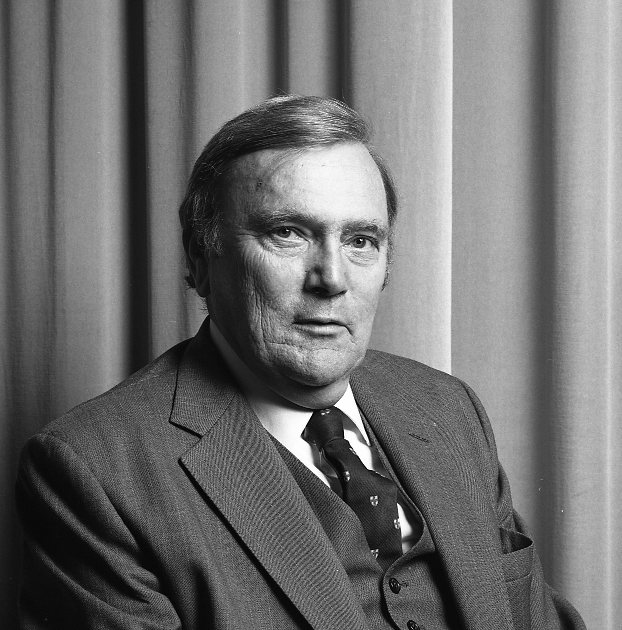

An RACGP past president

James ‘Jim’ Watson was an altruistic and complex individual who served as RACGP President, treasurer, WA Faculty President and Provost.1

He sat on the University of Western Australia (UWA) Senate for 20 years and was a long-term office holder in many charitable organisations.2,3 His most important legacy, however, was to have co-founded, with Archbishop George Appleton, St Bartholomew’s House, now a state-of-the-art community facility in Perth that advocates for the homeless and caters for several hundred people every night.4 James was also a noted collector of Japanese inrō and netsuke,5 and early Australian landscape art. After he retired from medical practice, he was on the cusp of becoming a successful vigneron.6

James’ father, Richard Grimes Watson, was an accountant who became a pig producer and the proprietor of the Kingston Farm Company, situated at Kingston and Beaudesert in southern Queensland. Between the two world wars, R Grimes Watson was the Chairman of the Pig Industry Council of Australia and a member of the Australian Meat Export Board. A staunch Presbyterian, he took a leading role in building a Presbyterian church to serve the Brisbane suburbs of Yeronga and Moorooka. He was also fond of wearing a kilt as his formal dress.7-9

James’ mother, the former Mary Lindsay Dowrie, was a music and English teacher at an Anglican girls’ school in Brisbane.10,11 Friendly with artists Lloyd Rees and the Lindsay family,12,13 Mary had what was described as a fabulous art collection and passed her love of English literature and art to her sons. In January 1976 she presented a gift of money to the RACGP to help finance several professors visiting from overseas. Selected by James himself, these visitors included Dr Donald Irvine, Honorary Treasurer of the RCGP, Professor Pat Byrne from Manchester, UK, Professor George Irwin from Belfast, Northern Ireland, and Dr Robert Braun from Brunn an der Wild, Austria.14

James had one brother, George, who was four years younger. He became a Cambridge don, a senior fellow at St John’s College and was the editor of the multi-volume New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature from 1969 to 1977. George unsuccessfully stood for a seat in the British Parliament in 1959 and was the senior treasurer of the Cambridge University Liberal Club from 1978 to 1992. His obituary described him as ‘a maverick English don’. One of George’s colleagues, John Kerrigan, a professor of English at Cambridge, added, ‘In person, as on the page, Watson liked to provoke, amuse and perform’.15 This could equally be a description of James at his best.

James Watson married Sheila Price on 1 June 1954. The daughter of English parents who held various postings in the British Colonial Service, Sheila was a handsome woman who taught physiotherapy at the Royal Perth Rehabilitation Hospital, Shenton Park Annexe, and treated children with poliomyelitis at Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH). She was a private, down-to-earth person with a quick wit who enjoyed a small circle of close friends.12 Sadly, Sheila developed a spinocerebellar ataxia while in her mid 30s. Nevertheless, she took joy in the pleasures of everyday life and ultimately outlived her husband by two years.

The couple’s first child, Mary Lois, was sadly stillborn.16 After this family tragedy, however, James and Sheila had three more daughters, Rosemary, Ann and Fiona, all of whom completed tertiary education.

