Inequitable access to, and inappropriate, care are significant causes of the gap in health status between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians.1–3 Access4 is particularly relevant to urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples5 who are believed to be poorly identified by health services.6 The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) launched Closing the gap to ‘reduce Indigenous disadvantage with respect to life expectancy, child mortality, access to early childhood education, educational achievement and employment outcomes’.7 The success of Closing the gap requires culturally appropriate mainstream social, welfare, educational and health services,8 including general practice. Some success has been achieved in general practice through strategies such as Aboriginal liaison officers, practice visits, seminars and informal meetings.9 Barriers to success in meeting the cultural and clinical needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in general practice include difficulties with identifying these patients10 and a lack of appropriate cultural training.11,12

A non-judgemental and respectful approach, and knowledge of the historical, cultural, social, and medical and health system factors that have an impact on healthcare delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in general practice has been recommended.13 This is along with strategies for general practice staff to develop skills and confidence,9,11 and to access support and advice from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to facilitate culturally competent practice.13 These diverse findings suggest a need for practice-based interventions to translate cultural awareness and knowledge into culturally and clinically appropriate practice. However, there is currently little evidence on which to base such strategies. Building the evidence will require a strong and robust conceptual and theoretical framework.

Conceptual framework

The chronic care model (CCM) is an evidence-based, integrated framework that guides practices to redesign in order to manage chronic disease systematically and comprehensively.14 Working within this model, we drew on the following to guide the development of a whole-of-practice clinical redesign program to improve ways of thinking about, and ways of practising and ‘doing’, cultural respect:

- theoretical domains,15 cultural intelligence16 and mentorship17 frameworks

- existing Australian developments in cultural respect,8 safety11 and competence18

- review of successful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs19

- comprehensive consultations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, health professionals and policy makers.20,21

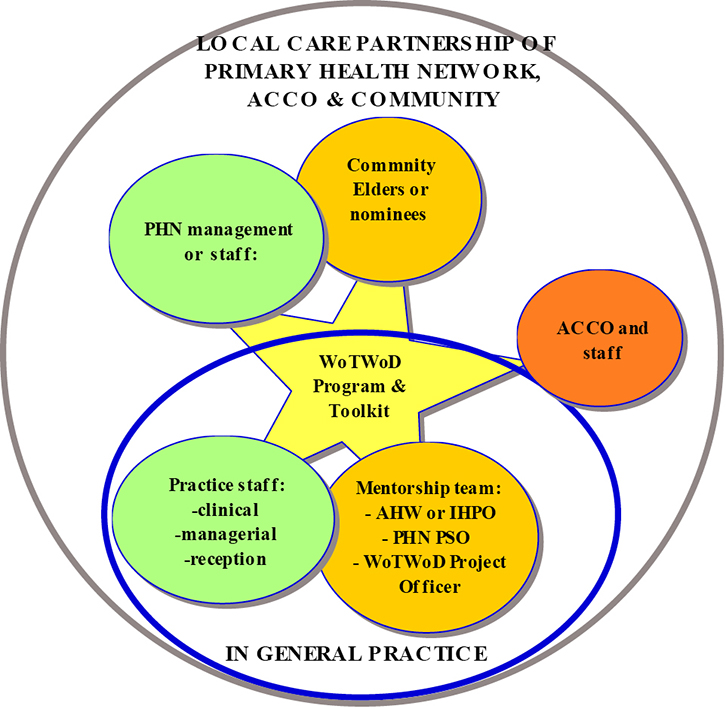

The ‘Ways of thinking and ways of doing’ (WoTWoD) cultural respect program is a flexible combination of personal, professional and organisational strategies that can be selected according to the readiness of the general practice to adopt them.22 Details of the WoTWoD program and toolkit are available online (www.cphce.unsw.edu.au/our-member-centres/academic-general-practice-unit). The WoTWoD toolkit was developed and refined after extensive consultations with communities in Melbourne and Sydney. The WoTWoD program to embed cultural respect activities into the practice begins with a cultural respect and orientation workshop. After this, an Aboriginal health worker (AHW) or Indigenous health project officer (IHPO) acting as a cultural mentor is teamed with the WoTWoD project officer to work with participating general practice staff, using the WoTWoD Toolkit as a guide. The WoTWoD program is overseen and supported by a local care partnership of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community elders and/or Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs) and the relevant Medicare Local (ML) or Primary Health Network (PHN). Figure 1 summarises how the WoTWoD program is implemented in the practice and community.

