A superb teacher of young doctors

Patrick (Pat) Edmond’s obituary in the New Zealand Herald, 22 October 2014, stated that ‘Pat was a WWII major, a surfer, a mountaineer, a skier, a champion sunbather and a popular doctor who never knew what generation he belonged to’.

He was a solid citizen who really cared about his fellow man.

Pat was born in Wandsworth, south-west London where his father, Frederick Edmonds, practised as a dentist.

His mother, Marcelle Plantade, was a flamboyant French woman from whom Pat learned the French language and developed a love of French culture.

He had an elder brother, Jack (dec) and a younger sister, Denise. He attended Surbiton School, an independent Anglican school in south-west London.

Army service

In 1941, Pat enlisted in the City of London Infantry Regiment – The Royal Fusiliers. He volunteered to be a glider pilot and in 1943 was transferred to the recently formed Glider Pilot Regiment with the rank of second lieutenant. This was one of the British Army’s elite red beret regiments. Its motto was ‘Nihil est impossibilis’.

His training, in the Army Air Corps, was rigorous and designed to make him into a total soldier, able to use all the weapons and equipment that gliders carried into battle. Flight training consisted of 12 weeks in Tiger Moths, a further 12 weeks in light Hotspur gliders, then six weeks in heavy gliders. These were Airspeed Horsa Gliders, designed to surprise by being able to deliver an airborne platoon of 28 men or two jeeps to a precise spot, day or night.1

Pat’s first and only mission was in Operation Varsity, the Allied crossing of the Rhine and invasion of north-west Germany on 24 March 1945. The aim was to winkle out the last segments of German defence and then strike for Berlin. Operation Varsity was the last major airborne offensive of WWII and remains the largest and most successful drop in history. It involved 2937 gliders – 2057 from the USA and 880 from Great Britain.

Pat was co-pilot of a Horsa Mk I (Chalk number 73) which departed from RAF Gosfield, towed by a C-47 Dakota. On board were members and equipment of the First Battalion of The Royal Ulster Rifles tasked to land on LZ ‘U’ as part of the plan to take and hold the level crossing and area around Hamminkeln railway station and to create a defensive perimeter linking all three of the Battalion’s objectives.2 Eleven per cent of the British glider pilots were killed, including Pat’s best friend and co-pilot George John D’Arcy-Clark.3

We called our gliders ‘flying coffins’. They were built mainly of plywood and had no protection from the accurate German guns. Sitting there with no parachutes, we felt like sitting ducks. One’s only hope lay in the skill of the glider pilot, who we prayed would get us down in one piece.4

Pat’s glider landed amongst German troops and he had to fight his way back to the main body of Allied troops. This entailed having to shoot a young German soldier, an event that haunted Pat for a long time.3 Pat hated the horrors of war and did not see warfare as a solution to international problems.5

He stayed in the Army Air Corps until 1950, leaving with the rank of Major. He was awarded the War Medal, the Defence Medal, the 1939–45 Star and the France and Germany Star.2

Medical life

After his army service Pat decided that he wanted to change tack and enter a helping profession. He obtained entrance to dentistry but soon transferred to medicine at The London Hospital Medical School in Whitechapel (now The Royal London Hospital). As a student Pat was liked and respected by his peers and was affectionately known by his many friends as ‘the major’ or less often by his initials ‘PAS’.5 His watering hole was the still standing, Good Samaritan pub. He also had many friends outside of medicine particularly in the worlds of art and the theatre.

Pat was deeply involved in hospital student events and activities and was prominent in the Art Club, where he would exhibit works of art and pottery at the annual show. He and I once conducted a very famous physician around that art exhibition. When shown one of Pat’s paintings the famous man said ‘Horrible!’ ‘I agree’ said Pat with a straight face. We all enjoyed this moment long after, especially since the painting was actually very good. Pat had a wonderful sense of humour and enjoyed laughing at himself especially when he made a mistake.5

Pat graduated as a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (LRCP) and Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) in 1956 and obtained house jobs at the London and Royal West Sussex hospitals, followed by a paediatric post at St David’s Hospital in Bangor, Wales and an obstetric position at Derby City hospital. He was an extremely able house officer.5

In 1959 he moved to New Zealand and worked as a locum in the lower Hutt and Wellington regions. Between 1961 and 1967 he moved between Wales, Wellington and Auckland. In the last three of those years he was a doctor in the New Zealand Navy.

In 1968 he worked his passage to the UK as a ship’s doctor. There he furthered his medical education and then returned to New Zealand in 1970. He then worked for a year as a locum before joining a group practice in Takapuna on the north shore of Auckland. In 1978 he set up his own practice at 22 Cecil Road in the pleasant Auckland suburb of Milford. His patients held his medical skills in high esteem and he was a very popular GP. He worked at Milford until 1985 when he sold his share of the practice to his partner, Dr Martin Robb.

In 1984 he attended a sexual health course in Perth. He then toured WA and was attracted to the Pilbara and Kimberley regions and the Aboriginal people who lived there. The following year he moved to WA and became a permanent locum for the Royal Flying Doctor Service and various Aboriginal community controlled health services, particularly in Derby, Kununurra, Exmouth, and Wyndham.

In 1992, he added to his career the role of part-time GP with the Curtin University Student Health Service. He continued to do remote locum work and teaching until he was 85 years of age.