Education

James attended the Brisbane Boys’ College, an independent day and boarding school affiliated to the Presbyterian Church. The school motto, ‘Sit Sine Labe Decus’, translates as ‘Let Honour Stainless Be’. The school has a proud tradition of academic pursuits, music and sport, but James does not feature in its Old Boys’ Association’s list of distinguished alumni.17 However, he was at least as distinguished as any who are listed under the category of medicine and health sciences, so it seems unlikely that he ever joined the school alumni association or informed them of his accomplishments. James was not interested in sports, but rather in books and paintings. One might imagine his school years were not happy ones.

His four medical lives

Paediatrics

James graduated from the University of Queensland in 1947. After one year at the Royal Brisbane Hospital he became a resident medical officer (RMO) at the Brisbane Children’s Hospital and, in 1950, at the PMH for Children in Perth. While at the Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH), James progressed to registrar and then to honorary assistant paediatrician and, in 1953, acting medical superintendent. In 1952 he worked in the UK where he obtained a Diploma in Child Health (DCH) (RCS Lond and RCP Eng). In 1954 James started a private paediatric practice in Mount Street, Perth, and shortly after moved to rooms at 246 St Georges Terrace. He was also an honorary assistant paediatrician to Fremantle Hospital, King Edward Memorial Hospital, the Sir James Mitchell Spastic Centre, the Lady Lawley Cottage by the Sea, a respite centre for children with physical or intellectual disabilities, and the Ngala Home for Parenting and Early Childhood services.18,19

Paediatrics in WA did not fully come into its own until the 1960s and 1970s. Prior to that, paediatric medicine was regarded as being the same as adult medicine, only practised on a small patient. Those who wished to treat children were predominantly GPs who went to the UK, obtained a position as a senior house physician in a children’s hospital and then passed the examination for a DCH from the Royal College of Physicians of London and the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

In the 1950s, the PMH was really a branch of the Royal Perth Hospital (RPH). Many of the honorary physicians and surgeons who taught adult medicine at RPH would also teach paediatrics at PMH.

Dr Bob Godfrey was appointed as the new medical superintendent and his aim was to staff PMH with fully fledged and dedicated paediatricians. In his view, a ‘fully-fledged’ paediatrician was a doctor who held Member Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) or Member Royal Australasian College of Physicians (MRACP) in adult medicine and had a DCH and several years’ experience of full-time work in a children’s hospital. Dr Godfrey’s plans fitted in well with the aims of the new medical school at UWA.

James lost his position as honorary assistant physician at PMH and slowly relinquished his other honorary paediatric positions.20 He closed his rooms in St Georges Terrace and continued to practise as a GP-paediatrician from the new practice he established in Manning.

The final blow to James’ quest for acknowledgement as a paediatrician was the advent of a Specialist Recognition Advisory Committee that did not grant him specialist recognition.21

James was bitter about not being classified as a specialist paediatrician. It took him some years to forgive the members of the Specialist Recognition Advisory Committee.

James had a way with children that resulted in a large following of adoring parents. Some of his patients, who are now very influential people, told me that he was a legend in their parents’ households.22

His daughter Ann recalled two events in the early ’70s that demonstrated the depth of James’ compassion. One was coming home distraught after diagnosing the inherited disease Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in the eldest of five brothers, all under the age of eight. The other was his reaction to the death of the three-year-old son of one of his patients, who had opened the rear door of the family car, fallen out and was run over. James soon after started to lobby for seat belts and child-proof locks on car doors.10

I first met James in early 1959. I was a fifth-year medical student doing an eight-week live-in residency at the PMH. James leapt out of an ambulance with a febrile child whom he had diagnosed with a possible case of meningitis. Although no longer on the consultant staff of the PMH, he acted as if he was. He stayed until the results of the lumbar puncture were reported as negative and then took a taxi back to his practice. Two days later the child was ready for discharge and his father sang James’ praises, saying his quick action had saved his son’s life. The paediatric registrar looked to the heavens. James clearly appreciated a bit of theatre in medical practice.

General practice

James built his general practice at the corner of Ley and Wooltana streets, just south of the Swan River in Manning. It was based on the health centre design advocated by the then medically influential Lord Stephen James Lake Taylor of Harlow.23 Clearly a persuasive man, James managed to convince the South Perth Council to make Wooltana Street a dead end, thereby providing plenty of parking spaces for his patients.