|

Figure 1. General practice and community actors in the WoTWoD program

ACCO, Aboriginal community-controlled organisation; AHW, Aboriginal health worker; IHPO, Indigenous health project officer; PHN, Primary Health Network; PSO, practice support officer; WoTWoD; Ways of Thinking and Ways of Doing |

Cultural mentorship is the critical element of the WoTWoD program. Mentors act with and through the WoTWoD cultural mentorship team and local care partnerships. Mentees include clinical, managerial and reception staff in general practice, and staff at the ML/PHN. Mentors and mentees work together using the WoTWoD Toolkit, in general practice and local care partnership, to achieve culturally and clinically appropriate care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples attending general practice and primary care. So what is mentorship?

Mentorship

Mentoring has historically been conceptualised in organisational literature as involving ‘an intense relationship whereby a senior or more experienced person (the mentor) provides two functions for a junior person (the mentee), one function being advice or modelling about career development behaviours and the second being personal support, especially psychosocial support’.23 Specific forms of mentoring, such as peer mentoring,24 may be formal or informal25 or diversified, involving individuals of different races, ethnicity or gender.26,27 In a review of the literature, Bozeman and Feeney17 proposed that mentoring be defined as:

a process for the informal transmission of knowledge, social capital, and psychosocial support perceived by the recipient as relevant to work, career, or professional development; mentoring entails informal communication, usually face-to-face and during a sustained period of time, between a person who is perceived to have greater relevant knowledge, wisdom, or experience and a person who is perceived to have less.

Cultural mentorship

The role of the cultural mentor is not new in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. It has been described as one in which the mentor has ‘an ongoing involvement with the research process and provides advice about world views and cultural values, beliefs and practices, and associated protocols which need to be followed’.28 Mentors may be from the research participant group, community or a professional/academic person with an understanding of the world views and cultural values, beliefs and practices of both researcher and researched groups. They may have contact with the participant group or community throughout the research process. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural mentorship has also been discussed in relation to general practitioner (GP) education, where it is characterised as ‘a relationship between an Aboriginal community member and a general practice registrar undertaking training at an Aboriginal health training facility’.13

Related to cultural mentorship is cultural brokerage. A ‘cultural broker’ is a person who facilitates the border crossing of a person or group of people from one culture to another – ‘the act of bridging, linking or mediating between groups or persons of differing cultural backgrounds for the purpose of reducing conflict or producing change’.29 Cultural brokerage may occur in an ad hoc manner based on needs, or it may be ongoing, especially if there is a need for negotiation or mediation. The roles of the cultural broker and mentor often overlap, and one person can carry out both roles.

This paper describes the conceptualisation and operationalisation of a cultural mentorship model, guided by the Bozeman and Feeney17 definition of mentoring within the WoTWoD comprehensive, multifaceted clinical redesign and service improvement program.

The study has been approved by The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (reference number 14-009), University of New South Wales (reference number HC14036), University of Melbourne (reference number 1441978), and Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council’s Ethics Committee (reference number 1005/14).

Methods

We used participatory action research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community Elders, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous staff of MLs and ACCOs to obtain relevant input into cultural mentorship models. Two workshops, one each in Sydney and Melbourne, were held to orientate participants to the WoTWoD program and achieve consensus on a useful cultural mentorship model.

Recruitment in two stages

Participating MLs in Sydney and Melbourne worked with the research team to recruit local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members or ACCOs to form a local care partnership. The care partnership nominated a number of their staff, including practice support officers (PSOs), IHPOs, AHWs and ALOs to participate in a cultural mentorship workshop. Participants in Melbourne included three Aboriginal Elders and one ALO, four IHPO, two coordinated care and supplementary services (CCSS) coordinators, and three managers from participating MLs. Participants in Sydney included two Aboriginal Elders and 14 ML staff (four Aboriginal and 10 non-Aboriginal).

