Case

Jake, 22 months old, presents to your practice for review. Twenty-four hours earlier, he was seen by a colleague and diagnosed with ‘viral-induced wheeze – ? asthma’. The general practitioner (GP) prescribed oral salbutamol, but Jake’s mother feels that this has made little difference. You wonder whether this is the best treatment.

The gathering global momentum of the US-based Choosing wisely campaign highlights the difficulties for individual doctors, when left to their own devices, to consistently ‘do the right thing’. Any chosen test or therapy should be truly necessary, evidence-based, safe and not duplicative of other interventions.1 We wish to highlight a case where a medication, although discouraged in recent national and international asthma guidelines,2 continues to be prescribed by some Australian medical practitioners.

The management principles of asthma are well established and the subject of numerous readily available clinical practice guidelines. First-line symptomatic treatment is short-acting, inhaled ß2-agonists (SABAs), such as salbutamol or terbutaline.2 In Australia, salbutamol is available in various forms, including pressurised, metered-dose inhalers, nebuliser solution, intravenous solution and a syrup for oral administration.3

Most current guidelines recommend the use of salbutamol by metered-dose inhaler via a spacer in the treatment of mild, moderate and severe acute asthma. Nebulised salbutamol is indicated in critical, life-threatening presentations.2

Outcomes for children with acute asthma in the community or hospital setting are no worse for salbutamol delivered via a spacer than nebulised salbutamol. In fact, outcomes for salbutamol delivered via a spacer are favourable in terms of limiting time in the emergency department and minimising side effects.4 Spacers are now widely used in the community. They are inexpensive, portable and easy to maintain.

There is minimal evidence to support the use of oral salbutamol for the management of asthma in developed countries. The practice is specifically – and increasingly strongly – discouraged in a number of guidelines (Box 1). Additionally, there is no evidence for any benefit in bronchiolitis5 or acute cough.6

Box 1. Specific reference to oral ß-agonist administration in recent asthma guidelines

|

|

Australia, 200613

|

‘Oral therapy with SABAs is discouraged in all age groups due to a slower onset of action and the higher incidence of behavioural side effects and sleep disturbance. It may have a limited role in the treatment of children under 2–3 years of age with mild occasional asthma.’

|

|

Australia, 20142

|

‘Oral short-acting ß2 agonists are associated with adverse effects and should not be used in any age group.’

|

|

New Zealand, 200514

|

‘Oral ß2-agonists for treatment of asthma symptoms should be discouraged in all age groups because the onset of action is slow (30–60 minutes), they are relatively ineffective, and the incidence of behavioural side-effects and sleep disturbance is relatively high.’

|

|

Malaysia, 201415

|

‘Routine oral bronchodilator use is discouraged due to its narrow therapeutic index and erratic gastrointestinal absorption resulting in variable and inconsistent efficacy.’

|

|

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), 201416

|

‘Oral bronchodilator therapy is not recommended due to its slower onset of action and higher rate of side-effects compared with inhaled SABA.’

|

|

Singapore, 200817

|

‘Inhaled bronchodilators are preferred as they have quicker onset of action and fewer side effects than oral or IV administration.’

‘Oral therapy is seldom required as most children are able to use inhaler therapy with the appropriate spacer device.’

|

|

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network,

201418

|

‘Oral ß2 agonists are not recommended for acute asthma in infants.’