The 57 Ley Street practice opened on 23 March 1959 and attracted a mixed demographic of patients, including millionaires from riverside mansions to the west and housing estate patients to the east, as well as a large number of children whose parents stuck with him after the closure of his St Georges Terrace paediatric practice.

James also treated a lot of teenagers and their families. His underlying philosophy was to help them find their strength and develop a passion about something. He was particularly interested in counselling, family therapy, paediatrics, aged care, the disadvantaged and people who had problems with alcohol. His constant message to mothers was: ‘Mums have a special instinct. So if you think your kid is sick, you will usually be right’.10 It was good advice then and it remains so to this day.

James’ approach to helping troubled teenagers extended to his mentoring of young doctors from the Family Medicine Program (FMP). Dr Elisabeth Harris (now practising as Dr Elisabeth Wysocki) was an FMP registrar with James in 1978. She described him as a great mentor, stressing, by example, that the care of the patient was always foremost. ‘He always had time to sit down and talk. He gave you confidence that you could do the job and if you were not yet ready he showed you how to get the skills to be able to do it in the future,’ Harris said. She found him ‘bright, breezy, cheerful, full of energy, casual and charming’.24

James was a part-time senior lecturer in the new UWA Department of General Practice from 1977 – 1979. No student attached to his practice ever complained about being bored.

Dr Terry McCarter joined James at his practice in 1963, became a partner the following year and stayed until 1972. Terry said James taught him a lot about business procedures and setting up a medical practice. In fact, he felt that James’ true calling was big business. James was a shrewd investor who could see the potential development of an area. He also knew how to choose good staff, an opinion supported by James’ accountant and friend, Robin Halbert.26

James retired from practice in 1983, enrolled in a Master of Business Administration course (which he did not complete) and set up a practice management consultancy. His practice was purchased by Dr Jim Leavesley, a GP colleague, well-known author and ABC presenter of medical history. He delivered the eulogy at James’ funeral.3

Despite his concern for his patients, James was not a good public health example to them. He smoked Temple Bar cigarettes, sometimes while consulting, later changing to the rather pungent Camel cigarettes. Despite a heart attack and the pleas of his physician, James remained a secret smoker who used a menthol flavoured chewing gum to disguise the smell of tobacco. He was also a wine aficionado.27 A tall, large-framed man who was a bit overweight, James did little exercise. When he began his Ley Street practice he dressed in a tailored three-piece suit with a fob watch.12 In later years, he dressed more casually and sometimes eccentrically, such as wearing a cotton safari suit top with woollen trousers of a different colour.27 Either way, he did not look a good advertisement for the healthy living and preventive medicine that he regarded as a cornerstone of family medicine.28

Publications

In his paediatric days, James wrote two case reports on rubella and cat-scratch disease and was the third author of a substantial paper on staphylococcal pneumonia in infancy published in the British Medical Journal. If he did dabble with the idea of being involved with medical research in his early medical years, he did not proceed. In his GP days James wrote a few obituaries and letters on doctors’ fees, rehabilitation medicine and paediatrics in family practice.29 Nevertheless, he did value research and supported it in his committee days.

Medical politics, especially the RACGP

In 1962 James attended a Balint course at the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London, where he met Clifford Jungfer, a charismatic advocate for Australian general practice who convinced him to join what was then called the Australian College of General Practitioners.30

The RACGP set up its first official examination for membership in September 1968 and James was one of the original 300 who sat the examination. He passed and was immediately appointed as the WA representative on the Board of Examiners, a role he held until 1972.30

James attended his first meeting of the WA Faculty of the RACGP in the same month in 1968. At that meeting he proposed the formation of a Practice Management Committee, and was appointed its inaugural chair. He was made honorary secretary of the faculty a year later and was elected faculty chair in 1970. Stepping down after the customary two-year term, James took up the roles of honorary treasurer and vice chairman, and was provost and represented WA on the RACGP Council from 1970 to 1976. He attended meetings of the Faculty Board during his time as national President of the RACGP from 1976 from 1978. James decided not to stand for board membership in 1979 and took no further part in the affairs of the WA Faculty from then on.31

Six months after becoming RACGP President, James had a massive heart attack that left him with a large left ventricular aneurysm and heart failure.32 His only option was surgery, which then only had a 50% chance of success. However, he survived the surgery and resumed his presidential duties five months later.