Teacher

There were many general practice registrars working in north-western Australia. Pat was recruited by the RACGP Family Medicine Program (FMP) as an External Clinical Teacher (ECT). He left an unpublished manuscript describing his teaching philosophy and method:

I have visited many practices in WA from Wyndham to Albany, usually staying one or two days. It was my experience that if it were possible to dine with the registrar at a restaurant before we started serious work, we were able to learn a great deal about each other and this resulted in dispersing many of the understandable anxieties created by meeting me for the first time.

ECT visits have certainly been a pleasurable and learning experience for me. It would be unusual if I left after one of these visits without learning something useful from the registrar!

Learners love teachers like that. It was little wonder that general practice registrars held him in the highest regard.

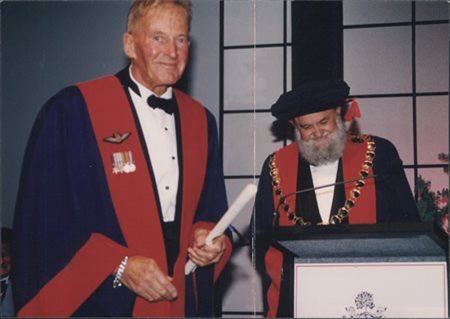

In 1996, the RACGP made it a requirement that ECT visitors had to be Fellows of the RACGP. Pat was 73 years old and was not going to sit the FRACGP exam. FMP was keen to keep him so they made the (successful) case that he was an exceptional doctor and deserved an honorary Fellowship. These are not given out lightly. They are awarded to distinguished presidents of other national general practice colleges, notable medical scientists and luminaries, such as the longest serving Prime Minister of Australia Mr Robert Menzies, and HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, then president of The Royal College of General Practitioners, after he gave the occasional oration at the Academic Session of the 1973 Annual General Meeting held at the Lakeside Hotel, Canberra.6

Family life

While working in Bangor (Wales), Pat met and courted Elizabeth Butler, who was a nurse. They married shortly after he migrated to New Zealand. They had two children, Mark, who lives in Perth, and Simon who lives in Wellington. The marriage ended in an amicable divorce in 1975. After this Pat had a number of steady girlfriends but he remained unmarried.

In 1969 he went to see the ‘hippie’ musical Hair. He had an epiphany and became an acolyte of the Age of Aquarius, espousing personal liberation, interpersonal trust, understanding and harmony. He put away his

suit and tie and started wearing jeans and open necked shirts.

Pat was very British in his speech, appearance and manner, but never had any airs or graces and was always down to earth. He was a good listener and a modest and congenial companion. He had the ability of being able to relate to anybody in any position, anywhere, in the hospital, his practice or in the street, and he treated every person with equal respect whoever they were. He was a person who would always come to the help of other people, including strangers.5

His eldest son, Mark, said that Pat would never tell a lie and that the only time he had ever seen him get angry was when someone questioned his integrity.

Members of the Glider Pilot Regiment had a reputation for tenacity. Pat maintained his tenacity and sense of duty even in his hippie period. A medical colleague, Dr Hamish McGlashan, relates an episode that occurred in the Kununurra District Hospital when Pat was 80 years old. The hospital was short staffed and Pat had been on active duty for 140 hours. Hamish told him to go to bed and he would run the outpatient clinic. Pat said he was rostered to do it. Hamish required the assistance of another doctor to get Pat to the on-duty doctor’s bedroom. There he immediately fell asleep and did not surface until the following day.7

Pat had a love of physical activity, especially running and skiing. He began each day with a run. This stopped in his late 80s when he became increasingly frail and took up residence in an independent living flat at St Louis Retirement Estate in the Perth suburb of Claremont.

He was still able to be the guest speaker at the RACGP WA Faculty end of year dinner in 2013. Professor Max Kamien asked him to speak about his experiences in the Glider Pilot Regiment. He did it well, with a mixture of pride for their achievements and sorrow for his many close companions whose lives had been lost. On the drive back to his flat he discussed the idea of donating his body to the anatomy department at UWA. He had heard that they had a shortage of bodies for dissection and reasoned that he could still be of use even after death. He did complete the necessary paper work that enabled him to fulfill his last altruistic deed.

Dr John Andrews, his friend from his medical school days, summed up his influence on his family, friends, acquaintances and students: ‘He was a splendid man and one we will all greatly miss’.5

Patrick Edmonds was a mensch – a real mensch.8

Professor Max Kamien

The author wishes to acknowledge Mark Edmonds for his assistance in providing photos and information about his father.

- These gliders were named after ancient warriors. Horsa and his brother Hengist were the two Germanic brothers who led the fifth century Anglo-Saxon invasion of southern Britain.

- Wright SL. The Last Drop: Operation Varsity 24–25 March, 1945. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008. Email 28 February 2015.

- Patrick Edmonds. Operation Varsity. The Eagle. December 2003: 20–21.

- Jim Corbett. Operation Varsity – The Rhine Jump – 24 March 1945. Available at www.britisharmedforces.org/pages/nat_jim_corbett2.htm [Accessed 29 May 2015].

- John Andrews MBBS, MD, FRACP, FRACR. Student contemporary at the London Hospital Medical School and lifelong friend. Email 3 April 2015.

- Barry Fatovich MBBS, FRACGP. Then Director of the West Australian branch of the Family Medicine Program. Email 23 February 2015.

- Hamish McGlashan MBChB, FRCOG. Personal communication 31 March 2015.

- ‘Mensch’ is a Yiddish word that has become part of the North American lexicon. It means someone of noble character. A ‘real mensch’ is an even greater compliment. It describes a person of rectitude, dignity and a sense of what is right.