Workshops

Workshop participants:

- completed a cultural quotient (CQ) self-assessment and discussed the findings as a group

- were given information about the WoTWoD program and resources

- discussed some of the cultural respect and disrespect scenarios in the Toolkit

- shared experiences with cultural mentors from the WoTWoD pilot studies

- discussed in depth about their perceptions of mentorship and menteeship, the benefits and/or harms, and requirements for success in the context of a clinical redesign program to embed cultural respect in general practice.

The researchers (STL, PL, JF, VW and IH) facilitated and participated in the workshops.

Results

The discussions of the participants on cultural mentorship were categorised into mentor, mentee, relationship and system dimensions. These discussions and summarised in Boxes 1 and 2.

A key principle emphasised was that for mentorship to be effective, mentors and mentees should be comfortable with their own identity (eg Aboriginality and/or ethnicity). Mutual trust is implicit in the mentor–mentee relationship where the participants must be prepared, flexible and mutually respectful if they are to achieve mutual understanding and the goals of clinically and culturally appropriate general practice and primary care services. Box 1 describes the range of perceived roles and responsibilities of the participants in a cultural mentorship relationship.

Potential benefits from successful cultural mentorship were perceived for all participants personally and professionally, with positive outcomes for their organisations, patients, communities and the health system. These include enhanced equitable access to, and use of, safe and high-quality care for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in general practice. However, potential harms from cultural mentorship were also perceived for all participants personally, professionally and organisationally (Box 2).

Examples of potential harms provided by workshop participants included inadvertent acts or statements that could be misinterpreted as cultural disrespect and managed inappropriately by mentor and/or mentee.

Box 1. Perceived roles and responsibilities of cultural mentorship

|

Mentors (mentorship team and local care partnership):

- Provide input about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perceptions of health and care

- Interact with staff to improve understanding of cultural respect in practice

- Be comfortable with own Aboriginality and/or ethnicity

Mentees (GPs, practice staff and ML staff):

- Improve cultural awareness among GPs and staff in the practice

- Seek feedback to tailor health services to meet community needs

- Implement quality improvement programs with a focus on improving cultural respect in the practice

- Develop connections with the community and community-controlled groups

- Be comfortable with own ethnicity and/or Aboriginality

Mentors and mentees work together to:

- be prepared, flexible and mutually respectful in the mentor–mentee relationship

- improve mutual understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and general practice or primary care services

- promote a holistic approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health among GPs and staff in practice

- activate and empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients

- advocate cultural respect among other patients in the practice

- advocate cultural respect with other services

- value the continuity of the relationships.

|

Box 2. Perceived potential benefits and harms of cultural mentorship

|

Potential benefits

Mentors (cultural respect team and local care partnership):

- Improved knowledge and competencies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals

- Improved understanding of general practice and primary care

- Improved guidance to community members attending general practice

- Improved mutual respect, cultural and professional

- Improved understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and mainstream healthcare relationships

Mentees (GPs, practice staff and ML staff):

- Improved cultural awareness among GPs and staff in the practice

- Improved holistic approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health by GPs and practice staff

- Improved tailoring of health services to meet community needs

- Improved standards of patient care by GPs and practice staff

Mentors and mentees:

- Improved mutual respect between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous health practitioners

- Improved professional linkages between community and general practice, including the endorsement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander–friendly practices and improved care pathways

- Improved Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community understanding of general practice

- Improved cultural safety that will encourage community to self-identify and improve potential for long-term GP–patient relationship

- Improved access to Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) supported Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health activities and subsidies that can increase practice revenue

Health system outcomes:

- Increased preventive health assessments and health maintenance activities, which could lead to fewer emergency department attendances and hospital admissions

- Cost/time savings, especially if appropriate services are available locally

- Improved community confidence, with empowerment and improved knowledge

- Improved awareness and use of, and access to, health services

Potential harms

- Mismatch of mentor–mentee personality types could lead to negative interpersonal experiences that could set back attitudes of mentors and mentees

- The business case for the WoTWoD program is not robust for general practice (ie the extent to which WoTWoD may improve outcomes or practice revenue is unclear)

- The business case for the WoTWoD program is not robust for Aboriginal community and ACCOs (ie the extent to which WoTWoD may improve access to care, processes of care or outcomes is unclear)