In my view, the WA Faculty of the late ’70s was essentially a club. Members of its inner circle were true pioneers who had worked together since the faculty’s inception 20 years before. James was a different personality to any they had previously encountered on the faculty board. He was a flamboyant hustler skilled in committee procedure and, although he had attained high office, it seems James was never really liked nor trusted. As a medically qualified member of the UWA Senate and President-elect of the RACGP, he was a member of the eight-person panel appointed to select a foundation professor of general practice. Max Kamien, the author of this biography, was appointed. The WA Faculty was irate at this appointment and cast blame on, and questioned the probity of its incoming president.

‘We were disappointed that, of the two general practitioners on the committee, one, Dr M. Samuels (an established GP who was then President of the WA Branch of the AMA), had no point of contact at all with any educational or research body of General Practice, and the second, Dr J. Watson, was known for personal reasons to be a referee for one of the applicants. (I had asked him but since he knew he was going to be on the selection panel he declined).

We feel the real needs of General Practice and the community which it serves have been ignored in favour of academic and internal political motives.33

James stood his ground informing the WA Faculty Board that the decision of the selection panel was a unanimous one and had been supported by the four independent external assessors.

RACGP national

James took on the role of deputy chair of Council and honorary treasurer of the RACGP in 1969. In 1971 he was elected to Fellowship of the RACGP (FRACGP) and was the WA area co-ordinator of the FMP. He had wanted to be the inaugural director of the FMP in WA, but this position went to Dr Hugh Cook.34

James was the honorary treasurer of the RACGP from 1970–1976. At that time, the President-elect of the RACGP was elected by a ballot of members of Council. In April 1975, James and South Australia’s Dr Max Cooling nominated for President. The vote was a 5–5 tie, so the two candidates went to the office of Secretary General Dr Frank Farrar and tossed a coin.35 The following year, James was installed as President in the Mayne Hall at the University of Queensland, where he had attended his graduation ceremony 29 years before.32 Max Cooling became treasurer and then withdrew from RACGP affairs. Since that time, the President has been elected by universal suffrage.

James regarded his main achievements as President as forging working alliances with the other medical colleges and organisations, and bringing the governance and financial accountability of the FMP back to the RACGP Council.32 While the first situation had been initiated by Dr Robert Harbison, then Director of Training of the FMP, the second had, to some extent, been of James’ making. He had served as chair of the Board of Review, whose task was to liaise between the RACGP, FMP and the Government, so he would likely have known of all of the financial problems before he became RACGP President. This was a turbulent time for the FMP, which was beset by personality clashes, sackings, staff resignations and problems of financial accountability.35 It turned out that James’ success was only a temporary truce and the problems between the affluent and independent FMP and the cash-strapped and ineffectively large RACGP Council were to linger for many more years.36 James also recommended that Council form an executive to deal with managerial matters, allowing the Council to focus on policy.

The following is a list of the various medico-political offices James occupied through has career:1,2,18,19,31

- Australian Medical Association (AMA) – Board of WA Branch Council, 1969–79; Chair General Practice Section, 1976

- Joint Advisory Committee of the Royal Clinical Colleges in Australia – Chair 1978–79

- TVW Telethon Foundation – Director 1977–92

- Royal Society of Medicine – Corresponding Vice President, 1977–78

- Australian Association of Adolescent Health – President 1978–81

- King Faisal International Prize in Medicine – Australian Representative, 1981–92

- International Year of Disabled Persons – Deputy Chair, 1984

- Australian Association of Adolescent Health – Foundation member and later President, 1978

UWA connection

Convocation is the organisation that represents all graduates of UWA and is one of the four pillars of the university. Convocation elects six members of the UWA Senate, and this became his entry into the governance of the university. Elected to the Senate as a Representative of Convocation in 1971, James clearly did something right since he was re-elected to three further six-year terms, making him one of the longest-serving Senate members in UWA history. He was elected Warden of Convocation in 1984.2

James was particularly active on the Senate’s investment subcommittee and, being an avid collector of early Australian landscape art, he became chair of the University’s Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery Collection Board.2 In 1987 James made a financial donation to the gallery to help establish the James R H Watson Watercolour Acquisition Fund Collection.37

James enjoyed his membership of the University Senate, which he said added an extra breadth to his lifestyle.28 It certainly enabled him to ‘walk with politicians, visiting dignitaries, judges, academics, artists, leaders of business and a wide range of professional people. And as a GP he did, of course, preserve the common touch’.38 He had a network of acquaintances in many walks of life, and passed ‘the test of influence’ when all of the celebrities he knew ‘knew him back’.

