Case

A man, 51 years of age, presented to his general practitioner (GP) with a three-to-four-week history of a rash on the palms of his hands, as well as a ‘lump’ on his penis that was pink and raised. The rash was not painful. He also felt weak, unwell and had lost weight. Past medical history included human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, hypertension and hypothyroidism. The patient had lived with HIV for several years but had refused treatment.

|

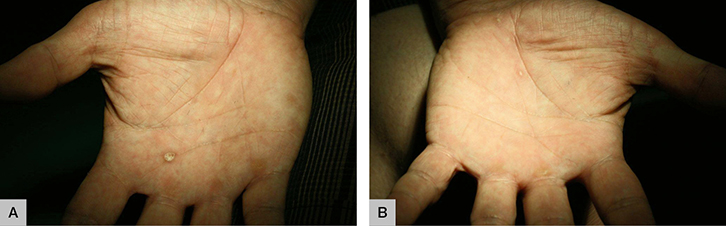

| Figure 1. Keratotic rash on the palms of the (a) right and (b) left hand |

On examination, a 2 cm posterior triangle cervical chain lymph node was palpable. A non-pruritic, macular, scaly keratotic rash was present on the palms of his right and left hands (Figure 1). Genital examination revealed a well-circumscribed singular, non-painful pink papule on the dorsal aspect of the glans penis corona, 0.8 cm in diameter (Figure 2). No inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. There was no discharge from the penis.

|

| Figure 2. Singular pink papule on the dorsal aspect |

Question 1

What are your differential diagnoses for this genital lump?

Question 2

What further history would you ask?

Question 3

What further examination would you perform?

Question 4

What investigations would you order?

Question 5

What is the final diagnosis?

Question 6

What is the management of this patient?

Answer 1

The differential diagnoses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses for a genital ‘lump’ that is not an anatomical variant in an adult who is HIV-positive10,11

|

|

Type of infection

|

Features

|

|---|

|

Bacterial

|

Secondary syphilis (Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum)

|

Condylomata lata of secondary syphilis are usually soft, flat-topped, skin-coloured papules

Primary syphilis – chancre – usually painless and indurated ulcer

|

|

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) L1–L3 serovars (Chlamydia trachomatis)

|

Papule, pustule or ulcer in the anogenital region (may be painful). Should be excluded in men who have sex with men (MSM) with positive chlamydia results

|

|

Viral

|

Human papillomavirus (HPV) serotypes 6 and 11

|

Genital warts – small, skin-coloured or dark papules, keratotic or flat-topped plaques

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV)

|

Single or multiple pearly papules with central umbilication

|

|

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

|

Erythematous papules that evolve into vesicles, then painful, shallow-based ulcers. Prodromal tingling or itch may occur

|

|

Herpes zoster (shingles)

|

Painful blisters – may evolve into pustules then crust (dermatomal distribution)

|

|

Parasites

|

Scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis)

|

Erythematous nodules and papules on genitalia – intensely itchy, worse at night and after hot baths

|

|

Iatrogenic

|

Fixed drug reaction

|

Large blisters – commonly evolve into shallow-based erosions

|

|

Fungal

|

Cutaneous (Histoplasma capsulatum)

|

Papules, pustules and nodules (very rare in Australia; however, infection may be acquired overseas)

|

|

Malignancy

|

Kaposi’s sarcoma (human herpesvirus 8)

|

In HIV infection – papules, nodules and plaques, accompanied by oedema of the shaft or scrotum

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

|

Small papules. HPV infection is a risk factor for invasive SCC

|

Answer 2

This patient’s risk for sexually transmissible infections (STIs) should be assessed. A sexual history should be obtained and information required should include:

- partners’ gender (men who have sex with men [MSM], men who have sex with women [MSW], or both)

- type of sex – oral, vaginal or anal sex (if anal – receptive, insertive or versatile)

- use of condoms

- regular or casual partners

- previous STIs.

Bloodborne disease risk profile (intravenous drug use, tattoos, blood transfusions) should also be assessed.1–4 Consider inquiring about neurological deficits – balance problems, hearing or visual changes, and cognitive impairment.3

This patient identified as a man who has sex with men and admitted to unprotected oral sex. He mentioned he had recently developed problems with his balance. Previous STIs other than HIV included genital herpes, syphilis and genital warts.

