to other settings; however, the sample included a mix of solo-GP, multi-GP, practitioner-owned and corporation-owned practices.

Medical records extraction was confined to patients aged 18 years and older, and caution must be taken when comparing the figures to MBS-715 Medicare data, which has been provided for all age groups.

Implications for general practice

Although MBS-715 uptake has increased, it is still below 22%. Considering the investment made in the ICDP and the high Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in metropolitan areas, the low uptake in some areas is of particular concern. Further research is required to find suitable interventions to improve uptake in metropolitan general practice.

Many aspects of an MBS-715 may be covered over a number of consultations and are therefore not recorded and/or billed as such, and conclusions drawn based solely on these item numbers may not accurately represent the care provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. This raises questions about the usefulness of MBS-715 as a key performance indicator of chronic disease management.

Authors

Heike Schütze PhD, MPH, BSc (Biomedical), Lecturer, University of Wollongong, NSW. hschutze@uow.edu.au

Lisa Jackson Pulver PhD, MPH, GradDip (App Epi), Pro-Vice Chancellor Engagement & Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW.

Mark Harris MBBS, FRACGP, DRACOG, MD, Executive Director, Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, Level 3, AGSM Building, UNSW Australia, Sydney, NSW

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Funding support: Heike Schütze received an Indigenous Health Research Trainee Scholarship through the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and a PhD top-up scholarship through the Centre of Primary Health Care and Equity, UNSW Australia. Mark Harris received a NHMRC Senior Fellowship.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support and contributions of La Perouse/Botany Bay Aboriginal Corporation, Kurranulla Aboriginal Corporation, South Eastern Sydney Medicare Local, Eastern Sydney Medicare Local, and the participating physicians and practice staff. We also thank Helen Kehoe from AIHW for reviewing the manuscript.