Community work

1950s, Flight Lt. RAAF Reserve.

1960–64, Councillor, City of South Perth. James’ legacy was to start a therapeutic community group for people with mental health problems and leading the call for the since-established Manning Public Library.1,39

1980–84, Foundation President of the Watercolour Society of Western Australia.40

Toc H is an international Christian movement that began during the First World War in Belgium in 1915. Toc H members seek to ease the burdens of others through acts of service, as well as promoting reconciliation and work to bring disparate sections of society together. James was very involved in the organisation and served as President for 13 years.41

St Bartholomew’s House

If James had done nothing else in his entire life, his contribution to setting up St Bartholomew’s House for homeless men in Perth would have been a more than adequate legacy.

Given James was not usually one to hide his light under a bushel, I found it strange that I, along with many of the people I interviewed, were not aware of his involvement in establishing what is one of Perth’s most successful and enduring charities. Perhaps when one has overcome a very difficult challenge, the achievement speaks for itself.

James was never a shy man and would not hesitate to contact people he had never met if they could help with St Bartholomew’s. This is how he met the Right Reverend George Appleton, the 4th Anglican Archbishop of Perth. Appleton was enthroned at St George’s Cathedral on 12 August 1963 and it was only a few days later that James suggested the need to give Perth’s homeless men a place to go. Appleton had experience in such a venture from his time as vicar of St Botolph’s Church Aldgate in London. It was the archbishop who suggested James’ proposed home should be called St Bartholomew’s, after the London church and hospital that was founded by the monk Rahere in 1123 in order to care for the needy and homeless of the city.

By the end of 1963, St Bartholomew’s House had begun at the Rectory of St Bartholomew’s Church in Kensington Street, East Perth. Its facilities were relatively primitive, with mattresses placed on the floor of the Church Hall, but even then it played a vital role in giving assistance and shelter to Perth’s homeless men.4

St Bart’s, as it’s called, attracted some sponsorship from Perth’s Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Wardle, but most funds were obtained via fetes and yearly pledges of $25 solicited by James himself. Many of these donors were academic staff from UWA. The well-regarded West Australian portrait painter Owen Garde, who knew James, donated a portrait that was won at raffle by the architect Darryl Way and his wife, Margaret. She had worked in James’ Ley Street practice and she suggested that Garde paint a posthumous portrait of James, that they subsequently donated to St Bartholomew’s House. It now hangs in the recreation room of St Bart’s James Watson Hostel.26,28,42

James was St Bart’s chair of the board of directors from 1968 to 1972 and maintained his connection and interest in the shelter’s development for the rest of his days. After retirement from his practice in 1988 he took on the role of GP to St. Bart’s.43

In 1989 the board of St Bart’s began planning for a building that would provide permanent accommodation for men who were homeless, or at risk of becoming homeless. Building commenced in 1994 and took in its first residents in March 1995. James had died more than two years earlier, but he would have been humbled and proud that the new state-of-the-art building was named in his honour.

The residents of the James Watson Hostel produce a bi-monthly magazine titled What’s on Watson, which a charitable graphic designer, Herman Djohan, makes it into a professional-looking publication. The lead article in the illustrated 2013 Christmas edition featured one Dr James Watson.44

Art collection

James started collecting art while still a medical student.13 Of the 105 items in the collection, 39 were painted by famous Australian artists Lionel and Norman Lindsay.45 While his family auctioned off some of the art following his death, James had already gifted the bulk of it to help complete other collections.10

Vigneron

James long had an interest in horticulture and WA wildflowers. His home in the riverside Perth suburb of Applecross had a large garden, glass house and a potting shed. James would pot cuttings that were later sold at the fetes that supported his various charities.10

After he retired from medical practice, it was a natural next step for James to start growing grapes and making wine.