Answer 3

Further examination should include a full neurological assessment to rule out neurosyphilis – cranial, motor and sensory peripheral nerve examination.3 Examination of the ears, mouth and throat, as well as cardiovascular and gastrointestinal examinations, should be performed.1 Look for patchy alopecia as this may be the only presenting symptom of secondary syphilis.2

Answer 4

Consider the following tests for patients with HIV who present with a rash:1

- Chlamydia or gonorrhoea nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) from first pass urine, and/or urethral, rectal, cervical or self-collected vaginal swabs as appropriate. Add lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) if chlamydia NAAT is positive in rectal swabs of HIV-positive MSM.

- Throat swabs in MSM and sex workers.

- Syphilis serology including:

- Syphilis enzyme immunoassay (EIA) – a specific screening test. False positives occur in 1–2% of samples because of underlying inflammatory conditions (eg hepatitis), pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, ageing and malignancy.5,6 The sensitivity of EIA is 84% for detecting primary syphilis and 100% for syphilis in other stages; specificity is 96–100%.6,7

- Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) – a non-specific test. The sensitivity of RPR is 78–86% for primary syphilis, 100% for secondary syphilis and 95–98% for latent syphilis; specificity is 85–99%.5–7

- Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) assay – a specific test. The sensitivity of TPPA is 99% and specificity is 96%.5–7 False positives may occur in rheumatic heart disease.

- HIV plasma viral load, cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count and T-cell subsets, complete blood picture (CBP), serum biochemistry including liver function tests (LFTs).

Further information

The patient’s blood results returned showing the following:

- HIV viral load: 66,400 copies/mL

- CD4 (cluster of differentiation 4) count: 203 cells/mm

- syphilis screen: enzyme immunoassay (EIA) reactive; RPR titre: 1:256; TPPA reactive.

Answer 5

The diagnosis is secondary infectious syphilis in a patient with untreated HIV. The RPR was raised at 1:256, suggesting re-infection within the last four to 10 weeks; however, secondary syphilis may manifest up to two years after initial infection.5

Answer 6

Syphilis is a notifiable communicable disease. Partner notification is required for this patient (Figure 3). Treatment with intramuscular benzathine penicillin 1.8 g (2.4 million IU) is required for secondary syphilis as per World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.8 Urgent referral to an HIV medical practitioner (specialist GP, or infectious disease or sexual health physicians) for commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is necessary.

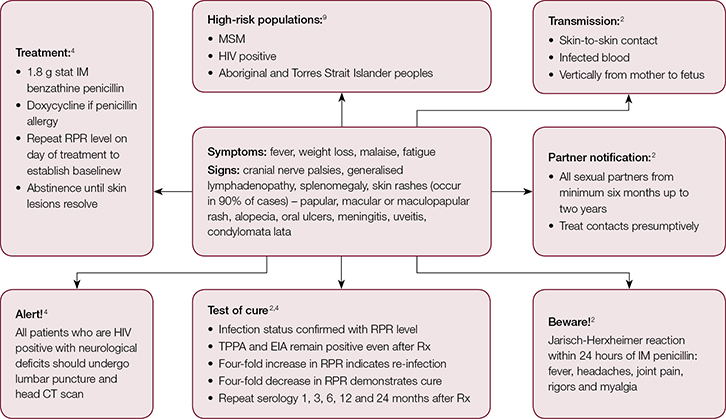

|

Figure 3. Management of secondary syphilis

CT, computed tomography; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IM, intramuscular; MSM, men who have sex with men; RPR, rapid plasma reagin |

The patient was extensively counselled on the benefits of commencing HAART to halt the progress of his HIV and reduce the risk of transmission to others. However, he refused treatment as it was against his personal beliefs. Lumbar puncture was performed given the patient’s neurological symptoms and returned negative for neurosyphilis. Further follow-up was arranged to repeat his syphilis serology, further discuss commencing HAART, and for opportunistic ophthalmology and audiology review in light of his chronic, untreated HIV. He failed to attend these appointments.

Syphilis has made a resurgence in Australian populations, occurring in

14 per 100,000 males.9

Key points

- Consider syphilis in a patient who is HIV positive and who presents with a rash.

- Syphilis enhances HIV transmission and may present atypically.4

- Syphilis serology should be checked every three months in patients who are MSM and HIV-positive.

- Syphilis can be transmitted by unprotected oral sex as well as insertive and receptive anal and vaginal sex.

Authors

Anna Dalton BMedSc, MBBS, Resident Medical Officer, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, SA. annahoustonk@gmail.com

Carole Khaw MBBS, DFFP (UK), FRACGP, PG Cert Pub Hth (Sex. Hth.), FAChSHM, Medicine Learning and Teaching Unit, Staff Specialist Sexual Health Physician, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.