|

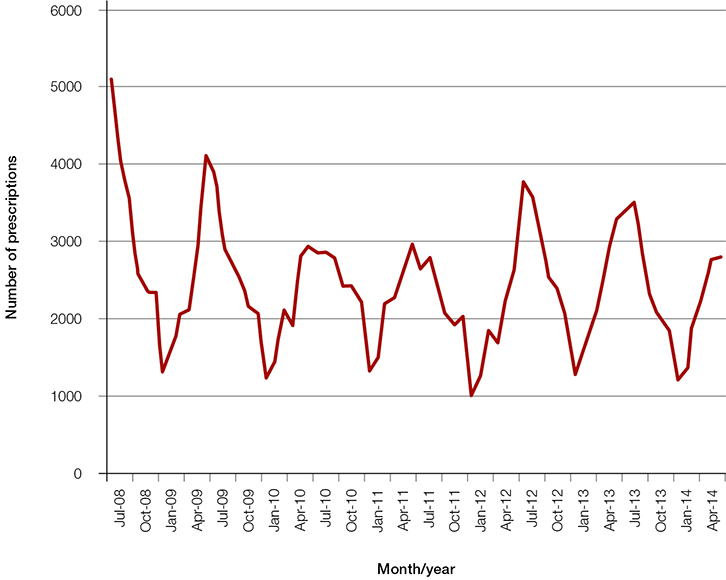

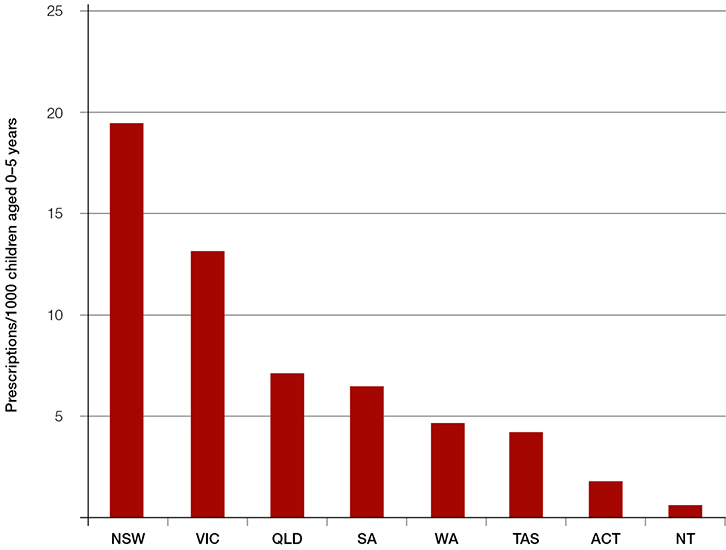

Despite this, an average of more than 28,000 prescriptions for oral salbutamol syrup have been dispensed each year between July 2008 and June 2014 (Figure 1).7 Prescribing peaks in the winter months, presumably in relation to childhood respiratory illness. Interestingly, prescribing patterns vary between states. The highest rates of prescribing oral salbutamol (per 1000 population of children aged 0–5 years) were seen in New South Wales and Victoria (Figure 2); more than half of all prescriptions were written in New South Wales.8

|

| Figure 1. Australian prescriptions for oral salbutamol syrup by month (July 2008 to June 2014)7 |

|

| Figure 2. Oral salbutamol syrup prescriptions per 1000 children aged 0–5 years by state (2013–14 financial year)8,19 |

Oral salbutamol preparations lead to a slower bronchodilator response than inhaled salbutamol.9 They also pose the risk of unintentional ingestion by young children. Although most ingestions are benign, potential complications include hypokalaemia, hypoglycaemia, restlessness and tachycardia.10

Despite recommendations against the use of oral bronchodilators in developed countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been reluctant to delete oral salbutamol from its list of essential medicines.11 Reasons for continued use – particularly in resource-poor settings – include:

- non-availability and relatively high cost of inhaled dosage forms

- ease of use of oral medication

- improved compliance9

- perceived social stigma of using inhalers

- lack of time and resources to enable patient education regarding inhaler technique.12

Ongoing prescription of oral salbutamol in some Australian settings may reflect socioeconomic pressures relating to patient education and stigma relating to inhalers, or practice patterns from doctors who have previously worked in developing countries. Other unidentified factors may also play a role.

Oral salbutamol continues to be prescribed in Australia despite clear evidence that it is less effective and more toxic than inhaled therapy. Current guidelines are unambiguous and do not support this overuse of an unnecessary treatment.2,13–18 More information may be required to identify reasons for persistent prescribing of oral salbutamol. One approach to reduce prescription could be targeted education to consumers, pharmacists and prescribers. Eliminating the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidy for oral salbutamol could also be considered.

Your response to Jake’s mum

You prescribe inhaled salbutamol with a spacer and mask, and instruct Jake’s mother about the appropriate technique. At your next practice meeting, you initiate a discussion on the topic of oral versus inhaled bronchodilators in children. The practice staff decide to conduct an audit of de-identified practice medical records and review recent practice guidelines.

Authors

Simon Craig MBBS, FACEM, MHPE, Emergency Physician, Emergency Department, Monash Medical Centre, Monash Health, Clayton, VIC; Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor, School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, Monash University, Clayton, VIC; Honorary Fellow, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, VIC. simon.craig@monashhealth.org

Martin Tuszynski MBBS, FRACP, Paediatrician, General Paediatrics and Emergency Department, Monash Children's Hospital, Clayton, VIC

David Armstrong MD, FRACP, Associate Professor, Head of Respiratory Medicine, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Monash Children's Hospital, and Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Monash University, Clayton, VIC

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.