James was a long-time friend of Jack Mann, the iconic Houghton winemaker and doyen of the WA wine industry. When James decided to grow grapes he sought Mann’s advice and bought a 20 ha block of farming land south of Donnybrook, which he called New Lands. The company owned by JRH and SM Watson traded as Jimmy Watson Wine. The name was a spoof on the most prestigious and sought-after wine award in Australia, which was named after another Jimmy Watson who popularised wine drinking at his bar in Melbourne’s Lygon Street after the Second World War. By 1988, James had planted 11 ha of grapes and a commercial plantation of waratahs. His winemaker was Jack Mann’s son, Dorham.6

James’ first vintage included sauvignon blanc, chardonnay, cabernet franc and merlot. The official launch of the first New Lands Wine vintages was set for Saturday 5 September 1992. His friends received an official invitation with a few handwritten words: ‘My expert tasters say it is good wine. Hope you come and bring your mates. Anyone who is anyone will be there.’ He signed himself ‘Jimmy Watson’.28

Five hundred ‘anyones’ soon converged on James’ Donnybrook vineyard, where he was described as ‘proud and grand’3 and was reported to have said, ‘Should I die today, I will die a happy man’.21 Tragically, James died the next day, on Father’s Day, from a heart attack on his way back to his winery.16

Family life

James’ daughter Ann describes him as a larger-than-life man with a great laugh, whom she was, ‘lucky enough to have as my dad. Kind, sensitive, proud with humanist values that encompassed a sense of duty, well read, intelligent, tenacious, demanding, and who loved an argument or a debate.’10 Daughter, Fiona, puts it differently, ‘He could accommodate an audience, but he was not larger than life. Rather, he just wanted life to be larger.’12

James loved his wife Sheila and respected her opinions. At his most attentive, he would pour a brandy or a wine, talk about his and her day and take counsel from her. On other occasions James could be preoccupied with his political business. After his myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery and long rehabilitation, he became more empathic about his wife’s disabilities. Nevertheless, Sheila was particularly resentful about his frequent absences tending their vines at New Lands.10,12

On occasions, James seemed incredibly sad. I suspected much of this had to do with Sheila’s health. At a time when they should have been enjoying life they were unable to do so.

There was a certain side to James’ personality that was only seen by his friends. He seemed touched by and grateful for small acts of kindness, such as being visited in hospital or at his beach house.

James’ grandchildren lived outside of WA, but he managed to visit and was a good grandfather who would spend hours with them playing games, singing, cuddling and dancing. James is survived by five granddaughters.10

What made him tick?

I once playfully made the observation that James would have revelled in being a knighted medical academic and a university vice-chancellor. He did, it should be noted, not correct me. While a life with such titles was not going to happen, James managed to do the next best thing: he put his hand up, lobbied and became a member of numerous influential committees.

The most unusual was to be appointed an assessor for the King Faisal International Prize in Medicine.31 He told a reporter from the West Australian that it was ‘an honour for Australia to be represented on the selection committee’.46

It was impossible to have a neutral view about James Watson. But even his most trenchant detractors would agree that there was nothing mean about him. To his friends, he was a larger-than-life character who loved people. He was a compassionate man and was gratified to be able to help those who were down and out. James’ favourite saying was ‘There but for the grace of God go I’.10

He also liked to sponsor people whom he thought had something to offer. Geraldine Byrne had been a patient at his Manning practice for several months, but had never received a bill. When she asked about this discrepancy, James offered her a job as practice manager cum personal assistant.

When this worked out well, James encouraged Geraldine to finish her high school studies and get a university education, which he helped facilitate by allowing her to work within a flexi-time arrangement. He later bought her a car to reduce the travel time between her home in Cottesloe, his practice in Manning and Murdoch University. She had her eye on a pale blue car, but James insisted it be yellow or red since he considered those colours easier to see, and therefore safer.28

At Geraldine’s graduation, and at the publication of the first of her six books, James was ‘as proud as a peacock’,28 which, to many who knew him, was one of his endearing traits. He would puff out his chest and strut about the room as an expression of his happiness at the success of his protégée, or at ceremonial occasions and when accepting major donations from benefactors of his various interests. James enjoyed ceremony, with its academic gowns and floppy Henry VIII hats, and when he officiated, he did it with panache. He made new Fellows of the RACGP (and their families) feel they had really achieved something. His detractors found this body language immodest, but I disagree. I thought it added a necessary degree of gravitas and celebration to such occasions. James coveted the position of UWA chancellor (and also that of Murdoch University) and he would have excelled at the ceremonial tasks that went with that role.47

James came from an influential and wealthy upper middle class family with a ‘capitalist Protestant form of noblesse oblige of justification by good works’.12 His upbringing was influenced by Presbyterianism beliefs and his intellectual development was to remodel his previous influences and develop a more open mind about the affairs of the world.10