- If proved successful and not funded as part of mainstream service, this would be demoralising and potentially harmful to the community morale (victim of ‘pilotitis’)

|

Discussion

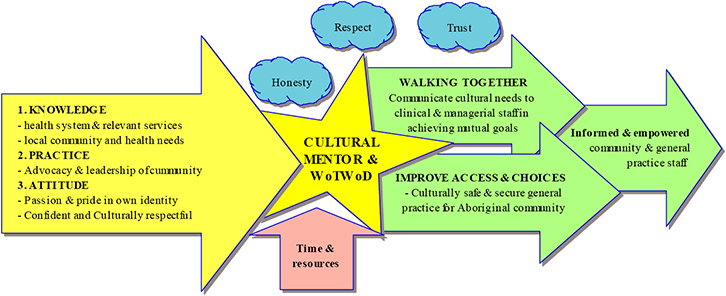

Taking the roles and responsibilities in the context of potential benefits and harms, there was consensus on the characteristics of cultural mentors most likely to generate benefit and minimise harm. These include:

- knowledge of the health system and services available to the local community

- leadership and advocacy for the community

- effective communication with general practice staff to impart cultural knowledge

- passion and pride in own identity, Aboriginality and ethnicity.

The cultural mentor, mentorship team and local care partnership need these characteristics to enable them to ‘walk together’ with practice and PHN staff to improve access and healthcare choices for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Figure 2). In addition to time and resources, there must be an environment where honesty, mutual respect and trust prevail. This guided the development of the operational model of cultural mentorship in general practice.

|

Figure 2. Desired attributes of mentors and mentorship environment

WoTWoD; Ways of Thinking and Ways of Doing |

A model of cultural mentorship in general practice and primary care

The workshop findings on the proposed roles and responsibilities, and potential benefits and harm of cultural mentorship, were analysed for conceptual consistency with the WoTWoD framework, which includes community, reception, consulting room and professional organisational dimensions. This led to the conceptualisation of a two-component model for cultural mentorship, one at the professional organisational level and the other at the practice level. These mutually inform and reinforce each other.

General and historical component to facilitate culturally respectful governance in the PHN

This is a local care partnership where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous consumers, managers and clinicians interact to ensure culturally respectful programs and services. It is an enhancement of the traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory/steering committee where respected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders provide mentorship to the organisation to improve organisational knowledge of the historical, cultural, social and health system factors that impact the planning, implementation and guidance of healthcare services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in general practice or community programs. Mentors may also be a liaison/conduit for local communities.

Practical component to embed cultural respect in the practice

This is the practice cultural mentorship team that includes a local AHW/IHPO, ML practice support officer and WoTWoD researcher. Using the WoTWoD Toolkit as a guide, the team would work with managerial and clinical staff to identify areas, processes and protocols in the practice where cultural respect may be improved by removing or modifying existing practices, or introducing new practices. Ideally, cultural mentors would need competencies to recognise the readiness of the practice to adopt and sustain a culturally respectful environment. Cultural mentorship in general practice is potentially another career pathway for the AHW/IHPO.

Conclusion

Using a participatory action research approach with the target community, we have systematically developed and are implementing a two-component model of cultural mentorship within the WoTWoD framework. It can potentially increase the likelihood of successful mentoring and minimise the likelihood of harm in the implementation. Most importantly, it requires mutual trust and respect to be successful. This cultural mentorship model will be examined, as part of the WoTWoD cluster randomised control trial, for its effect on cultural intelligence and practice.

Authors

Siaw-Teng Liaw PhD, FRACGP, FACHI, FACMI, Professor of General Practice, Faculty of Medicine,University of New South Wales, and Director, Academic General Practice Unit, South West Sydney Local Health District. siaw@unsw.edu.au

Vicki Wade, MSc (Nursing), Cultural Lead, Aboriginal, Health, National Heart Foundation, Sydney, NSW

Phyllis Lau, BPharmSci (Hons), GradDip Drug Eval, Pharm Sci, PhD, Research Fellow in Chronic Disease and Indigenous Health, General Practice, University of Melbourne, VIC

Iqbal Hasan, MBBS, MPH, Research Officer, Centre for Primary Health and Equity, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

John Furler PhD, FRACGP, Principal Research Fellow and Associate Professor, Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne, VIC.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the workshop participants, WoTWoD research team and Advisory Committee.