This resulted in him merging the conservatism of a previous era with the ideas of the new age. Women invariably liked him. Perhaps they sensed that he was both attracted to them as well as being a feminist with the firm belief that women could do anything, and educated women could do more.10

He sat on the WA State IVF Committee and worried about its effect on the adoption chances of children who needed a home. He was also ambivalent about euthanasia, believing society needed the aged, the weak and infirm in order to develop some soul and learn kindness and patience.10

Honours

In 1978 James was awarded the rank of Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) for services to medicine, education and the arts, an English award bestowed on those who render extraordinary or important non-military service in a foreign country. However, no mention was made of his passionate role in establishing St Bartholomew’s House.

He may not have been known as a person who could easily laugh at himself, but James would heartily approve of me quoting from an episode of the satirical British TV show, Yes Minister.

Jim Hacker MP is told an old joke by his Private Secretary Bernard Woolley about the meaning of the various senior public servants’ post-nominals.

Bernard Woolley: In the public service, CMG stands for ‘Call Me God’, and KCMG for ‘Kindly Call Me God.’

James was certainly more than happy to receive a CMG. If it had been in my power I would have pointed out his role in establishing St Bartholomew’s House and recommended him for a KCMG, a Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George. He would then have been addressed as Sir James, a title that would have befitted his stature and larger-than-life personality.

A reflection

James Watson was a complex person. Our paths crossed regularly between 1976 and 1983 and I always enjoyed, and was usually stimulated by, his company. He interacted with people from many walks of life and he was an intelligent, kind and generous man whose pithy insights and observations made us laugh. Above all, he tried to do good and he succeeded in leaving his WA world a much better place than when he first decided to try to change it.

He was survived by his wife Sheila, who died in 1995, and by his three daughters Rosemary, Ann and Fiona, and five granddaughters.

Max Kamien, Hon Archivist WA Faculty and Chair Archives Committee RACGP.

Acknowledgements

I thank all those past friends and acquaintances of James Watson who gladly gave me their time, recollections and written information on my subject. Special thanks go to James’ daughters Rosemary, Ann and Fiona, James’ practice manager, personal assistant and friend, Geraldine Byrne, and to Dr Eric Fisher, a past-President of the RACGP and long-time Chair of the RACGP Archives Committee who is the living memory of the RACGP. RACGP Archivist Tom Burgell and Knowledge Manager, Jane Ryan, provided their usual excellent services, as did UWA Archivist Maria Carvahlo. My friend Geoffrey Hall kindly edited the first draft and, as ever, has made this biography more readable than it would otherwise have been. My French wife, Jackie Kamien, used her superior knowledge of the structure of the English language to edit subsequent drafts.

- Farrar FM. Profile-James Richard Henry Watson-President Elect, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Australian Family Physician 1975; 4: 660.

- Maria Carvalho, University of Western Australia Archivist, email 5.12.2013.

- Leavesley JH. Obituary for James Henry Richard Watson 1923-1992. Australian Family Physician 1993: 22:14.

- Anon. Our Origin - St Bartholomew’s House. Available at stbarts.org.au/about-us/history-of-st-barts [Accessed 24 February 2014.]

- Traditional Japanese garments eg. robes called kosode and kimono, that had no pockets. Inrō are decorated containers for holding small objects such as medicines that were attached to netsuke (miniature sculptures) and then to obi (sashes) that held a kimono together. In 1982 Dr Watson donated his collection to the then Department for Japanese Studies that is now part of the School of Social Science at UWA.

- Zekulich M. Vintage Dr Watson uncorks new bottle. The West Australian 27.8.1992 p45.

- The Brisbane Courier 21.10.1929 p3.

- The Queenslander 19.3.1936 p38.

- The Adelaide Advertiser 15.1.1940 p19.

- Annie Angove, daughter. Letter 15.9.2013.

- Bronwyn Perry, Archivist, St Margaret’s Anglican Girls School, Ascot Qld 4007.

- Fiona Watson, daughter. email 18.12.2013.

- The James Watson Collection. Undercroft Gallery, UWA 4 Feb-3March, 1987.

- Thomas Burgell, RACGP Archivist. email 12.12.2013.

- Reisz M. George Watson, 1927-2013, Obituary, 5 September 2013. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/news/people/george-watson-1927-2013/2006968.article [Accessed 21 February 2014.]

- Rosemary Watson. Telephone interview 28 February 2014.

- Brisbane Boys’ College http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Brisbane_Boys’_College_Old Boys [Accessed 24 February 2014.]

- Who’s Who in Australia 1977, 1988, 1992.

- Medical Directories of Australia 1958, 1988.

- Emeritus Professor Ian Lewis – paediatrician Princess Margaret Hospital 1954-1970. Telephone interview 16 December 2013.

- Emeritus Chancellor Prof Alex Cohen. Interviewed 10 February 2014.

- John Cruthers, art consultant and private curator, son of Sir James and Lady Sheila Cruthers, WA philanthropists and art collectors. Telephone Interview 18 December 2013.

- Taylor S J L. Good general practice – a report of a survey by S.Taylor. Lond. : O.U.P., 1954.

- Dr Elisabeth Wysocki. Telephone Interview 22.11.2013.

- Dr Terence McCarter. Interviewed 22.11.2013.

- Mr Robin Halbert, Accountant, Board Member St Bartholomew’s House. Interviewed 9.9.13.

- Geraldine Byrne. Interviewed and examination of her James Watson memorabilia 28.8.2013 and 5.3.2014.

- Anon. Perth doctor is new RACGP President. AMA Gazette, October 1976.

- a) Watson JR. Hepatosplenomegaly as a complication of maternal rubella; a report of two cases. Med J Aust 1952; 1: 516 b) Wallman IS, Godfrey RC, Watson JR. Staphylococcal pneumonia in infancy. Br Med J 1955; 2: 1423-7 c) Watson JR. Med J Aust. Cat-scratch disease in Western Australia: a report of three cases. Med J Aust 1956; 43:20-1 d) Yuille D, Watson JR. Doctors’ fees and costs. Med J Aust 1971; 1:1245-6 e) Roberts RW, Watson JR. Alfred Nailer Jacobs. Med J Aust 1976; 1: 1018-9 f) Watson JR. Training in paediatrics for family practice. Med J Aust 1979; 2: 425 g) Bedbrook G, Watson JR. Rehabilitation Medicine. Med J Aust 1979; 2:545.

- GP News. Australian first for past-President. Australian Family Physician November 1983:827.

- WA Faculty Minutes 1956-1979.

- JRH Watson, 1976-1978 in The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 1958-1978. The RACGP: 36-7.

- Howard Watts, acting Chairman WA RACGP to Chancellor UWA. 25.8.1976. Leaked to West Australian Newspaper by Board member and published 6.10.1976.

- Dr Hugh Cook. Interviewed 9.12.2013.

- Dr Eric Fisher. Past President RACGP. Interviewed 17.10.2013, 28.2.2014, emails 28.2.2014; 1.3.2014.

- Wilde S. 25 Years under the microscope. History of the RACGP Training Program, RACGP, 1973-1998: 7, 31-35.

- Kate Hamersley, Registrar (UWA Collections), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, UWA email 19.11.2013.

- I have paraphrased the words of the last sentence in James Watson’s hand-written letter of appreciation for the organisational and secretarial work done by Geraldine Frances Byrne in organizing his office during ‘his 26 months Presidency of the largest Royal College in Australia’. 19. 10. 1978.

- Annie Angove (daughter) email 31.12.2013.

- Valerie Parker, founder of the West Australian Watercolour Society, 1980. Email 26.11.2013.

- Toc H is an international Christian movement that began during WW1 as a soldiers’ rest and recreation centre at Poperinghe, Belgium. The name is an abbreviation for Talbot House, ‘Toc’ signifying the letter T in the signals spelling alphabet. It aimed to promote Christianity and was named in memory of Gilbert Talbot, son of Edward Talbot, then Bishop of Winchester, who had been killed at Hooge in July 1915. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toc H [Accessed 24.2.2014.]

- Darryl Way. Interviewed 14.1.2014.

- Lynne Evans, CEO of St Barts 2000-2001.

- Kamien M. Dr James Watson. What’s on Watson, Christmas and New Year edition 2013, Issue No.5 December 2013, James Watson Hostel, Perth.

- The Estate of Dr James Watson CMG, Auction Catalogue, HE Wells & Sons, March 18, 1993.

- Anon. $65,400 prize for medicine. The West Australian 1981 April 5; p28.

- Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Bolton, Chancellor Murdoch University 2002-2006.Interviewed 5.3.2014.